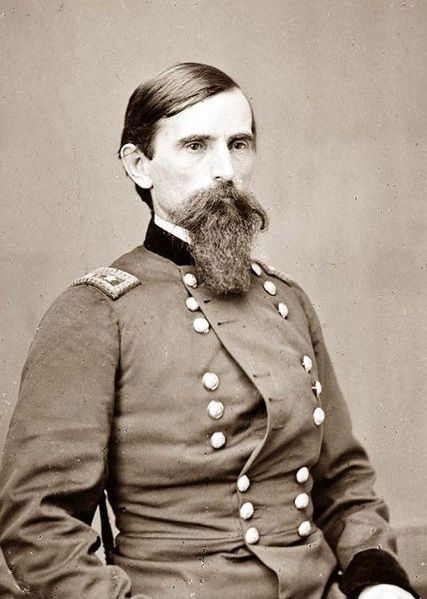

Favorite Historical Person: Lew Wallace

As I think about people I admire historically, a spectrum of Federal commanders come to mind: Winfield S. Hancock, Nelson Miles, John Gibbon, etc. But recently, I have come to steadily respect and admire more and more Lew Wallace.

As I think about people I admire historically, a spectrum of Federal commanders come to mind: Winfield S. Hancock, Nelson Miles, John Gibbon, etc. But recently, I have come to steadily respect and admire more and more Lew Wallace.

Wallace sits atop the mantle for a number of reasons. His tenacity, fearlessness in the face of overwhelming odds, and refusal to back down from half-truths are all traits that we can continue to draw inspiration from almost 155 years later.

His tenacity: When Wallace made a decision to do something, he never went at it half-hearted. He threw everything he had into an endeavor; on the battlefield that meant keeping control of his troops, and moving them to the best of his ability. Out of a warzone, as a budding writer, it meant re-examining perceptions if he realized they were wrong, and out of that doggedness came Ben-Hur, one of the America’s greatest novels.

Fearlessness in the face of overwhelming odds: Wallace is one of those people in history that honestly enjoyed combat. Serving as a young teenager in the waning years of the Mexican War, Wallace grew to love the martial lifestyle. With the onset of the Civil War, Wallace quickly put his services to the Union cause. Rising steadily through the ranks, Wallace’s star fell once he was scapegoated by Ulysses S. Grant and others for the battle of Shiloh (more on that below). Relegated to behind-the-lines details, Wallace once complained to his wife, “Soon will be heard the thunder of captains, the sound of the trumpet and the shout, and I not there.” He wanted action, no matter where it may be found. In that yearning for action, he oversaw the defense of Cincinnati in the fall of 1862, and finally, defended the banks of the Monocacy River. Though he had scant resources and faced a juggernaut of Confederate veterans, when asked to serve, Wallace rushed to the scene and fought an action that came to be known as the “The Battle that Saved Washington.” Though he didn’t have orders to do-so from higher officers, Wallace knew what had to be done, and rushed to action. Sometimes in life, we just have to do what’s right, and there isn’t time to ask for guidance, or permission. Wallace embodied that.

Refusal to back down from half-truths: I’m sure that at some point, most people have been the subject of rumors or slander. It’s frustrating, and more than that, infuriating if those rumors aren’t true. Wallace found himself in that position starting in 1862, and defended himself for the next 43 years, only being silenced when he died. At the battle of Shiloh, in April of 1862, Wallace marched his division across the bog of drenched and barely navigable roads around Pittsburg Landing. After the battle, Wallace was accused of being lost, and not following orders. The scapegoating started with Ulysses S. Grant, and Henry Halleck, and grew from there. But Wallace was never lost at Shiloh, and he followed orders he had received to the best of his ability. And so for the rest of his life he defended his actions, refusing to back down. That can equally be transmittable to the modern-day. When you’re in the right, and you know you’re in the right, say so, and keep saying so. Fortunately for Wallace, more and more historians are realizing that truth to the battle of Shiloh, and 112 years after his death, his truth is starting to emerge.

So I look up to Wallace, and I expect I will continue to do so.

An interesting article and some good points are made. Unfortunately Wallace overreacted to the Shiloh controversy and never let it go. Well after the war ended Grant finally acknowledged that Wallace had been wronged. But in the part of his autobiography which Wallace actually wrote c. 1903, he falsely claimed that on April 4, 1862 he had warned Grant of the imminent attack on Pittsburg Landing. All of the available evidence shows this to be absolute fiction. And then there’s the thorny question – after Wallace had headed down the wrong road (essentially not his fault) and was redirected, and despite being aware that the situation to the south was dire, he took the time to have the vanguard brigade counter march through the others, rather than simply facing everybody in the reverse direction and get the relief march underway then and there. .

I just finished reading a bio of General Charles Pomeroy Stone by Blaine Lamb. It seems that Wallace was not the only target of Grant . . . Just as Lee is getting his share of closer looks, Grant is as well. We must accept our generals, “warts and all.” Sometimes they were just wrong.

Also, the bio of Stone went into a lot of detail explaining the 19th-century military definition of honor. I think we have to stop saying that someone “overreacted” to something in this type of situation. In a recent bio of Gen. Gouverneur Warren, this was discussed as well. Both men were stung to the marrow of their bones by false accusations about their abilities and, even worse, their patriotism. In a day when our highest ranking military officers are relieved of duty and immediately become talking heads on news shows, it is difficult to imagine a different sensibility. We should try to do so more often, in my opinion.

“I think we have to stop saying that someone “overreacted” to something in this type of situation”

I respectfully disagree in the Wallace case. Grant finally (and properly) retracted the accusation against Wallace regarding taking the wrong road at Shiloh in a letter which was posthumously published in 1885. Wallace was vindicated. Yet nearly two decades letter Wallace published what was essentially a falsehood to the effect that he had warned Grant of the attack on April 4, 1862 – with the unavoidable (and calculated) implication to be inevitably drawn from the ensuing surprise on the morning of April 6. Persisting in the fight was bad enough. Doing it by creating a fiction was worse.

Hi John,

Thanks for reading and commenting. I absolutely agree with your comments about Wallace’s memoir. They have to be taken with an extreme grain of salt–in some parts they are more fiction than fact. I think Wallace took Grant down in his memoirs cause even though Grant had vindicated Wallace in the 1880s there were others who still believed Wallace was lost, and he defended himself by attacking Grant.

Ryan: That’s probably true. I’m not sure that Wallace thought out his fictional story about the alleged April 4 (or 3) “warning”. Even if you accept his version (which as noted is demonstrably false), he was subject to strong criticism for handling the transmission in the manner he said that he used. As we know, Wallace had only gotten into 1864 in his autobiography when he died. His widow and another finished it based on his papers. The fiction is largely confined to the first part. I also have yet to see any good explanation for his odd response once he was told that he was on the wrong road. Time was of the essence and he acted as if he were conducting a parade maneuver.

John,

I think Wallace’s movements once he found out he needed to turn around are also kind of confusing.

The explanation that I’ve heard regarding his counter-march is the fact that he wanted his more experienced troops from Ft. Donelson in front. Thus he had his entire division cycle through, as opposed to just turning around. The idea’s not half bad, but Wallace missed the bigger point: Grant needed people at Pittsburg Landing, it didn’t really matter if they were veterans or not.

Ryan: I agree that was his apparent reasoning but it was silly, especially given the circumstances, IMHO. Merely learning that had he continued on his original route he would now land in the midst of Johnston’s force (where Sherman previously had been located) was enough to signal that things were desperate on Grant’s end. Moreover, we’re talking about marching to get to a point – not deployment. The inherently subjective evaluation of which was the “best” brigade to place in the vanguard had to give way to the interests of speed – especially in light of the poor quality of the road Wallace would ultimately have to take to get to PL. His decision resulted in further delay and could not be justified from a military perspective. Yet that seems to have gotten lost in the vindication of his original decision/understanding regarding which route to take.

As I said–“warts & all.” I prefer my heroes off the pedestal. What is great is that we have all this primary source info, and we care about it. Both Wallace & Grant were human, therefore flawed. Gotta love it!

Flaws do not negate the strengths, in my opinion. .They just reflect the humanity of those who rose above at times in their lives.

It is worth mentioning that in addition to his martial credits, Lew Wallace was one of the nine members of the military commission that tried the Lincoln conspirators. After the trial, and when the defenders of Mary Surratt were impugning the integrity and the veracity of the testimony of one of the prosecutions star witnesses, Louis J. Weichmann, a boarder at Mary’s boarding house in Washington, it was Wallace, in addition to A. C. Richards, head of the Metropolitan Police, and Osborn H. Oldroyd, who came to Weichmann’s defense with the following statement:

I have never seen anything like his steadfastness. There he stood, a young man only twenty-three years of age. strikingly handsome, self-possessed, under the most searching cross-examination I have ever heard. He had been innocently involved in the schemes of the conspirators and although the Surratts were his personal friends, he was forced to appear and testify when subpoenaed. He realized deeply the sanctity of the oath he had taken to tell the truth , the whole truth and nothing but the truth, and his testimony could not be confused or shaken in the slightest detail.—Major General Lew Wallace

We gain some idea of the value of Wallace’s statement from the fact that on his deathbed, Weichmann swore that all the testimony he had given at the trial of the conspirators and at John Surratt’s trial was the absolute truth, and also from the fact that since 1865, despite calls for it, no evidence has been adduced in support of Mary’s innocence; on the contrary, all subsequent revelations further implicated her in the conspiracy to decapitate the United States government on the night of April 14, 1865.

Sorry but it was “Wrong Way Wallace”and he will always be remembered as “Wrong Way Wallace” He also had no integrity in defending the scoundrel Louis Weichmann and servicing on the kangaroo military commission. Weichmann was as guilty as the rest of them and everybody knew that! Stanton threatened him to turn as a state witness to make his case or he would have him hung with Mary Surratt! Also that doesn’t look good your on the commission that hangs the first women in American history! Nothing to be proud of there especially in those Victorian times! By writing Ben Hur that probably got him the museum in Indiana. Surely wasn’t what he did during his military career!

Thanks for the comment, Tim.

You can call him Wron Way Wallace, but there’s zero evidence he went the wrong way. This is what he spent the rest of his life defending. He used the road he and WHL Wallace had agreed to use in an emergency, and Grant’s orders never said to use the River Road.

To the military commission, there will always be debates about the Lincoln Conspirators, and that’s okay. Wallace thought Surratt was guilty, but he didn’t think she should be hanged, exactly for the reason you said. He was among the commissioners who sent a letter to President Johnson asking for clemency.

As to the military career, I think Monocacy speaks for itself.

Thanks again.

Tim:

Wallace a man of “no integrity”? Louis Weichmann a “scoundrel”? The “kangaroo military commission”? “Weichmann was as guilty as the rest of them and everybody knew that.”? “Stanton threatened him…”? Are we talking about the same people, time and place? Please consider;

1. Wallace’s opinion of Weichmann was echoed by A. C. Richards, head of the Metropolitan Police, and assassination historian Osborn H. Oldroyd, among many others. Weichmann was also thanked personally for his testimony by Tad Lincoln. His testimony was also confirmed by his deathbed statement, which, in law, is entitled to great weight as evidence, namely: “…every word I gave in evidence at the assassination trial is absolutely true.”

2. It was not Weichmann’s testimony that sent Mrs. Surratt to the gallows; it was John Lloyd’s, the tavern keeper in Surrattsville. Weichmann spoke highly of her and drew no conclusions from his testimony regarding her, leaving that to others.

3. John Surratt himself said that Weichmann was not part of the conspiracy, because he could neither ride a horse nor shoot a pistol.

4. Weichmann testified under oath that “no threats were made in case I did not divulge what I knew, and no offers or inducements if I did.”

5. The trial was not a farce. It was, rather, an enormous undertaking at an enormously difficult time under enormously difficult circumstances. It was carried out by conscientious and well-meaning men, competent, but nevertheless frail, like all of us. In the end, they acquitted themselves quite well, because, except in Spangler’s case, justice was served.

6. “Everybody knew that”? Apparently there were a lot of people who neither knew nor believed it. Hindsight is always 20-20. All generalizations are false. The credit belongs to the man who is in the arena, not to the man who points out how the strong man stumbled or how the doer of deeds might have done them better.

Thank you.

Ryan, Wallace didn’t show up where he was suppose to be and got reprimanded. He’ll have to live with that and for Monocacy, I have a different take for a battle I live just down the road from. Wallace was routed and reprimanded again. What saved Washington DC was the July heat and Confederate General Jubal Early’s fateful decision in the yard of the Blair Mansion on July 11,1864 not Wallace. If Early had attacked Wallace would probably been more severely scorned instead of saved by Grant.

John, I can’t write a dissertation here for a rebuttal because of the room here but to help you understand where I’m coming from. The military trial came about because Stanton wanted and needed to conviction and punishment of the conspirators as quick as possible. I agree with that but that doesn’t make it right because none of the conspirators were military combatants. Two years later when John Surratt was captured and put on trial they had a civilian trial. So if the original trial was wrong then it’s a farce and a trial that is a farce is run by a kangaroo court. I’m sorry you have so much invested in people and the trial itself, that still doesn’t make it right. As for Louis Weichmann, Mary Surratt was convicted because she took the package(field glasses) to John Lloyd on the 14th and for owning the boarding house where the conspirator’s met. Louis was with Mary in the carriage that went to the tavern and he was a boarder at the house where all the meeting were taking place with his best friend. If you don’t think he would have not been convicted had he not turned then you can’t have an honest conversation. Remember he didn’t turn John Surratt in after the failed kidnapping plot and then he goes immediately after the assassination to Montreal to find John because Stanton threatened him with prosecution. Also they needed a better witness than drunkard southern sympathizer John Lloyd who also turned to save his own neck (he aided and abided with the shooting irons and liquor). As for everybody thanking Louis after the trial, I would have thanked them for help in convicting the conspirators too. Again that doesn’t make it right. Lets get this straight, your defending a man who turned in his best friend and turned in his best friend’s mom who ends up getting hung just to save his own neck. Boy I’d watch it if I were your friend. On the gallows just before their hung it’s convicted brutal rascal Lew(is) Powell that showed more integrity and courage than Lew Wallace with his last words ” Mrs. Surratt is innocent. She doesn’t deserve to die with the rest of us!” He’s not thinking about himself but what could be more horrifying than hanging a woman in 1865!