John Bell Hood Ambushed at Devil’s River, Part 2

Emerging Civil War welcomes back Frank Jastrzembski.

(Part 2 of 2. You can find Part 1 here.)

The company discovered a source of clear water near the head of Devil’s River, south of Sonora. When the company moved to high range of mountains bordering Devil’s River, they spotted a few Indians at two miles distance on a ridge with a large white sheet flapping in the air. Before he left Fort Mason, Hood received word that a party of Tonkawa Indians was expected to be arriving at the reservation near Camp Cooper, and that they would raise a white flag as a sign to pass unmolested. This display made Hood uneasy, but he decided he had to oblige their peaceful gesture.

Hood galloped toward them to “ascertain the meaning of this demonstration.” Accompanying him were seventeen men while the rest of the men of Company G remained behind. He spaced his horsemen a few feet apart in a straight line, still mounted, as they moved forward at a slow trot “in readiness to talk or fight.” All of the men were likely armed with muzzle-loading Springfield M1847 musketoons – not the most reliable weapon – and each had a six-shooter strapped to his side or tucked into his waistline. A few lucky men carried sabers or two single-action Colt 1851 Navy revolvers; Hood sported a double barrel shotgun readied with buck shot and two Navy revolvers dangled from his side.

The cavalrymen approached to within 150-200 yards of the white flag, and Hood observed “a few Indians were lounging about with every appearance of a party desirous of peace.” The ground to the front formed a natural barrier of prickly Spanish bayonets. When the soldiers were within twenty or thirty paces of the Indians, four or five advanced holding the white flag; the one holding the nonaggression standard tossed it aside in a gesture of war.

It was a trap. The stillness was broken as the gunshots of the advancing Indians ripped through the air past the cavalrymen’s heads and horses. Hidden behind a mound of dry grass, thirty Indians stood, let out a high pitched yell, and began to open fire. Some of the bravest Indians even rushed up upon the cavalrymen and threw their weight behind their shields, ramming them into the heads and bodies of the cavalrymen’s horses.

Around the same time, a mounted party of Indians armed with lances emerged and charged Hood’s left flank. “The warriors were all painted, stripped to the waist, with either horns or wreaths of feathers upon their heads; they bore shields for defence, and were armed with rifles, bows and arrows,” Hood remembered. In total, about fifty Comanche and Lipan Apache Indians had fallen upon the seventeen men.

After discharging their muzzle loading musketoons in the initial volley, the soldiers drew their Navy revolvers out of their holsters and waistlines and fired at their attackers, some only a few feet away. The company fell back fifty yards and dismounted to reload their musketoons. The odds appeared desperate, leading Hood to remark, “But a miracle could effect [sic] our deliverance.” Hood’s men formed a makeshift perimeter, and drove back multiple attempts to overrun it forcing the Indians to seek shelter behind the smoke of the burning brush fires set by Indian squaws.

Hood stood roughly six-feet tall and had piercing blue eyes and a voice that roared even over the thunder of rifle fire, making him an ideal target. Suddenly, a well-directed arrow spun through the air and tore through the tissue of Hood’s left hand, pinning it to his bridle. John Bell Hood was not about to let this wound disable him. He decided to remove the arrow himself. “Unmindful of the fact that the feathers could not pass through the wound, I pulled the arrow in the direction in which it had been shot, and was compelled finally in order to free myself of it to seize the feathered in lieu of the barbed end,” Hood later explained.

A ghastly sound of “one continuous mourning howl” could be heard coming from the Indian squaws shielded behind the smoke of the fires. The Comanche and Lipan Apache Indians lost all taste for battle. This led to a cessation of the assault on Hood’s perimeter as they gathered their dead and wounded and moved off toward the Rio Grande. The American soldiers did not vacate their position until 10 p.m., fearful of another ambush.

The skirmish left Hood’s men severely dehydrated and physically exhausted. Hood ordered his cavalrymen to bivouac near a bank of Devil’s River after dark, and requested medical aid and supplies, sending out a messenger to Camp Hudson. “I attribute also our escape to the fact that the Indians did not have the self-possession to cut our bridle reins, which act would have proved fatal to us,” Hood afterward proclaimed. Lieutenant Theodore Fink arrived the next day with a detachment of infantry and returned to the site of the engagement to bury the bodies of Hood’s men.

Two of Hood’s men – Privates William Barry and Thomas Ryan – were killed, and four wounded (including Hood). It was a miracle he didn’t lose more. It was estimated that anywhere from nine to nineteen Indians were killed, and almost double wounded. Hood took Company G and traveled to Fort Clark to make a formal report of the affair. Captain Charles J. Whiting, with detachments of Companies C and K, pursued Hood’s assailants. They caught up with them on August 10 in the Wichita Mountains, and managed to kill two more of the party before they fled, capturing a large portion of their mules and horses.

Instead of censure for leading his men on the impulsive pursuit and into this trap, Hood received praise for his bravery and his ability to fend off the ambush. Brevet Major General David E. Twiggs, known for his own reckless bravery during the U.S.-Mexican War, was impressed with Hood’s performance during this encounter, stating in his report of August 5, 1857: “Lieutenant Hood’s affair was a most gallant one, and much credit is due to both the officer and men.” Another account indicated that Hood always armed half of his command with sabers, and the other half with revolvers after this encounter “thinking it best from his experiences in the affair, to be fully prepared for any similar emergency in the future.” If the company had been cut off and butchered –akin to Hood’s fellow West Point classmate Lieutenant John Lawrence Grattan and his command in 1854 – the response would have been quite different. It certainly helped his case that he held the field of battle after the affair and only suffered six casualties.

It is beyond doubt that Hood displayed exceptional bravery and leadership skills that made him legendary among the rank and file during the American Civil War. He had a knack for inspiring men to phenomenal feats. However, Hood’s poor judgment in pursuing the numerically superior Indian party over the desolate landscape impractically jeopardized the lives of his men. The ambush at Devil’s River was an indicator of his recklessness that became notorious during the later part of the American Civil War. Unfortunately, he was not commanding company-size formations and suffering the loss of a few men – over 6,000 would fall at Franklin owing to his rash orders – but instead ordered thousands of ill-fated Confederate soldiers to their deaths owing to his characteristic impulsiveness and lack of better judgment.

Further Reading

Brackett, Albert G. “The Battles of Nashville.” The United Service 13, no. 3 (September 1885): 257-263.

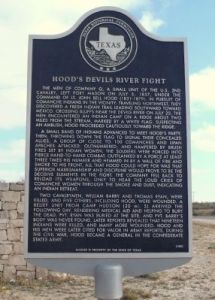

“Details for Hood’s Devils River Fight, Historical Marker – Atlas Number 5465002556.” Texas Historical Commission. http://atlas.thc.state.tx.us/Details/5465002556.

Girardi, Robert I. The Civil War Generals: Comrades, Peers, Rivals – In Their Own Words. Minneapolis, MN: Zenith Press, 2013.

Hood, John Bell. Advance and Retreat: Personal Experiences in the United States and Confederate States Armies. New Orleans: G. T. Beauregard, 1880.

Hood, Stephen M., ed. The Lost Papers of Confederate General John Bell Hood. El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2015.

Price, George F. Across the Continent with the Fifth Cavalry. New York: D. Van Nostrand, 1883.

Swift, Ebin. “The Pistol, the Mellay and the Fight at Devil’s River.” Journal of the United States Cavalry Association 24, no. 100 (January 1914): 554-566.

Welsh, Jack D. Medical Histories of Confederate Generals. Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1995.

Superb read. Please consider that Hood’s Army of Tennessee subordinates seldom obeyed his orders. Perhaps Hood took Frederick the Great ‘s advice -“L’audace, l’audace, toujours l’audace.”

Well, they followed his orders at Franklin and at Nashville. 🙂

About 60 miles west of Devils River, relics have been found that probably were taken off the bodies of the 2 dead soldiers.