Some General Thoughts on Major General George A. Custer

It is strange how often the passage of time tends to seemingly obscure our view of certain events. Such as that took place in southeastern Montana in the early summer of 1876. June 25 of our Centennial Year was a Sunday. On that Sabbath afternoon, Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer led the 7th U.S. Cavalry into the Valley of the Little Big Horn in pursuit of a village of Northern Plains Indians. For Custer and five of his companies, they were riding into the Valley of the Shadow of Death. That day, obscurity descended as the dust settled on top of that knoll where Custer and forty-two members of this battalion were found. One hundred and thirty-five years later, we still wish we could peer through the looking-glass and see what happened to Custer in the final two and half to three hours of his life. Although there are many theories, interpretations and ideas, we will never know. This is the one truth that continues to haunt us to this day and it is inescapable.

It is strange how often the passage of time tends to seemingly obscure our view of certain events. Such as that took place in southeastern Montana in the early summer of 1876. June 25 of our Centennial Year was a Sunday. On that Sabbath afternoon, Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer led the 7th U.S. Cavalry into the Valley of the Little Big Horn in pursuit of a village of Northern Plains Indians. For Custer and five of his companies, they were riding into the Valley of the Shadow of Death. That day, obscurity descended as the dust settled on top of that knoll where Custer and forty-two members of this battalion were found. One hundred and thirty-five years later, we still wish we could peer through the looking-glass and see what happened to Custer in the final two and half to three hours of his life. Although there are many theories, interpretations and ideas, we will never know. This is the one truth that continues to haunt us to this day and it is inescapable.

Stranger still is our view today of Custer so many years after his final battle. That fateful day, Custer divided his regiment three times in the face of a superior enemy; violating the concept of military science he had learned at West Point and had continued to study his entire adult life. Interestingly though, Robert E. Lee employed the same tactic thirteen years earlier at Chancellorsville and met tremendous success, his greatest victory. One might wonder what our perception today would be of Lee had “Fighting Joe” Hooker gotten the best of the Marble Man. It is even more difficult to comprehend how Custer could walk this Earth for 36 years but only be remembered for his actions in his closing days. What we also lose sight of on the Little Big Horn is the fact that Custer rose to fame-and the ranks of the U.S. Army-during arguably the most tragic chapter in our history.

Due to his tragic death, Custer was never able to complete his Civil War memoirs. He got as far as the Peninsula Campaign-Yorktown and Williamsburg to be precise-when he was serving as Staff Officer attached to the headquarters of various Union General Officers. Some may argue that Custer’s meteoric rise to Brigadier General was through the patronage of the two prominent Generals he served during the initial stages of the war, George McClellan and Alfred Pleasonton. However, this is not true. Custer literally had to pull himself up by the bootstraps to obtain the rank and leave an indelible impression on his superiors. During the Peninsula Campaign at the Siege of Yorktown, Custer ascended in an observation balloon to observe Confederate troop dispositions and movements. At Williamsburg, he accompanied Winfield Scott Hancock’s brigade and fought with the Fifth Wisconsin Infantry. Later on at New Bridge, Custer and a fellow staff officer fought a stiff engagement with the Confederates, effectively locating a fording point on the Chickahominy River. Altogether these actions earned the eye of George McClellan, who appointed Custer to his staff. Custer would remain with “Little Mac” until he was removed from command in November, 1862. Following a leave of absence, Custer returned to the Army of the Potomac after the disaster at Chancellorsville and found himself attached to the staff of Alfred Pleasonton. Like McClellan before him, the young officer idolized his chief. It was not long before Custer would be known as “Pleasonton’s Pet”, although it would not be long before Custer would prove his new-found devotion. In the middle of May, 1863 Custer accompanied a cavalry raiding column to the Northern Neck of Virginia. At Brandy Station, he accompanied Benjamin Davis’ brigade across Beverly Ford. Again in the Loudoun Valley at Aldie, he rode with the 1st Maine Cavalry in a charge that eventually turned the tide of the fighting.

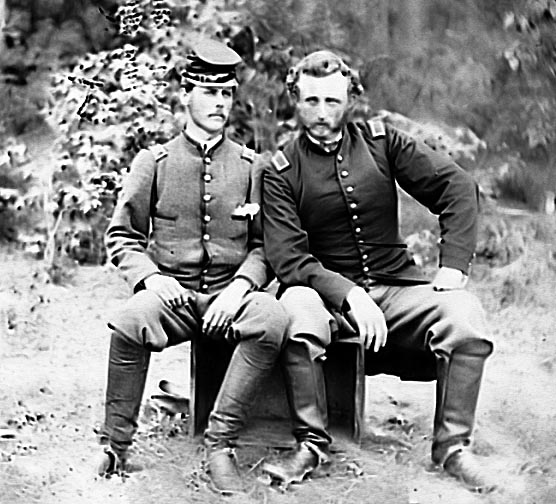

It was well deserved then when the Brevet Captain was promoted to Brigadier General to date from June 29, 1863. Custer’s first act as a General Officer to adopt his trademark, a distinctive uniform, something he would keep for the remainder of his life. His trousers had two thin single gold stripes on the seams. Custer’s coat was of black velvet, with two rows of gold buttons and five rows of looped gilt braid on the sleeves, with the lapels, collar and bottom trimmed in gold. Underneath his coat, he wore a sky blue sailor’s shirt that he had acquired during the Peninsula Campaign. A star was sewn on each collar, which was trimmed in white. Around his neck was a scarlet red cravat. He topped it off with a black hat that had a single gold star and gilt cord. Asked later why he had adopted such an unconventional appearance, Custer merely stated that he always wanted his men to know where he was in battle.

Custer was given command of four regiments of Michigan cavalry-the Michigan Brigade-and Battery M, 2d U.S. Artillery. He gained valuable experience leading his Wolverines through the remainder of 1863, and it was not long before he earned the respect of the men under his command. He later wrote to a friend regarding his new rank and responsibilities: “Often I think of the vast responsibility resting on me, in the many lives entrusted to my keeping, of the happiness of the so many households depending on my discretion and judgment and to think that I am just leaving my boyhood makes the responsibility appear greater. First be sure you’re right, then go ahead! I ask myself is it right? Satisfied that it is so, I let nothing swerve me from my purpose”.

That fall, he would adopt one of four personal guidons, a red over blue flag with white crossed sabers in the middle. Custer would also consolidate the musicians into one Brigade Band. The instrumentalists were never far from him on a battlefield. During the retreat down the Shenandoah Valley the following year when Custer’s troopers were fighting a rear guard action, James Taylor of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper remembered that Custer had his band out on the skirmish line playing “Yankee Doodle” and Custer’s personal favorite “Garryowen”.

The advent of 1864 once again brought change to the cavalry corps of the Army of the Potomac. During the earlier stages of the conflict, the Potomac Army’s horsemen had been viewed with derision not only by their Southern counterparts but by their Union comrades. It was not until the Cavalry units were consolidated in the winter of 1862-63 that the administrative and logistical changes began to take shape that these Horsemen began to perform to their full potential as a combat unit. Custer rose to command during this transformation and his actions helped to contribute to it. So much so that by the end of the year, the Union Cavalry in the East was a formidable force to reckon with. However, these strides would be offset with the appointment of Philip Sheridan as Corps Commander and Alfred Torbert and James Wilson as Division Commanders. Now, save for Division Commander David Gregg, three of the four high level commanders were inexperienced in commanding large bodies of mounted troops. This made the veteran brigade commanders, such as Custer, the backbone of the corps going into the spring campaign. Further, the fact that the Michigan Brigade was armed with Spencer 7 shot repeaters and was complimented with a battery of artillery, nearly guaranteed that Custer would be at the forefront of every action.

Custer’s experience in 1863 would pay off in 1864 and it was in this year that he would rise to National fame. Although he would play a small role in the opening battle of the campaign of the Wilderness, Custer and his Wolverines would distinguish themselves through the month of May. At Yellow Tavern on May 11, Custer would lead the assault that broke the Confederate lines. One of his privates is credited with mortally wounding the Confederate cavalry chief, J.E.B. Stuart. The next day, with the Cavalry Corps entangled and nearly trapped in Richmond’s Outer Defenses, Custer would open a way to safety during the fighting at Meadow Bridge. A couple of weeks later, the Wolverines would launch the decisive attack at Haw’s Shop and later be involved in the fighting around the crossroads of Cold Harbor. The only blemish on Custer’s record would be at Trevilian Station, where injudiciousness would get the Wolverines surrounded but fortunately they would be saved by Wesley Merritt and the U.S. Regulars.

With the main front in Virginia shifting to the Shenandoah Valley during the summer of 1864, Custer and his Wolverines would accompany Philip Sheridan and become part of the Army of the Shenandoah. On September 19, 1864 Custer would lead his Wolverines for the last time as their brigade commander at the Third Battle of Winchester. Along with the rest of the Division, Custer led his men into the Confederate rear and helped contribute to the Union victory. Later that month, James Wilson would be transferred to the William Tecumseh Sherman’s western Army, vacating the command post of the Third Cavalry Division. Sheridan promptly appointed Custer to Wilson’s vacated post. On the morning of October 9, Custer would lead his Division for the first time in battle. Never before had Custer commanded so many men on a battlefield. There was plenty of room to be apprehensive about how Custer would handle his men. At the Battle of Tom’s Brook, Custer turned in a brilliant performance, one worthy to be compared to John Buford’s handling of his Division on the first day at Gettysburg. On his front, Custer soundly defeated the Confederate cavalry. Ten days later, he distinguished himself in the closing battle of the campaign at Cedar Creek. For his actions, he was chosen to escort the captured Confederate battle flags to Washington to present to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton. During the presentation in Stanton’s office, the Secretary announced that Custer had been promoted to the rank of Brevet Major General.

The spring of 1865 would be decisive in Virginia. After wintering at Winchester, Custer opened the year by nearly annihilating the remnant of the Confederate Army that had opposed him the previous fall at Waynesboro, Virginia. He would lead his division in some of the closing battles of the war at Five Forks and Sayler’s Creek. It was Custer’s First Division who would cut off the Army of Northern Virginia’s escape route to the west at Appomattox. Not surprising then that Phil Sheridan commandeered the table on which Robert E. Lee signed the articles of surrender and sent it to Custer’s wife, Libbie.

George Custer emerged from the American Civil War as one of the most famous Cavalryman in North America. Obviously, Custer was a brave and courageous commander, but that is not what set him apart from his contemporaries. What made Custer a great commander was an appreciation for the psyche of the common citizen turned soldier. Part of this understanding was forged during Custer’s experience as a staff officer, where he was exposed to and fought with a variety of different regiments. When Custer took command of the Michigan Brigade, three of the four regiments had very little combat experience. The overall lack of experience, which Custer initially saw in his Wolverines as well as with the regiments he fought with early in 1862, motivates man’s natural fear of death during battle. But if soldiers see their commander, riding out in front of the line to lead them, exhibiting no fear, the realization comes that if the he is not afraid and willing to lead us then the fear turns to inspiration. This inspiration and the general idea was the driving factor to Custer’s success. Simply, it explains why Custer adopted such an odd uniform, a personal guidon and utilized a band, not only as a Brigade but as a Division commander. In turn, his men had a great confidence in him and it was reciprocated. Custer, without a doubt, believed, whether he was leading the Michigan Brigade or the Third Division, that his men could, no matter what the situation, achieve victory. Custer exuded self-confidence, which to those on the outside looking in can be mistaken as arrogance. Self confidence is a prerequisite for being a leader. Custer believed in himself and his abilities because to do otherwise would translate to the ranks he led and would ultimately lead to failure. James Kidd, an officer in the Sixth Michigan Cavalry, wrote to his father prior to the opening of the 1864 campaign: “Rumor says that General Custer may leave us. Bad luck to those who are instrumental in removing him. We swear by him. His name is our Battle Cry!”

George Custer emerged from the American Civil War as one of the most famous Cavalryman in North America. Obviously, Custer was a brave and courageous commander, but that is not what set him apart from his contemporaries. What made Custer a great commander was an appreciation for the psyche of the common citizen turned soldier. Part of this understanding was forged during Custer’s experience as a staff officer, where he was exposed to and fought with a variety of different regiments. When Custer took command of the Michigan Brigade, three of the four regiments had very little combat experience. The overall lack of experience, which Custer initially saw in his Wolverines as well as with the regiments he fought with early in 1862, motivates man’s natural fear of death during battle. But if soldiers see their commander, riding out in front of the line to lead them, exhibiting no fear, the realization comes that if the he is not afraid and willing to lead us then the fear turns to inspiration. This inspiration and the general idea was the driving factor to Custer’s success. Simply, it explains why Custer adopted such an odd uniform, a personal guidon and utilized a band, not only as a Brigade but as a Division commander. In turn, his men had a great confidence in him and it was reciprocated. Custer, without a doubt, believed, whether he was leading the Michigan Brigade or the Third Division, that his men could, no matter what the situation, achieve victory. Custer exuded self-confidence, which to those on the outside looking in can be mistaken as arrogance. Self confidence is a prerequisite for being a leader. Custer believed in himself and his abilities because to do otherwise would translate to the ranks he led and would ultimately lead to failure. James Kidd, an officer in the Sixth Michigan Cavalry, wrote to his father prior to the opening of the 1864 campaign: “Rumor says that General Custer may leave us. Bad luck to those who are instrumental in removing him. We swear by him. His name is our Battle Cry!”

Authored by Daniel T. Davis. © 2011 Emerging Civil War

Very well said, Daniel. I agree with pretty much everything you say.

As you probably know, I have done a great deal of work on the Michigan Cavalry Brigade, and was recently asked to edit another volume of letters, this time, by one of Custer’s staff officers. Consequently, I would venture to say that I have studied the exploits of the MCB as much as anyone, if not more so.

However, to get there, I had to overcome precisely the biases that you discuss in this post. Until my work on James H. Kidd’s writings forced me to reassess Custer, my perceptions of him were entirely tainted by how he met his end, and with very little focus on what he accomplished in the Civil War. It took the combination of reading Greg Urwin’s excellent Custer Victorious, my work on Kidd’s writings, and my work on Trevilian Station to come to the grudging conclusion that I was wrong, and it took a number of years for me to come to that conclusion. And I fought it every step of the way.

In my slow, grudging way, I’ve come to appreciate Custer for what he was: the embodiment of what a good hussar should be. He was fearless, he was bold, and most importantly, his leadership earned the respect, trust, and love of the men who followed his red necktie into battle. That the men of the MCB, and later, the Third Division, came to love him resonated with me. Surely there was a reason for that. And with that realization, my eyes opened.

I still firmly believe that he had many flaws, not the least of which was that his lack of experience at commanding anything smaller than a brigade created a great deal of trouble for him in the 7th Cavalry after the war. He was also a political naif, as demonstrated by his idealism in thinking he could take on Secretary of War Belknap without political consequences from the Grant Administration, and those consequences nearly ended his military career. To borrow a line from R. E. Lee, he was all of the lion and none of the fox.

And so, I came to respect George Custer. He will never be my favorite–John Buford and David Gregg always will be–but I no longer look at him as a bumbling fool who was reckless with the lives of his men. I know better.

And hopefully, after reading this post, your readers will too.

Keep up the good work. This was a great first post. As someone who’s made nearly 1100 blog posts over six years, I know how hard it can be to come up with fresh, interesting material, and I wish you well with doing so in the future.

Sir,

Thank you for the kind words. I am excited to see the staff officer’s letters that you mentioned when they are published. I really appreciate the work you have done on Farnsworth’s Charge. It is one of my favorite places to visit when I make the trip to Gettysburg. I don’t like to delve into too many “what if” scenarios, but I think Farnsworth’s death is precisely one of those. Of the three officers that Pleasonton recommends for promotion late in June, 1863, we will never know if Farnsworth would have lived up to the potential that his superiors recognized. I think Farnsworth was more than capable at that level of command; he handles himself well at Hanover and Hunterstown. It would have been interesting to see what he would have accomplished had he lived.

I agree, and as much as I like Custer, he did have his flaws. He was not a politically astute individual. There are some interesting studies concerning his leadership of the Seventh in particular, but I think there is much more there to be examined. There is definitely not enough room here to adequately cover it.

I have a tremendous amount of respect for John Buford and David Gregg. I don’t believe that Gregg has ever received his just due for the role that he played during the war. I think that he remains with the Army of the Potomac and does not go with Sheridan to the Valley simply because Grant and Meade cannot afford to give him up. Although he is solid throughout the brief period when he is in the field, Buford will always be remembered for his actions at Gettysburg. He truly turns in a sterling performance. It is almost as if he is passing the torch, so to speak. Buford provides a tactical blueprint for dismounted skirmishing at a time when grand mounted charges are becoming a thing of the past. In his actions, he sets forth an example for the younger, up and coming officers in the Cavalry Corps to follow, not only in 1863 but for the remainder of the war.

Daniel,

The letters that I will be working on were written by staff officer Edward Granger, who was KIA in 1864. The description of the Battle of Yellow Tavern left by Granger might well be the best one I have yet seen. The letters were compiled by a retired doctor who is related to Granger, but they desperately need to be annotated and to have connecting narrative written, and, on the recommendation of Prof. Greg Urwin, the publisher approached me. As it’s a university press (I can’t yet identify it), they’re still going through their academic rigamarole, but I think that’s nearly finished, and I am assured that the project will get a green light. This will be my fourth edited volume on the MCB.

Thank you for the kind words about my work on Farnsworth’s Charge. Interestingly, I am writing this while taking a break from the final review of the final page galleys of the new edition of my first book that will be going to the printer as soon as the index is done. Savas-Beatie is publishing it, and there is 15,000 words worth of new material in the main text, plus an additional 6000 about where the charge actually occurred. The new edition will be very different from the first.

John Buford has occupied my work for years. My first several articles on the Gettysburg Campaign featured him, and I am a great admirer of his. I have often said–and correctly, I think–that not only was John Buford the finest cavalry commander in the Union service, he also had the greatest influence. His legacy was in the form of his protege, Wesley Merritt, who served in the Regular Army for 43 years, commanded the Manila Expedition during the SpanAm War, and then retired as the army’s second ranking officer. Let’s remember that Merritt’s first company commander in the 2nd Dragoons in Utah–and the man from whom he learned the business of commanding cavalry–was Capt. John Buford.

I am likewise a great admirer of David Gregg’s. After the war, he settled in his wife’s hometown, Reading, PA, where he spent the rest of his life. Reading also happens to be my hometown. The handsome equestrian monument to General Gregg sits right across the street from the office of the doctor that I saw as a youth, and he was buried just up the street in Charles Evans Cemetery. There is a Gregg Street near my parents’ house, and the Gregg American Legion Post nearby. As a result, I’ve long admired the general, and hope that he will, someday soon, receive the recognition that he deserves. Nobody commanded a division in the AoP Cavalry Corps longer than did David Gregg, and that is all too often forgotten because Gregg was a quiet, modest fellow who didn’t seek attention from the press.

Eric

Eric,

I agree that Gregg is certainly an interesting character and largely under-recognized in the mainstream. A sharp tactical mind, with his laid-back aura (illustrated in his old photos where he often exudes a relaxed posture) makes for a unique contrast. I’ve always been a little unclear though as to why he hung up his spurs when he did. Any insight is much appreciated and keep up the great work.

Very cool. I will keep my eye out for the Granger letters in the future. I look forward to the next edition of Gettysburg’s Forgotten Cavalry Actions.

Thank you for this most interesting post! Not a long time ago I also didn’t realise that the real glory of this man comes from Civil War, not just from his final hours.

Very well thought out, and very entertainig as well. I loved reading this and it gave me a whole new insight to Custer.

Thank you all again for the kind words. To echo Kris, I’m looking forward to additional posts and discussions.

Daniel

Dayton,

Sadly, we don’t know for sure. His service file contains a letter of resignation that says that he wanted to return home to deal with pressing family business. It doesn’t say anything more than that.

Gregg was too much of a Victorian gentleman to elaborate, and never left anything in writing that is accessible to scholars to indicate the reasons why. Hence, we are left to speculate.

Dr. Alonzo Rockwell, the regimental surgeon of the 6th Ohio Cavalry, claimed that Gregg told him that his nerves were shot, and that that’s why he resigned. Rockwell suggests that Gregg was suffering from what we know today as PTSD. Personally, I don’t doubt that he might have been, but I SERIOUSLY doubt that was the reason for the resignation.

There’s much more here than meets the eye.

Gregg commanded a division in the AoP Cavalry Corps longer than anyone else, and it’s not a big stretch to imagine that he was miffed at being passed over for corps commander in favor of an infantry division commander with 60 days of experience in commanding cavalry in Sheridan. Then, Sheridan hung Gregg’s division out to dry at Samaria Church on June 24, 1864, and Gregg himself was lucky to escape capture. His command took better than 25% casualties that day, and I’m sure Gregg really resented that.

Then, he watched Sheridan fire and ruin the careers of his two friends and West Point classmates, William W. Averell and then A.T.A. Torbert, and I would guess that Gregg probably figured that he was next. He probably assumed that sooner or later, Sheridan would re-join the AoP at Petersburg, and I think he made up his mind that there was no way that he was going to serve under Sheridan again. That left him with two options: request a transfer or resign. So, he resigned because he probably figured at that late date there was no chance of a transfer.

It’s clear that Gregg later regretted that decision, as he later tried to obtain a commission as colonel of one of the new Regular Army cavalry regiments that were formed after the war, and those attempts were rebuffed by Grant. I suspect that Sheridan, who was a vindictive little bastard, told Grant that he wanted no part of an officer who resigned rather than serve under him, and that Grant went along with it. Gregg never got that commission.

We will never know for sure, but I’m pretty sure that my theory is as good of an explanation as we will ever get. It certainly is a plausible explanation.

I wonder what you think about my theory. Please feel free to share your thoughts with me.

I hope I’ve answered your question.

Eric

Eric,

Thank you for the informative response. You’ve shed a lot of light on this mystery for me, and your theory makes sense. The cumulative pressure of three years uninterrupted service in a hard-boiled military cauldron (PTSD), while attempting to survive the Sheridan career wrecking ball effect, would surely be too much for anybody to juggle. Perhaps something about him threatened Sheridan, or maybe it was just the political jockeying that was to blame (i.e. Averell, Torbert, and Warren).

I enjoyed reading of your early connection and interest to Reading and Gregg as a child. Sometimes I think the the eyes of youth can see and gauge more clearly than that of age and experience, and you obviously picked up on his significance early on – impressive that you were already ‘in tune’ with your present day interests back then.

For me, I read “Sheridan’s Lieutenants” a few years back, and for some reason Gregg always stood out of the bunch in an interesting way, considering the strength of his career and its puzzling end. I’ve since had the opportunity to visit some sites where he and his men did battle and have been humbled at the courage they displayed. In particular, I was amazed at how he seemingly kept his cool when it mattered most during ‘surprise’ encounters with the enemy at Aldie and Haw’s Shop. I cannot help but think it unfortunate that for someone so talented out in the field, it may very well be internal issues that prompted his early exit.

Could you recommend perhaps one of your titles, where I can do some more ‘digging’ on Gregg’s contributions? Thanks for keeping these guys in the conversation where they deserve to be and for your detailed response to my question.

-Dayton

Dayton,

I’m glad that that diatribe shed some light on the situation for you. Thanks for the kind words.

The two works of mine that deal with him most are my Trevilian Station study and also my book Protecting the Flank: The Battles for Brinkerhoff’s Ridge and East Cavalry Field, July 2-3, 1863. The latter is really focused on giving him his due for winning the fight on East Cavalry Field. However, I would wait to buy it if I were you. Savas-Beatie is going to do a new edition of it. In truth, it was supposed to be out next month, but Ted is way behind. I hope it will be out by the end of year. The new edition has a LOT of new material in it, as well as a new map.

At some point before I lay down my pen, I intend to write a bio of David Gregg.

Eric

Thank you for this valuable post. As a lay person, and Michigander, who has studied Custer, I am always glad to see his Civil War career emphasized. I have a question which may seem off-topic but hope you can shed some light. You mentioned the guidon he adopted. Many of us here in MI implored the Detroit Institute of Arts to donate the bloodied Little Bighorn guidon in their possession to a museum rather than auction it. Alas, it was auctioned by Sotheby’s for approximately one million dollars last December. (For those who aren’t familiar with this amazing artifact of the battle, please google “Culbertson guidon”). Do you happen to know who bought it? I have been searching relevant sites for months and can’t find a clue. Given the enormous interest in the LBH battle, it seems odd that the buyer has remained unknown. Many of us hope that it will be donated eventually to an appropriate museum. Thanks again for your post and any thoughts you may have on my question.

Oops–it sold for two million dollars. Sorry!

Daniel:

Excellent post. I can tell that you must have had a great undergraduate professor at Longwood who taught you everything that you know!!

You are absolutely right in that regard!!!

Unfortunately, I don’t have a good answer for you. I followed the sale of the guidon pretty closely and I don’t believe that the buyer’s name was ever made public by the auction company.

Drat…don’t you wonder where it is though? Above a mantle, in a bank vault…one of my friends thinks it will show up in an Indian casino (which wouldn’t be inappropriate since NA’s fought with him). I had a hope that Ted Turner bought it, given his interest in the CW and the West, and might donate it. Then again, it may be in Europe given their interest in Western artifacts. Oh well, thanks very much for taking the time to respond.

I agree, the guidon could be anywhere right now. No problem on responding, I will always respond to any questions posted on the blog to me.

Parenthetic note: the poor quality of Union cavalry before Custer and Merritt made their influence felt was reflected in a slur — “showing the yellow stripe” — which referred to the braid on the back of a Union cavalryman’s jacket. This was simpled down into “you’re yeller!” which was not originally a racial reference but was thought to be, and that’s probably why it’s only used in vintage Hollywood Westerns.

My comment–a year late! I now know Daniel, and Eric Wittenberg’s books grace my desk as I try to make sense of Custer’s actions at Gettysburg on the third day. I laughed out loud that Mr. W was not a Custer fan, and had to be led to the trough and encouraged to drink. I was in the same position–but my reading, my writing, and Daniel’s coaching through this paper for my Masters has made me, if not a full on fan, at least a begrudging admirer of Mr. C.

Truthfully, if I had read this a year ago, it would not have had nearly the impact it had this morning. I joined ECW in October, and it has been a gift. I truly think it is one of the best blogs out there. The variety and excellence of the writers is pretty much unparalleled. Huzzah!

To set the record straight. On 5 March 1866, David Gregg was recommended by Sheridan to appointment as a field grade officer in the cavalry. Sheridan praised Gregg as a “gallant and efficient officer” qualified for any position in the Cavalry. “The record of General Gregg is too well known to the (War) Department to require its mention by one”, Sheridan wrote. On 22 August 1866, U. S. Grant recommended David Gregg for appointment as a full colonel in the cavalry.

A fine, interesting account of a legendary warrior. Now just a small caveat, in the interest of preserving our wonderful English language and culture: a man can’t “literally pull himself up by his own bootstraps” without violating the laws of physics.