The Women of Winchester (part 3): Emma Riley Macon

We are happy to welcome back guest author Virginia Bensen. Part three in a series.

In the last article we discussed how the Unionist women reacted to the Confederate occupation during the first year of the Civil War. The discussion ended in December 1861. We will now skip over the winter months of 1862, and introduce you to Emma Riley, a teenage girl, and her adventure while trying to escape the Yankee invasion during the spring of 1862.

During February 1862, a scarlet fever epidemic broke out in Winchester. In March Emma’s mother, younger sister, and niece all died within three or four days of each other. Her mother passed on the Saturday before Jackson’s evacuation of the town. Chap Riley, Emma’s older brother who was a confederate soldier had serious concerns for the safety of Emma and her older sister Kate. He knew the Union troops were about to occupy Winchester. He also knew General Jackson was about to issue orders to evacuate the town at any moment, and he did not want to miss attending his mother’s funeral. The funeral was hurried and performed on Sunday, and Jackson’s Winchester evacuation occurred the next day, Monday. According to Emma, “We had never seen a Yankee in uniform then and imagined even women and children were unsafe in their hands.”

Emma and Kate Riley were told to pack only a few things as they would only be gone for a few days. Chad procured a small carriage and horses and drove the girls to a distant cousin’s house that was located further south and away from the Union army. After visiting there for a week, her brother found out that Jackson was falling back further south in the Shenandoah Valley, and the girls were then moved to Luray, Virginia. They stayed between two homes, that of Mrs. Jordan, and the other, Mr. John Lionberger. These were old family friends of the Rileys. Mr. Lionberger was an ardent Unionist, but his son who was nineteen joined the Confederate army. A quick aside, the son fell in love with Kate Riley. Mr. Lionberger also had a daughter who was in love with another Confederate officer, Captain Harris, who served in the same unit as the young Lionberger.

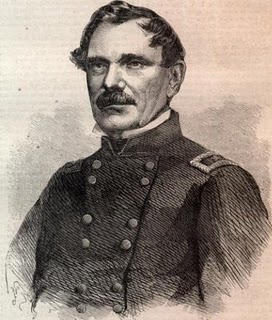

While staying in Luray, Virginia, Union General Shields occupied the town. He chose to establish his headquarters at Mrs. Jordan’s house, and Kate and Emma moved their things and stayed full-time at the Lionberger home. General Shields arrested all of the males in the town, and gave them a choice of taking the Oath of Allegiance to the United States government, or if they refused, going to prison. After enforcing the oath on the citizenry, General Shields left Luray to fight in Cross Keys and Port Republic. The town at this point was neither occupied by the Union nor the Confederates.

With the Union troops gone from Luray, John Lionberger, Jr. and Captain Harris, obtained leave passes by claiming to be sick. Both crept into Luray during the night and appeared at the Lionberger home to visit with their sweethearts, Kate Riley and Miss Lionberger. The girls wanted to see their beaus, but realizing the Yankees would probably return, and more importantly, they really did not wish the elder Lionberger to discover two men romancing his daughter and his family friend’s daughter inappropriately. The fact that Mr. Lionberger was a staunch Unionist somehow escaped the teenage minds. The girls and their beaus found a spot between the wall boards and the roof in the attic to hide the young men. In the meantime, the attic was extremely hot in the summer and cold in the winter and spring, so the lovers decided to occupy what was referred to as the spare bed chamber. If anyone inquired what was happening in that room, the men would hide under the bed, since the coverlet reached the floor. The girls smuggled food up to the room to feed the two men. Within a day, the Yankees had come back into Luray, and this time they stayed in town.

In the meantime one of the Lionberger servants went to the Union headquarters and reported that there were Confederates in their house. The Union soldiers searched the house twice, but could not find the two soldiers. The attic hiding place worked pretty well. An order was issued to continue searching every house in town until the two were found. To ensure that no escape would occur, sentinels were placed every fifty feet up and down the street of the Lionberger’s house. Needless to say, the two Confederates became rather anxious with the situation. How were they going to escape?

The three girls pooled some of their money and hired one of the citizens who had taken the oath, but he was really still loyal to the Confederates, to find colonel Harry Gilmore and his men who were hiding in the area, and ask him to rescue their two Confederate lovers. Not knowing if or when Gilmore would arrive, the couples planned an alternate escape. During the day, Emma and Miss Lionberger visited with another cousin who just happened to be staying in the house across the street, and that property adjoined where the town well was located. That evening after it became dark, Lionberger, Jr. put a women’s dress over his uniform and a sunbonnet on his head. He and two of the girls went out to the town well which was across the street under the guise of getting water. When at the well, he exchanged places with his sister. Captain Harris remained hidden in the attic. Lionberger, Jr. and the girls were going to repeat the “put on a dress and go to the well ploy” that next evening with Captain Harris.

About mid-morning of the next day, as the Union troops were searching the house next door to the Lionbergers, everyone heard the loud Rebel Yell, and Colonel Gilmore appeared with his men. The Union soldiers scattered to the other side of town. Lionberger, Jr. and Captain Harris came running, jumped upon the back of two horses that Gilmore provided, and escaped. The Union troops quickly caught on as to the purpose of the Gilmore raid.

As the girls were jumping up and down in excitement over their lovers’ escape, the Union troops appeared with a notice for Mr. Lionberger and his family to evacuate his house. It was to be burned as punishment for treason, and the Lionberger family was to be sent into enemy lines. Mr. Lionberger became frantic, because he had no idea what had just happened. After all, he had taken the oath and was loyal to the Union. He went to the General’s headquarters and pleaded. The girls decided that they had better confess to what had just happened. After hours at headquarters, the General finally rescinded his order and the Lionberger house was spared.

This story shows that teenagers have not changed much in the past 150 years. Can you imagine Mr. Lionberger’s response as the girl’s explained their actions to General Shields? And, can you imagine his reaction to the girls after all had returned to his home? Emma Riley conveniently left that part out of her recollection of events.

A brief aside….while I was preparing this article, I read Kris White’s posting about “Extra Billy.” In Emma Riley Macon’s Reminiscences of the Civil War, I found a reference to “Extra Billy.” After the Battle of Antietam many of the Confederate wounded were transported to Winchester, Virginia, and many recuperated in local homes. One of those homes was Emma’s.

Here is the excerpt:

Our house soon filled up with wounded from that battle. Two were in each vacant room, among them General Smith, better known in Virginia’s history as “Extra Billy,” and three times governor of Virginia. His companion was Colonel Catlett Gilson, an officer in his brigade. We found out later that they were not on speaking terms but by accident had been put in the same ambulance when wounded and sent to our house, and there they remained for weeks without ever exchanging a word.

Imagine what a cheerful time they must have had, especially in the “wee sma’ hours” of the night, both suffering agony from wounds and neither exchanging a word of sympathy for the other. If they had been women, I bet they would have broken the silence at any cost. (Emma Riley Macon, Reminiscences of the Civil War, 31.)

Macon, Emma Cassandra Riley Manuscript, “Reminiscences of the Civil War, 1861-1865.

enjoyed this article much. loved the commercial at the end even better. goid bless that man.

Virginia, Would you be interested in a virtual tour of the places that you mention around Luray? I can post a supplemental post telling more about the places, as well as the people that you mention.

Robert

http://cenantua.wordpress.com/

http://avenueofarmies.wordpress.com/about/

Virginia, A colleague and friend pointed this blog out to me and I want to thank you for sharing just one of many great stories about Emma’s life as a teenager in Winchester during the Civil War. She is my great grandmother and my mother showed me her book when I was 13 and I did the same for my 2 daughters when they turned 13. It had a profound influence on my life and was one reason why I spent my career working in history museums. Thank you for bringing her story back to life.

It would be nice if you spelled Emma’s name correctly: RIELY.