Prelude to a Star: The Battle of Aldie

Part four in a series.

The dilapidated buildings greeted the young officer. George Custer was quite familiar with the area around Catlett’s Station, a rail stop on the Orange and Alexandria Railroad. Here, the previous March, Custer had led his first cavalry charge against an enemy rearguard that was covering the Confederate retreat from Manassas. Then, Custer was assigned to the 5th U.S. Cavalry. Now, he was serving on the staff of Alfred Pleasonton, the commander of the Army of the Potomac’s cavalry corps. That morning, the cavalry was on the move.

While the Battle of Brandy Station flexed the muscle of the Union Cavalry, it did not hinder the movement of the Army of Northern Virginia in Robert E. Lee’s second invasion of the Northern states. Despite the fact that Pleasonton, had kept his troopers in relatively close proximity to the Confederates following the battle, he had very little solid intelligence concerning Lee’s movements to pass on to the commander of the Army of the Potomac, Joseph Hooker. Although Pleasonton would forward several different reports to Army headquarters in the days after Brandy Station, it was not enough to convince Hooker that Lee’s Infantry remained opposite his own lines at Fredericksburg. Thus on June 14, Hooker began withdrawing the Potomac Army away from the Rappahannock River and moving northward to concentrate on the Orange and Alexandria Railroad between Centreville and Catlett’s Station.

Meanwhile, the Army of Northern Virginia was indeed on the move. On June 13, Lee’s Second Corps reached Winchester in the lower Shenandoah Valley. As Lee moved west and then north, J.E.B. Stuart and his Confederate horsemen spread out east of the Blue Ridge Mountains to screen the advance of the infantry. To successfully complete this mission, Stuart would have to maintain a tight hold on two roads that ran from the mountains toward Manassas and Hooker’s army: the Little River Turnpike (modern Route 50) and the Snickersville Turnpike (modern Route 734). Each of these roads led to mountain passes and the main body of the Confederate army. Further, these roads intersected well east of the mountains in the small town of Aldie, giving it a strategic importance to Stuart.

Finally fed up with overall lack of verifiable intelligence, Pleasonton received his orders on the morning of 17 June. Custer may very well have been the one to initially receive the orders at headquarters before giving them to Pleasonton. In part they read “The Commanding General relies upon you with your cavalry force to give him information of where the enemy is, his force, and his movements. You have a sufficient cavalry force to do this. Drive in pickets, if necessary and get us information. It is better that we should lose men than to be without knowledge of the enemy.” After receiving the communication, Pleasonton decided to send Major General David Gregg to Aldie. Custer drew the assignment riding with Gregg.

Leading off the advance of Gregg’s Division was the four regiments of Judson Kilpatrick’s brigade, the 1st Massachusetts, 2d and 4th New York and the 6th Ohio. Kilpatrick would be accompanied by Alanson Randol’s combined Batteries E and G, 1st U.S. Artillery. Marching east at almost the same time came the brigade of Thomas Munford, consisting of the 1st, 2d, 3d, 4th, and 5th Virginia Regiments. Like his counterpart, Munford also had the added luxury of being supported by James Breathed’s Battery of Horse Artillery.

Aldie would be a meeting engagement, meaning that neither side expected to find one another. Around 2:30 on the afternoon of June 17, 1863 elements of the 2d New York ran into pickets from the 2d Virginia Cavalry just east of town. Utilizing their numbers, the New Yorkers pushed the Virginians back through the town to the west, only to run up against the 5th Virginia under the command of Thomas Rosser. In turn, Rosser ordered his men into the fight and pushed the 2d New York back into the town. Rosser then directed his regiment to some high ground west of Aldie. This withdrawal allowed Kilpatrick time to bring up the rest of his brigade as well as to deploy Randol’s Battery on a high knoll near the Snickersville Turnpike. Deploying his regiments in order of the line of march as they arrived, the 6th Ohio joined the 2d New York on the Little River Turnpike. The 4th New York came on line to support both Randol’s guns and the 1st Massachusetts Cavalry.

Custer rode with Gregg along the Little River Turnpike as the Union troopers pushed through the village. He was wearing a straw hat for protection from the sun. An observer remembered that Custer was “dressed like an ordinary enlisted man, his trousers tucked in a pair of short legged government boots, his horse equipments being those of an ordinary wagonmaster”. As he reached the Little River, Custer crossed to the other side to water his horse. After drinking, Custer nudged his horse to return to the opposite bank. Moving up the bank, the horse slipped, sending Custer into the river. Although soaking wet, miraculously, Custer was not hurt.

Gregg soon set up his command on the same knoll where Randol’s guns were deployed. Alongside Gregg, Custer watched as Kilpatrick’s troopers dislodged the 5th Virginia from their position west of the town. Suddenly, pickets from the 2d Virginia appeared along the Snickersville Turnpike.

With the fighting winding down on the Little River Turnpike, the sphere of combat would shift to the Snickersville Pike between the remainder of Kilpatrick’s and Munford’s Brigades. Moving against Munford was the 1st Massachusetts and the 4th New York. The attacks were made piece meal. Both regiments would break themselves attacking the Confederates, who were fighting dismounted behind a stonewall and with artillery support.

With their attacks spent, Munford decided to counterattack and sent forward Colonel Thomas Owen’s 3d Virginia. This attack came at a critical moment in the battle. There were no immediate Union reinforcements at hand and the road was open for Owen’s Virginians to advance and capture not only Randol’s Battery, but the vital intersection of the Turnpikes. Luck would have it that the lead element of J. Irvin Gregg’s brigade were now coming onto the field in the form of the Calvin Douty’s 1st Maine Cavalry. Spotting Douty’s Regiment, Kilpatrick ordered them to deploy and save Randol’s guns. Kilpatrick himself would order Douty forward.

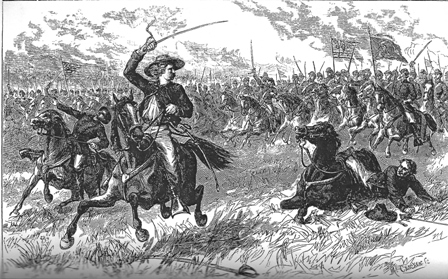

Recognizing the critical moment was at hand, Custer joined Douty at the head of the regiment as the Colonel ordered the charge. The men from Maine hit the Virginians and steadily drove them back to their original position. Douty was killed during the attack, but his last effort helped secure the key intersection for David Gregg. By this time, darkness was ascending and the two sides began to disengage. In a sense, it would also be Custer’s last charge.

You mentioned four regiments that Kilpatrick lead at Aldie. However, you left out the 1st Maine and the 1st Rhode Island. You also mentioned Maine in your article

The 1st Rhode Island wasn’t at the battle, they were on detached duty in Middleburg. The 1st Maine was part of J. Irvin Gregg’s brigade. The 1st Maine was ordered onto the field by Pleasonton to support the artillery and Kilpatrick put them to use.