A General Redeemed: Lew Wallace and the Battle of Monocacy

A guest post by Ryan Quint, part two of a series.

Saturday, July 9th, 1864, came following a night of thunderous rain and lightning showers. The first rays of sunlight poked over the nearby mountains and revealed two armies poised for combat.

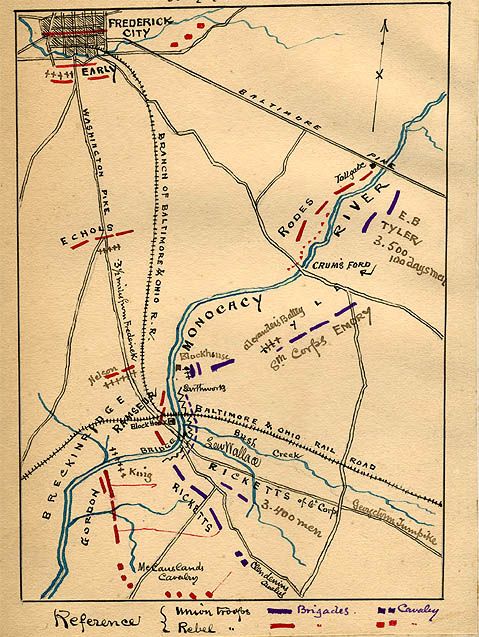

Major General Lew Wallace, 34, had come to the Monocacy Junction four days earlier, on July 5th. He arrived with a small force of inexperienced soldiers belonging to his 8th Corps. Marching straight at him were about 14,000 Confederates under the command of Jubal Early. Early’s objective: The capital of Washington D.C., only about 40 miles behind Wallace from his current position by Frederick, Maryland.

Wallace had been sent some help from the Army of the Potomac; the Third Division of the Sixth Corps, under the command of Brigadier General James Ricketts. Ricketts was just the man needed at the Junction- he had seen combat throughout the first half of the war and had been through the Overland Campaign. His veterans filed to the south of Wallace’s line throughout the early morning hours of July 9th.

As he awoke, Lew Wallace must have peered over the situation before him from his headquarters on the eastern side of the Monocacy River. Before him was the bending river that dipped and slipped its way through the fertile Maryland countryside. All around Wallace were fields of wheat and corn, ready for harvesting. About three miles to his front was the city of Frederick, where the Confederate Army of the Valley had bivouacked the previous night.

Credit: Monocacy NPS

Wallace had a strength of approximately 7,500 soldiers, with 2,500 of them being his inexperienced 100-day men. The rest were under Ricketts, located in three brigades, but only two of his brigades would fight on the 9th.[i] For a longer arm of service, Wallace could rely on the six rifled guns of Frederick Alexander’s Baltimore Battery, plus two howitzers. One of the howitzers was positioned by a blockhouse next to the junction, and the second was a smaller mountain gun that had been brought up at the last-minute.[ii]

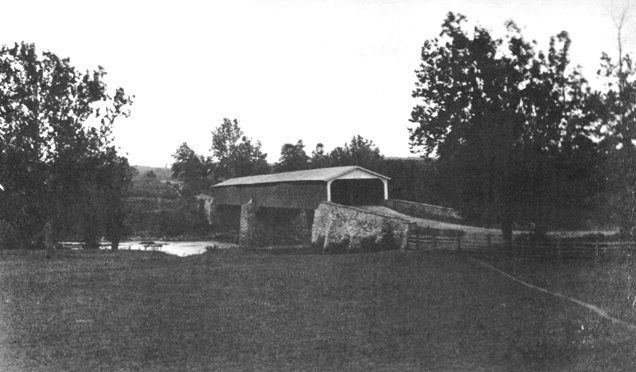

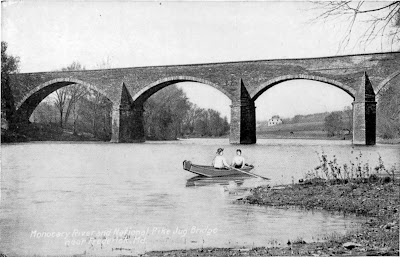

Crossing the Monocacy were three bridges that Wallace needed to protect during the coming battle. On his right flank was the stone bridge that carried the Baltimore Pike across the Monocacy River. In his center Wallace had the iron railroad bridge that he had come to defend in the first place, answering the pleas of a Baltimore & Ohio R.R. executive. The railroad ties met at a junction on the western side of the river, and then crossed the Monocacy on their way to Washington. Finally, about 300 yards south of the railroad crossing was a wooden covered bridge that spanned the river and carried the macadamized Georgetown Pike back towards the capital city.[iii]

The three bridges were the access points that Wallace would need to protect. His northern flank, the stone bridge, led back to his headquarters in Baltimore, while the covered bridge went to Washington, the city that at that very moment was descending into chaos because of the rebels’ invasion. It would be up to Lew Wallace to protect the Monocacy bridges. He assigned Brig. Gen Erastus Tyler, a crusty veteran of the Battle of Fredericksburg, to defend the stone bridge. Wallace succinctly stated, “Upon the holding of that bridge depended the security of my right flank, and the line of retreat to Baltimore.”[iv]

To guard the covered bridge and the vital railroad junction, Wallace looked at the recent-arrivals of the Sixth Corps. Ricketts’ men aligned themselves “in two lines across the Washington pike, so as to hold the rising ground south of it and the wooden bridge across the river.”[v] Skirmishers were posted across the Monocacy, taking cover near the junction itself. With his limited artillery, Wallace had the howitzers hold their position near the blockhouses, and then he divided Alexander’s battery so that Tyler and Ricketts both received three of the 3-inch Rifles. With Wallace’s limited force posted, the Indiana native could do nothing but wait for Jubal Early’s Confederates.[vi]

The Battle of Monocacy began around 6 a.m., as Confederates moved down the Baltimore Pike. Skirmishing broke out around the stone bridge, and then intensified by 8 in the morning as other rebels moved against the Sixth Corps skirmishers at the junction. Alexander’s battery soon had their hands full, as, by Captain Alexander’s count, Early’s men “brought, as nearly as I can judge, about sixteen guns to bear on us…”[vii]

Credit: Ryan Quint

Skirmishing was all the battle amounted to until around 10:30 in the morning, when Confederate cavalry tried to outflank Wallace’s line. They splashed across the Monocacy River at a ford and dismounted in the front yard of the Worthington House, whose windows had been boarded up in the face of the inevitable battle. From one of the cracks of the windows stared six year old Glenn Worthington, who, in time, would become the battle’s first historian.[viii]

According to Lew Wallace, in his memoirs written in the early 1900s, he warned Ricketts of the impending cavalry assault. He wrote to Ricketts, “A line of skirmishers is advancing… at your left. I suggest you change front in that direction…”[ix] Whether or not Wallace was as gentle in his orders as his memoirs portrayed, Ricketts soon had his brigades maneuvering towards the Confederate troopers. The Sixth Corps men knelt down behind a fence post, hidden by a cornfield that easily concealed them in its harvesting stage.

The first indication that the rebels had of troops to their front was the Federals standing, leveling their rifles at 125 yards, and firing a withering volley into their ranks. As the smoke cleared, the Confederates who had not been struck down were retreating back towards the Worthington Farm.[x]

For Lew Wallace, everything was going as well as could be expected. His small force was delaying the rebels in front of them splendidly. It was closing in on noon, and his men still had plenty of fight left in them. Every hour they held was one more that Washington D.C., had to prepare and one less that Early had to use in marching towards the city. But even as his men held on, Wallace could do little as the Confederates brought up more and more men to push against his lines. More rebel batteries unlimbered in the farms across the Monocacy and began to shell the Union lines. The Federals guarding the covered bridge were needed on the left, by the Worthington Farm, as the Confederate cavalry was joined by infantry and prepared to attack again. So with little else to do, Wallace ordered the bridge burned.[xi] Soon dark black clouds of smoke were rolling up towards the cloudless sky and bright flames lapped at the bridge’s wooden planks.

Credit: Monocacy NPS

As Wallace shifted men to the increasingly threatened left, the Confederate cavalry attacked again. This time the gray-clad men shifted around the high corn and thus avoided the deadly skirmishers. They came on with full force, while behind them the Confederate infantry prepared for their own assault. The Confederate troopers ran headlong into the Federal lines around the Thomas House, which Wallace described as “a stately mansion house.”[xii]

The fields around the Thomas House quickly descended into chaos. As Ricketts and other commanders responded to the Confederate cavalry, musketry cracked and thick clouds of smoke covered the combatants. Rebel artillery, moved up to support the dismounted troopers, sent shells crashing through the house and damaging it thoroughly. Glenn Worthington later described the fighting as, “It was load and fire, load and fire: Kill, kill, kill….”[xiii]

For a short time, the Confederate troopers managed to hold onto the Thomas House. But as Federal regiments rushed up from the now engulfed bridge, Wallace’s men were able to recapture the house and push the Confederates back a second time to the Worthington Farm. As they stood around their trophy, the Federals had barely enough time to stabilize their lines and prepare for the zenith of the Confederate attack.

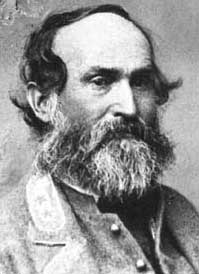

It was now 3:30 in the afternoon, and Lew Wallace had done more than could be expected of him. With a small force, almost half of them inexperienced soldiers whom no one expected to fight, he had delayed some of the Confederacy’s best shock troops. But now Wallace had to contend with Major General John B. Gordon, who during the Overland Campaign had quickly risen to one of the Army of Northern Virginia’s best commanders.[xiv]

Gordon’s three brigades included the remnants of the Stonewall Brigade, the Louisiana Tigers, and likeminded soldiers who had long ago earned their place in Confederate lore. Now they advanced towards Wallace’s already tired line. In his memoirs, Gordon wrote, “As we reached the first line of strong and high fencing, and my men began to climb over it, they were met by a tempest of bullets, and many of the brave fellows fell at the first volley.”[xv]

Wallace’s men had been fighting all day; their ammunition was running low, casualties in Ricketts’ brigades were increasing, and though they shot Gordon’s men down in droves, the rested and adrenaline-filled rebels pushed on. Gordon’s three brigades were fronted with crack sharpshooter battalions that shot down the Federals as they struggled again in the already bloodied fields about the Thomas House.[xvi]

Shortly after Gordon’s division began its last assault on the Federal line, Wallace looked to the Baltimore Pike. He had held on for the entire day, and now it was time to retreat. He would have to give the Confederates to the road to Washington and hope that the capital had used the time he gave them.

It was shortly after 4:30 in the evening when Wallace’s weary men began to retreat north away from the Thomas House and towards the Baltimore Pike. The general was worried of disengaging the rebels, a tricky situation under any circumstances. But “it was a thing of execution by veterans, and the reflection made me several degrees more hopeful.”[xvii]

The Battle of Monocacy, for having comparatively small forces engaged, was extremely bloody. Wallace brought about 8,000 men into action, and lost almost 2,000 of them along the banks of the Monocacy. Early’s forces, numbered around 14,000 at Monocacy, suffered about 1,150 to Wallace’s men.[xviii]

As the sun set in the distance, the Federals moved onto the Baltimore Pike. They were bloodied, they were powder-grimed, they were tired, and they were beaten. However, as the men under Lew Wallace began their retreat towards Baltimore, Jubal Early could do nothing but halt for the rest of the day to care for the dead and wounded at Monocacy. As Wallace would later note “If the day was lost to me, General Early might not profit from it.” The general who had been disgraced at Shiloh and shunned to a backwater department had now been redeemed. He had saved the capital; just no one knew it yet.

Part 3 will look at the aftermath of the Battle of Monocacy, its importance in Early’s 1864 invasion, and Wallace’s post-war career.

Two quick corrections. In Part One, I typed “Wallace’s men began to skirmish with Jubal Early’s vanguard across the Monocacy at nearby Frederick on July 8th…” This was a typo; the skirmishing outside of Frederick began on the 7th, not the 8th. Secondly, I said, “With nightfall [of the 8th], though, came reinforcements.” This was a mistake on my part- Ricketts’ Third Division arrived early in the morning of the 9th, not late on the 8th.

[i] Glenn H. Worthington, Fighting for Time: The Battle of Monocacy (White Mane Publishing, 1985 reprint) 87. Ricketts’ third brigade stayed about 8 miles away from the fight for reasons that are beyond this post.

[ii] B. Franklin Cooling, Monocacy: The Battle that Saved Washington (White Mane Publishing, 2000) 252.

[iii] Worthington, 57. The covered bridge had been burned by Confederates during the Antietam Campaign and subsequently rebuilt; Edwin C. Bearss, The Battle of Monocacy: A Documented Report (NPS, 2002), 13.

[iv] Wallace’s Report, The Official Records of the War of the Rebellion (U.S. War Department, 128 volumes), Ser. 1, Volume 37, pt. 1, 196. Hereafter cited as OR.

[v] Ibid.

[vi] Alexander’s Report, OR, Ser. I, Volume 37, pt. 1, 223.

[vii] Ibid., 224.

[viii] Worthington, 118; Cooling, Monocacy, 142.

[ix] Lew Wallace, An Autobiography: Volume II (Harper and Brothers, 1906) 766.

[x] Marc Leepson, Desperate Engagement: How a little-known Civil War Battle Saved Washington D.C., and changed the course of America Hustory (Thomas Dunne Books, 2007) 104.

[xi] Bearss, 37.

[xii] Wallace, Autobiography: Volume II, 713.

[xiii] Worthington, 124-125.

[xiv] Leepson, 111.

[xv] John B. Gordon, Reminisces of the Civil War (Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1904) 311.

[xvi] Fred L. Ray, Shock Troops of the Confederacy: The Sharpshooter Battalions of the Army of Northern Virginia (CFS Press, 2006) 154.

[xvii] Wallace, Autobiography: Volume II, 786.

[xviii] Cooling, Monocacy, 250, 252.

Good article. I’ve always wondered why, during the US Civil War, cavalry was only utilized in the role of mounted infantry. This applies on both sides. Ever since the time of Frederick the Great, Western armies knew the danger of having cavalry engage in a direct, head-long charge against a line of musket-bearing infantry. Even when facing rifle-bearing skirmishers, such as Hessian, Prussian or Austrian Jaegers, most European cavalry would choose to flank such infantry or utilize terrain in such a way so as to minimize the range of said firepower. During the Franco-Prussian War, which happened a few years after the US Civil War, the Prussians and their German allies successfully employed heavy cavalry and even lancers and hussars against the heavily armed armies of the Second French Empire. Some say the US and CSA used cavalry in the manner of “mobile infantry” purely because they didn’t have the funds or intent, prior to 1861, to mobilize and maintain a large peacetime cavalry force. The argument is that we didn’t feel we needed one, due to the nature of our foes and the nature of the strategic threats facing the nation prior to civil war. I’d be interested in your take on the subject.

Thanks for reading and replying. As far as the usage of cavalry during the Civil War; prior to Joseph Hooker’s command of the Army of the Potomac, Federal cavalry in the eastern theater was not even really used as mobile infantry. It was much more common to see cavalry squadrons utilized as scouts or guarding wagon trains, etc. Hooker took the army’s cavalry, put them into a single corps, and began to use them as a hard hitting force; see Kelly’s Ford and Brandy Station. When it comes to how Europeans utilized cavalry vs how their American counterparts did, I think a look at topography is important; battles where heavy cavalry was utilized before or after the Civil War included wide open fields, while during the Civil War was fought on the North American continent, a much heavier wooded area. To see the folly of using cavalry in such bad terrain, see Kilpatrick’s men at the base of Little Round Top on July 3rd at Gettysburg. By 1864, the Federal cavalry was armed with rapid-fire carbines, like the Spencer, so it made sense to dismount them as mobile infantry and just blast away. Phil Sheridan’s cavalry was able to repulse Confederate infantry at Cold Harbor by digging in and then firing with his Spencers. To return to Monocacy, Early tried to utilize his cavalry as mobile and dismounted because they were fast-striking and could get into position before his infantry could deploy; his troopers, under McCausland, were beaten because Ricketts’ skirmishers were in a better position and had better fields of fire.

Ryan, where is part three of your article on Lew Wallace and the Battle of the Monocacy?

Peter, thank you for your interest. I am currently writing the third and final part on Lew Wallace. It is taking a little longer than I thought it would, and I apologize. School work tends to get in the way of the more fun things I’d like to be doing, such as these writings.

I had a relative in the 11th Md. I would like to know if any of them were wounded. I don’t believe they had any fatalities.