Swapped Identities: Battle of Bristoe Station, October 14, 1863

If Gettysburg is to be considered the turning point of the Civil War in the east, then Bristoe Station is the manifestation of the changes experienced by the Army of the Potomac and Army of Northern Virginia. Accounts of this October 14, 1863 engagement near Manassas Junction, Virginia appear as if the two armies have switched uniforms—each borrowing traits and mistakes the other previously displayed on the battlefield. The Confederate army showed difficulty adapting to a new identity necessitated by high casualties among its officers and enlisted men while the Union displayed a reinvigorated fighting spirit—when properly led—that was to be tested with Ulysses S. Grant’s arrival in 1864 and the commencement of the Overland Campaign.

Following the July 1863 invasion into Pennsylvania, Robert E. Lee and George G. Meade warily eyed each other in the Virginia Piedmont. The Union commander continuously delayed pressure from Washington to follow up the summer success, citing his drained resources from shipping the XI and XII Corps out west. Lee sought to take advantage of the inactivity by borrowing a page out of his playbook from 1862. Just as in the campaign that culminated at Second Manassas, circuitous marching routes could potentially position his forces between the Union army and their capital, pinning them up against the lateral rivers that defined the region.

But Meade would not play the “miscreant that needs suppressed” role the way John Pope did in August 1862 and began gathering his army towards the strong defenses leading into Washington. Though vulnerable strung out in a long withdrawal centered along the Orange & Alexandria Railroad, the series of rivers bisected by the tracks and if reached in time could shield them from the enemy. Just as influential, many of the aggressive generals Lee previously relied on for such movements had fallen in recent battles or been reassigned to the Army of Tennessee. His knockout punch proved to be a mere slap.

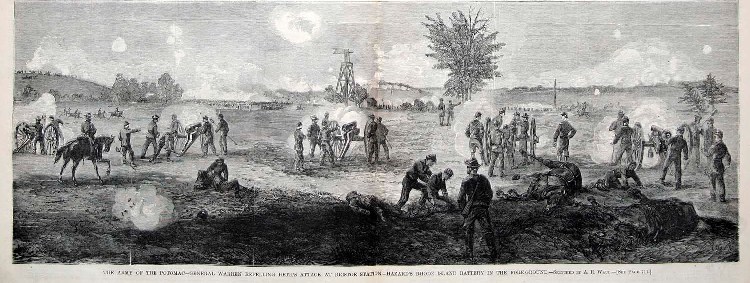

On the morning of October 14, with both armies still racing north, Gouverneur K. Warren’s II Corps had the head start on nearby Confederates and began crossing Broad Run to catch up with the III and V Corps in advance. Their haste convinced Ambrose P. Hill of their vulnerability and those isolated on the south of the river afforded a golden target. Hill ordered immediate assault, before the ground could be scouted and before supporting troops—following behind on a shared, crowded road—could be positioned.

When the first elements of attackers—North Carolinians from John R. Cooke’s and William W. Kirkland’s brigades—neared the Federal position, they discovered a well-entrenched foe awaiting their arrival. The Orange & Alexandria provided a perfect defensive line additionally serving as a screen to mask their numbers—just as the unfinished railroad had for Stonewall Jackson at Second Manassas. Warren’s men delivered devastating volleys into the Tarheels and captured artillery sent to oppose them before continuing unmolested across Broad Run.

Safely ensconced into strong fortifications around Centreville, Meade faced strong criticism for his retreat. “Lee is unquestionably bullying you,” chided Henry Halleck, chief of all Union armies. But the Confederate commander realized his soldiers did not share the offensive potential displayed during his previous northern invasions. “I do not deem it advisable to attack him in his entrenchments, or to force him further back by turning his present position…which we are not prepared to invest,” he wrote to Jefferson Davis. He painted a different picture to his wife: “I could have thrown him back, but saw no chance of bringing him to battle, and it would only have served to fatigue our troops by advancing farther. I should certainly have endeavored to throw them north of the Potomac; but thousands were barefooted, thousands with fragments of shoes, and all without overcoats, blankets, or warm clothing. I could not bear to expose them to certain suffering and an uncertain issue.”

To A.P. Hill, as the two rode across the battlefield the next morning surveying the carnage still on display, he simply said, “Well, well, General, bury these poor men, and let us say no more about it.” He would never again lead a serious offensive against Washington in the war.

Interesting that in late 1863, there would be two potentially great battles that didn’t take place. Lee chose not to attack the strong fortifications and defenses put together by Meade at Centreville, and of course Meade ‘returning the favor’ at Mine Run the next month.