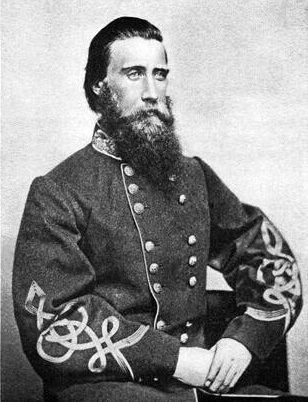

Top 15 Posts of 2013—Number 2: Review of John Bell Hood: The Rise, Fall, and Resurrection of a Confederate General by Stephen M. Hood

Newton’s second law of motion, roughly paraphrased, informs us that “an object at rest stays at rest, while an object in motion stays in motion, unless acted upon by an outside force.” This law of physics encapsulates Stephen M. Hood’s work of history John Bell Hood: The Rise, Fall, and Resurrection of a Confederate General, which reexamines the historical trajectory of the controversial Southern commander and seeks to push Hood historiography, often quite critical of the general, onto a new path. Indeed, Stephen Hood’s work is not so much a biography as a challenge to much of the existing scholarship on General Hood.

Boldly claiming that “some of the most well-known and influential historians of the 20th and 21st centuries,” regularly “misused sources, ignored contrary evidence, and/or suppressed facts sympathetic to Hood,” Stephen Hood seeks to highlight and rectify these mistakes, redeeming the Southern general in the process. While the results of his endeavor are mixed, there can be no doubt that Stephen Hood’s work is a force to be reckoned with, guaranteed to raise your eyebrow on more than one occasion.

John Bell Hood does not enjoy a popular place in Civil War literature. Viewed as a wild, reckless brigadier-turned-lieutenant general, Hood’s 1864 tenure of the Confederate Army of Tennessee in particular earns the scorn of most historians. Author Stephen Hood, who is indeed a distant relative of the general, offers a thorough re-examination of virtually every charge laid against Hood. Earlya chapter are devoted to Hood’s youth and his relationships with prominent Confederate leaders, including Robert E. Lee. The bulk of the book grapples with Hood’s tough tenure during the 1864 Atlanta and Franklin/Nashville campaigns. Final chapters reevaluate commonly-held misconceptions about the general, including his supposed addiction to opium and his fondness for frontal assaults.

Such a rework in needed, we are told, due to prior historians’ misuse (incorrect citations, misinterpreted sources, etc.) or lack of primary sources supporting their claims. Moreover, Hood charges that many scholars cite prior secondary works of other historians too liberally, thus propelling mistakes into succeeding generations of literature. Stephen Hood does not shy away from controversy here—John Bell Hood challenges the scholarship of well-known scholars such as Stanley Horn, Thomas Connelly, and especially Wiley Sword. Albert Castel, Craig Symonds, and John Lundberg and others also come under Hood’s fire at times. These are big names, men who are really the architects for our understanding of the Civil War in the Western Theater. Yet Hood’s work does indeed uncover surprising scholarly mistakes that raise some serious questions about historical scholarship.

As a small example of Stephen Hood’s criticisms, take the often-cited phrase that General Hood was “all lion, no fox.” Stephen Hood notes that this phrase originated from Stephen Vincent Benet’s poem “John Brown’s Body” from 1928. Yet historians have consistently and incorrectly attributed or implied this quote belonged to Robert E. Lee. Eddy Davison and Daniel Foxx’s biography of Nathan Bedford Forest charges that Lee thought Hood, “was ‘all lion and no fox.’ Lee was absolutely right.” Wiley Sword’s work implies that the quote came from Lee. Archer Jones and Herman Hattaway’s How the North Won the Civil War says “‘All lion, none of the fox,’ Robert E. Lee said of Hood.” James McPherson’s Battle Cry of Freedom puts the quote in Lee’s mouth as well, citing Jones and Hattaway. Thus a poet’s clever phrase from sixty-three years after the Civil War thus becomes a critique straight from the mouth of Robert E. Lee. These types of errors are startling, and Stephen Hood’s work points out wagon-loads of them.

Errors such as these raise rough questions for historians, amateur and academic alike. Are we too reliant on secondary sources when producing our own narratives? Are our interpretations of events supported by the primary evidence we have gathered? Granted, historians must rely on secondary sources to a degree, something Stephen Hood fails to acknowledge. Indeed, historians have a responsibility to understand the arguments that other historians have made. Secondary sources provide us with base narratives, which we can then support or challenge. Still, Hood’s book highlights how even the best historians can repeat mistakes made by others, and the worst historians might be drawing questionable conclusions from scanty and/or misinterpreted sources. Frankly, it is refreshing (if somewhat frightening) to see someone really investigating the footnotes. After all, the devil is in the details. At the very least Stephen Hood’s work is a call for more careful and in-depth scholarship.

The strongest chapters of Stephen Hood’s book are the reexaminations of John Bell Hood’s generalship during the Atlanta and Nashville campaigns. Stephen Hood convincingly argues that Hood, thrust into an untenable situation in the trenches around Atlanta, delayed the fall of the city by weeks and boldly brought the war to the enemy’s doorstep with his subsequent invasion of Tennessee. The Tennessee invasion’s strategy was sound and the battles of Franklin and Nashville came closer than most realize to shattering the Union’s hold on the region. Certainly Stephen Hood adeptly conveys the panic the invasion stirred among the Union high command. The invasion’s failure, Hood contends, lies largely at the feet of General John Bell Hood’s subordinates. These chapters offer a fresh and convincing reinterpretation of John Bell Hood’s generalship, and military historians should take note.

While Stephen Hood’s work does succeed in making us questions the conclusions of others, his scholarship himself is not above reproach. First, Stephen Hood’s book is forthright about its pro-Hood bias: “this book,” Hood writes, “does not require balance because it represents the balance that is missing from most modern books…published about [General] Hood.” Perhaps this is true, but two wrongs don’t necessarily make a right. Finishing this book, it’s hard to shake the feeling that Hood comes off squeaky clean, personally and professionally. Surely some blame must rest at Hood feat for his invasion’s failure? Stephen Hood defends the Southern general at every turn, and in doing so, makes the reader wonder what he isn’t discussing.

Second, considering the weighty names that Stephen Hood challenges in his work, it is imperative that he establish the soundness of his own historical judgment with the reader. This he doesn’t quite do. In an early chapter, Stephen Hood contends that historians have inaccurately depicted Robert E. Lee’s opinion of John Bell Hood. In a series of two telegrams, Jefferson Davis inquired of Lee his thoughts on Hood as commander of the western army. Stephen Hood provides the texts of those messages to allow the reader to judge for themselves. I’ve placed them at the bottom of the article for you to read as well.* Stephen Hood argues that Lee is in favor of Hood, “making five positive comments and one negative.” Yet many historians, including myself, interpret Lee’s message as being rather critical of Hood, certainly not a ringing endorsement. Read the telegrams yourself; see if you can’t see the plausibility of both interpretations. Thus, what Stephen Hood castigates as “patently untrue” arguments by historians may simply be interpretations he himself doesn’t agree with or see. There are times throughout the book whether one wonders if the authors Hood is condemning truly blundered, or simply came to differing conclusions. John Bell Hood raises questions about other scholars’ work, yes, but it also raises a few questions about Stephen Hood’s scholarship as well.

Lastly, it is worth mentioning that Stephen Hood seems to trust completely John Bell Hood’s post-war memoirs Advance and Retreat. Although Stephen Hood reminds of the importance of primary sources, those sources can still be quite deceptive. Considering that General Hood’s memoirs were written in the midst of a post-war, Lost Cause, mud-slinging feud, certainly we should take Advance and Retreat with a grain of salt. Nowhere in Stephen Hood’s book does he deeply discuss General Hood’s memoirs, their veracity, or why he chose to put so much belief in them.

Ultimately, this is a book that belongs on Civil War bookshelves, especially for those interested in either General Hood or the war in the west. Stephen Hood has written a powerful critique on Hood scholarship, raising important questions both about how historians write and how historians have treated Hood. At times convincing, at other time less so, it is ultimately a book that, while not definitive or conclusive, certainly pushes our understanding of John Bell Hood and his war to the next level. It is a book to be reckoned with, and I surely hope that others (historians and readers both) will offer their thoughts, opinions, support and criticisms of it.

John Bell Hood: The Rise, Fall, and Resurrection of a Confederate General by Stephen M. Hood. Savas Beatie LLC, 2013. ISBN: 978-1-61121-140-5. 335 pp., $32.95.

Appendix

*Lee’s first telegram to Jefferson Davis on July 12, 1864: Telegram of today received. I regret the fact stated. It is a bad time to release the commander of an army situated as that of Tennessee. We may lose Atlanta and the army too. Hood is a bold fighter. I am doubtful as to other qualities necessary.

Lee’s second telegram to Jefferson Davis later that evening: I am distressed at the intelligence conveyed in your telegram today. It is a grievous thing to change commander of an army situated as is that of the Tennessee. Sill if necessary it ought to be done. I know nothing of the necessity. I had hoped that Johnston was strong enough to deliver battle. We must risk much to save Alabama, Mobile and communication with the Trans Mississippi. It would be better to concentrate all cavalry in Mississippi and Tennessee on Sherman’s communications. If Johnston abandons Atlanta I suppose he will fall back on Augusta. This loses us Mississippi and communications with Trans Mississippi. We had better therefore hazard that communication to retain the country. Hood is a good fighter, very industrious on the battle field, care less off, and I have had no opportunity of judging his action, when the whole responsibility rested upon him. I have a high opinion of his gallantry, earnestness and zeal. General Hardee has more experience managing an army. May God give you wisdom to decide in this momentous matter.

Zac Cowsert received his Bachelor of Arts Degree in History and Political Science from Centenary College of Louisiana, a small liberal-arts college in Shreveport. He is currently a graduate student at West Virginia University focusing in U.S. History and the American Civil War. His studies and research often explore the Trans-Mississippi Theater. ©

I have read this book and i find it opens up many questions which may be looked at in the future.the author has a second book coming out i believe in june 2014 which will have all the newly discovered papers of JBH in it.Hopefuly this will enlighten us to his research.i have not heard of any comments from Wiley Sword who the author seemsto attack the most.if available i would love to see them.

I knew this was gonna make the Hit List! Caused quite a kerfluffle, it did! Loved that!

Zac,

Thanks for the honor.

A response to one of your comments if I may.

You state that I seem “to trust completely Hood’s post-war memoirs “Advance and Retreat.” That’s a fair criticism. However, the reason I indeed consider Hood’s memoirs as a credible primary source is because after I came upon Hood’s personal papers in the summer of 2012 I spent a considerable amount of time reconciling the contents with what he wrote in A&R, and found ZERO instances where Hood wrote anything that was inconsistent with any piece of paper in his collection. Not every assertion by Hood in A&R had backup paperwork, but the contents of every letter and document within his papers that appears in A&R is correct. It appears that if Hood wrote anything inaccurate or incorrect in A&R, it was because he had received erroneous information from others to whom he had written asking for info.

The only conflict that I found is where Hood wrote that he could only “recall” writing two letters to Richmond after joining Joe Johnston’s army in the spring of 1864; a letter to Bragg and one to Davis. We know in 2013 that there were some others, but it is important to note that of the other letters Hood is now known to have written, NONE are in his work papers. So there is no proof that Hood lied when he said he could only remember writing two letters to Richmond. (And by the way, those two letters appear to be Hood simply answering questions in letters he had received from Bragg and Davis.)

In my forthcoming book “The Lost Papers of Confederate General John Bell Hood” (Savas Beatie, Spring 2014) I have an entire chapter on the credibility of “Advance and Retreat” as related to the contents of Hood’s newfound personal papers.

Regards,

Stephen M “Sam” Hood