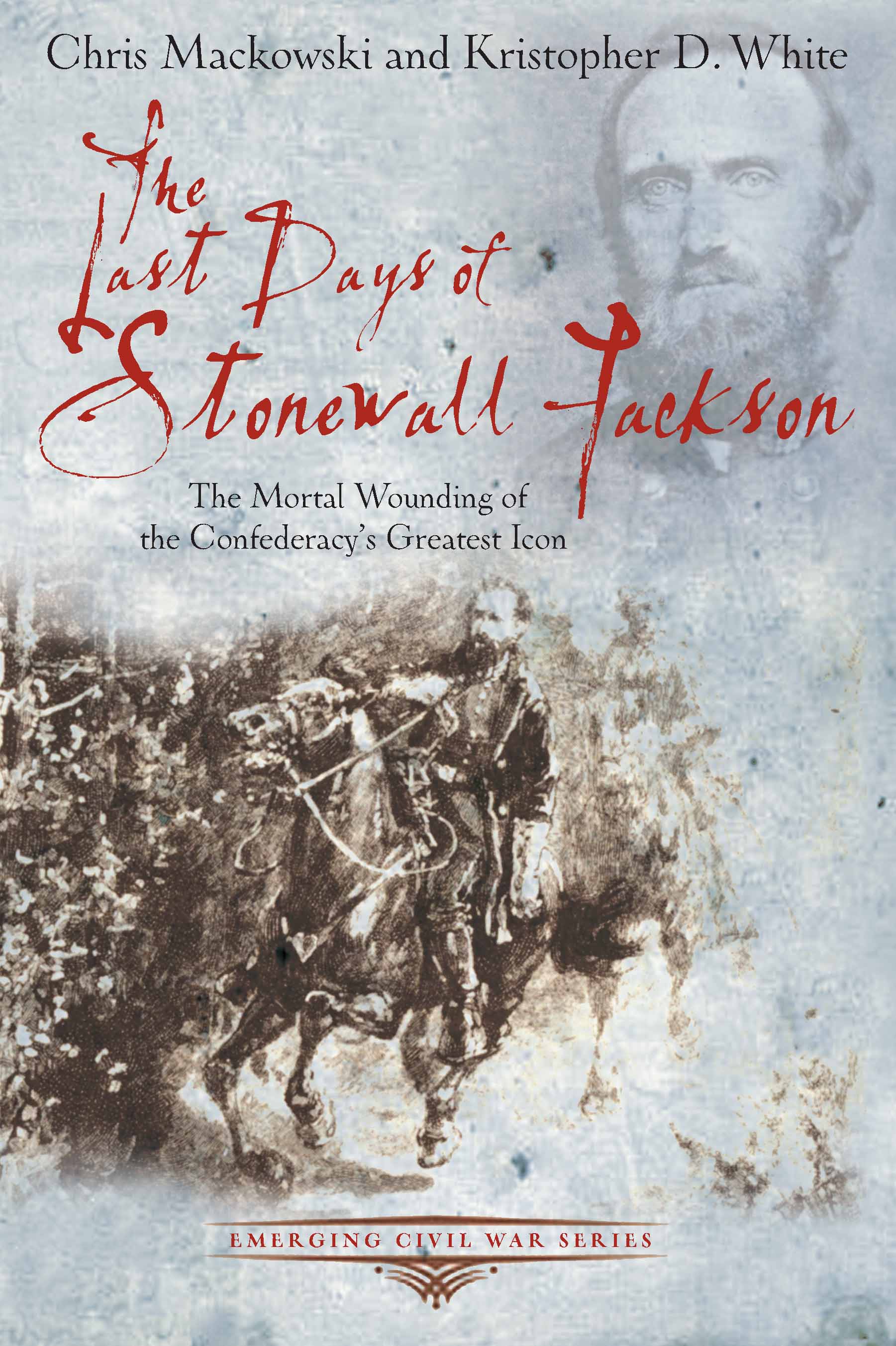

The Death of a Confederate Icon: an Excerpt from “The Last Days of Stonewall Jackson” Authored by Chris Mackowski and Kristopher D. White

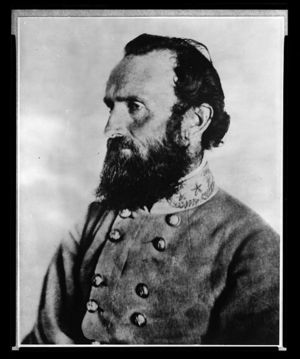

Today marks the 151st anniversary of the death of Confederate General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson. Jackson had been wounded by members of the 18th North Carolina Infantry on the evening of May 2, 1863. The wounding necessitated the amputation of his left arm, in the early morning hours of May 3rd. Om May 4th, Jackson was transported to Guinea Station, Virginia. Guinea Station was located 27 miles south east of the Chancellorsville Battlefield. There Jackson was to be placed on a train and taken to recuperate in Richmond. As his staff arrived in advance of the general they found the tracks to the south torn up by Union cavalry.

Today marks the 151st anniversary of the death of Confederate General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson. Jackson had been wounded by members of the 18th North Carolina Infantry on the evening of May 2, 1863. The wounding necessitated the amputation of his left arm, in the early morning hours of May 3rd. Om May 4th, Jackson was transported to Guinea Station, Virginia. Guinea Station was located 27 miles south east of the Chancellorsville Battlefield. There Jackson was to be placed on a train and taken to recuperate in Richmond. As his staff arrived in advance of the general they found the tracks to the south torn up by Union cavalry.

For the next few days, Jackson was housed at “Fairfield”, the 744 acre plantation of Thomas Coleman Chandler. At first Jackson seemed to be doing fine, but on the morning of May 7th he awakened with pain in his side, a high fever, and nausea. Jackson’s primary care physician Hunter Holmes McGuire diagnosed him with pneumonia. The same day of Jackson diagnosis the train tracks were restored. Three doctors arrived from Richmond, supposed pneumonia specialists. Along with the doctors came Virginia Governor John Letcher, Jackson’s wife Mary Anna, and his young daughter Julia. Five doctors eventually tended to the patient, who was too ill by this time to move to Richmond.

By May 10th it was evident Stonewall would not make it through the day. The following is a chapter excerpt from “The Last Days of Stonewall Jackson,” authored by Chris Mackowski and Kristopher D. White.

….Mary Anna seldom left her husband’s bedside except to go to Julia. At one point, near the end, she brought the baby in, which elicited a delighted smile from her husband. “Little darling! Sweet one!” he said, calling the child his “little comforter.” He watched her intently, “with radiant smiles,” then he closed his eyes and raised his hand over her, committing her to God. “Though she was suffering the pangs of extreme hunger, from long absence from her mother, she seemed to forget her discomfort in the joy of seeing that loving face beam on her once more,” Mary Anna later recalled. “She looked at him and smiled as long as he continued to notice her.”

Mary Anna, Rev. [Beverly Tucker] Lacy, and other members of Jackson’s staff all prayed with Jackson during those few days. They read Bible verses and sang hymns, including one based on Psalm 51, which Jackson had treasured as one of his favorites:

Show pity, Lord; O Lord, Forgive;

Let a repenting rebel live;

Are not thy mercies large and free?

May not a sinner trust in thee?

Meanwhile, McGuire and his team of doctors tried everything they could to counteract the pneumonia—but to no avail. “I see from the number of physicians that you think my condition dangerous,” Jackson told McGuire on Saturday, May 9, “but I thank God, if it is His will, that I am ready to go. I am not afraid to die.”

By that evening, Jackson’s fever and restlessness had increased, and “although everything was done for his relief and benefit, he was growing perceptibly weaker,” Mary Anna noticed.

McGuire quietly admitted that recovery looked hopeless.

On the morning of Sunday, May 10, Dr. Morrison, kinsman and family physician, broke the news to Mary Anna. “[T]he doctors, having done everything that human skill could devise to stay the hand of death, had lost all hope,” Mary Anna later recalled. “[L]ife was fast ebbing away, and they felt that they must prepare me for the inevitable event, which was now a question of only a few short hours.”

Mary Anna needed a few moments to collect herself from the “stunning blow.” She realized, she told Dr. Morrison, that she had to break the news to her husband. He would want to know. He would want the time to prepare himself. “This was all the harder,” Mary Anna wrote, “because he had never, from the time that he first rallied from his wounds, thought he would die, and had expressed the belief that God still had work for him to do, and would raise him up to do it.”

Mary Anna reentered Jackson’s room and took her position at his bedside, praying for the strength to hold her composure. Jackson appeared to be sinking fast into unconsciousness, but Mary Anna’s voice, when it finally came, seemed to rouse him. “Do you know the doctors say you must very soon be in Heaven?” she asked.

At first, Jackson did not seem to understand, so Mary Anna repeated her question. After making much effort to shake off his stupor, Jackson finally replied: “I prefer it.”

“Well,” she told him, “before this day closes, you will be with the blessed Saviour in His glory.”

Mary Anna finally broke down. She fell across the bed and bitterly wept. After she calmed, Jackson called for McGuire. “Doctor, Anna informs me that you have told her I am to die today,” he said. “Is it so? McGuire confirmed it was, indeed. Jackson looked to the ceiling for a moment, as if in intense thought. “Very good,” he finally said. “Very good. It is all right.”

The clock on the fireplace mantel ticked by the day’s slow minutes. Jackson told Mary Anna he had so much he wanted to say to her but was too weak. They did manage to discuss some of his last wishes, where he wanted to be buried, where he wanted her to go after his death.

Members of Jackson’s staff came in for final interviews. Many of them wept openly. Sandie Pendleton cried so hard he had to excuse himself and walk outside. Jim Lewis sobbed inconsolably. “Tears were shed over that dying bed by strong men who were unused to weep, and it was touching to see the genuine grief of his servant, Jim, who nursed him faithfully to the end,” Mary Anna wrote.

Jackson maintained a peaceful demeanor throughout, due in large part to the drugs but also due to the strength of his faith. “It is the Lord’s day,” he said at one point. “My wish is fulfilled. I have always desired to die on a Sunday.”

McGuire offered Jackson some brandy and water, but Jackson demurred. “It will only delay my departure, and do no good,” the general said. “I want to preserve my mind, if possible, to the last.”

At army headquarters, where the Reverend Lacy conducted a prayer service, some 1,800 soldiers attended. Afterwards, General Lee took the chaplain aside. “When you return, I trust you will find him better,” Lee said. “When a suitable occasion offers, tell him that I prayed for him last night as I never prayed, I believe, for myself.”

But Lacy would not return to Fairfield in time.

By three o’clock, Jackson had slipped entirely into delirium. Distraught by his patient’s condition, McGuire would excuse himself from the room—“unable in my enfeebled condition to restrain my grief at seeing him die,” he later admitted in a private letter to a friend.

From his deathbed, Jackson called out more battle orders. “Push up the columns,” he ordered. “Hasten the columns! Pendleton, you take charge of that! Where’s Pendleton? Tell him to push up the columns! Order A.P. Hill to prepare for action! Pass the infantry to the front rapidly! Tell Major Hawks—”

He stopped in mid-sentence, and his countenance relaxed. Witnesses noted that a “smile of ineffable sweetness spread itself across [Jackson’s] pale face” and his voice softened “as if in relief.”

Quietly, Jackson said, “Let us cross over the river, and rest under the shade of the trees.”

And then the thirty-nine-year-old Jackson died.

In that moment, even the ticking clock on the mantel would hold its clockwork breath. McGuire would stop its swinging pendulum, would freeze that instant of time, to mark the time of death.

“Without pain,” said McGuire, “or the least struggle, his spirit passed from the earth to the God who gave it.”

Thanks Chris! Do you or anyone know where I can get more info on Julia the daughter? Have there been any books on her and Mary Anna?