Honoring Petersburg’s Fallen: Memorial Day 2014 at Pamplin Historical Park

This afternoon it was my honor to participate in a Memorial Day commemorative program at Pamplin Historical Park reflecting on the lives lost on Petersburg’s western front during the last days of the campaign. The day’s events included costumed interpretation of civilian and military life in the 1860s, guided tours, and an artillery demonstration followed by the playing of taps. The following is a transcription of my talk:

This afternoon it was my honor to participate in a Memorial Day commemorative program at Pamplin Historical Park reflecting on the lives lost on Petersburg’s western front during the last days of the campaign. The day’s events included costumed interpretation of civilian and military life in the 1860s, guided tours, and an artillery demonstration followed by the playing of taps. The following is a transcription of my talk:

Whether a 4th grade elementary student first experiencing a battlefield and grasping what the word “war” really means, a self-professed Civil War buff adding this place to a bucket list of major battlefields, an army officer on a staff ride learning the still relevant lessons of leaderships and logistics from the Petersburg Campaign, or simply a citizen searching for another piece of their nation’s identity, most visitors to Pamplin Historical Park will hear the story of Captain Charles Gilbert Gould, a young officer from Windham, Vermont who arguably was the very first Union soldier over the Confederate earthworks during the April 2, 1865 battle. Gould’s fight for his life took place within a rifle’s accurate shot from the Battlefield Center at the park.

The rifle aimed directly at nineteen year old Captain Gould as he mounted the parapet that April morning failed to fire, though a saber blow to the scalp and bayonets thrust all the way through his jaw and another nearly to his spine left the captain in precarious condition. Charlie survived his wounds and lived until the age of 71 working in the Pension Office, War Department, and Patent Office. In 1890 he was awarded the Medal of Honor for his heroic actions during the Breakthrough. We feature Charlie’s story here at Pamplin Historical Park not only for the tremendous implications that his actions and those of the waves of comrades behind him would have on the course of the war, but to put oneself in Charlie’s nervous shoes lying on the cold, wet ground for three and a half hours awaiting the signal gun’s prompting. Charlie could scarce imagine the reverberating impact of the thousand yard charge he was about to undertake. A charge that would act as a catalyst of the events leading up to the final surrender at Appomattox in one weeks’ time, and a charge that would resonate in hundreds of homes around America whose loved ones would not be returning to their vacant chairs.

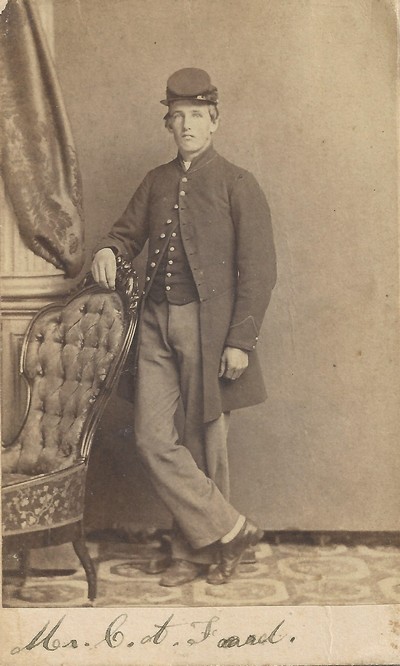

This Memorial Day, in addition to the triumphant story of success that Charles Gould experienced, we want to remember soldiers like Charles Ford of the same company who was just seconds behind his captain in scaling the earthworks. The musket pointed at Charlie Ford did fire joining the twenty-two year old with his older brother John who fell at Mine Run in November 1863 and younger brother Hadley who fell at Spotsylvania in May 1864 in early graves. “It seems a hard fate to perish in the last struggle, after having passed safely through so many,” wrote a recuperating Vermont soldier after learning the fate of many of his friends at the Breakthrough. It is easy to let a program of as morbid a nature as battlefield deaths depress one, indeed there were times when researching this program that I had to step away after reading successive sad stories. But these tragic tales continue to inspire, just as the fallen inspired their comrades on that April morning.

“A sad death, you say, for one so young?” spoke Ella French on Memorial Day, 1885, in remembrance of her brother, Lieutenant George Oscar French of the 1st Vermont Heavy Artillery who fell early in the assault. “A sad death, yes and no.” She told of her experience meeting a comrade of George’s the previous summer. Lieutenant French’s actions during the Breakthrough still resonated with this total stranger who told Ella and her sisters all about his final moments. In previous charges this particular company had faltered during the critical moment and the survivor attested it to poor leadership. That fateful morning, however, Lieutenant French appealed in every form he could think in the hurry of the moment before the charge, reminding them that they would want the people of Vermont to be proud. Honor bought with blood for a state could only go so far, indeed George French quite feared an assault on the Confederate position, writing his father the previous day about the “dreadful slaughter” that an attack would certainly bring. But his final words, his final actions, clinched the deal for his troops. “I will ask you to go nowhere that I do not go first and if I die, go on over my dead body, but go one.” The stranger attested this was the first time they had ever been officered by a man.

Ella remembered that this plain working man like her brother, “had carried through these twenty years the memory of those fearless words sealed by that early death, and so felt kinship in that work and courage that he spoke of them with kindling eye and choking voice… And doing so, surely our brother’s death has borne tenfold more fruit than would a long life, ignobly or indifferently lived.”

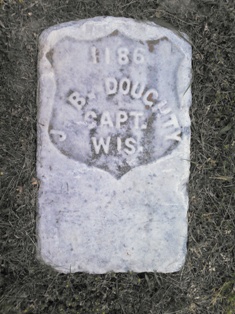

The entire Union Sixth Corps massed for assault in front of Forts Fisher and Welsh, one mile’s distance to your left. Its regiments hailed from New York City, from Philadelphia, from the divided border state of Maryland, from the green mountains of Vermont. They fought for the land of their ancestors. They fought for their land of new opportunity. John B. Doughty, born in England, sought a better future in America and moved to Wisconsin. He boarded with a family in Racine before serving a as captain in the Fifth Regiment of Infantry. Sitting on a log with two of his messmates the night before the Breakthrough, he commented that “at least one-third will fall, and of the three I feel a strange presentiment that I shan’t come out of it.” The captain was shot in the head while urging his men forward through the first line of abatis. A fellow Brit, one of the two who shared mess with Captain Doughty through the war and was alongside him for the cedar log council eulogized that “England offered no brighter, holier tribute at Liberty’s shrine than the life of John B. Doughty.”

Augustus Hemple, a German immigrant serving in the 87th Pennsylvania, shared Doughty’s concern the night before the battle, expressing: “If we have to charge those works, I will never get over alive.” Hemple begged for someone to watch over all of his worldly possessions—ten dollars and a watch—and return them to his mother after the war, should he fall. George Blotcher refused, saying that Rebel bullets would be flying his way as well. Blotcher survived the assault, Hemple did not. George searched his friend’s body for the precious cargo to return to Mrs. Hemple who had lost another son in the war.

William Phillips of the 5th Wisconsin reassured his parents even after being amputation of his arm following the Breakthrough. “His spirits are good and he is cheerful trusting in the Lord,” wrote the regimental chaplain to William’s father the day after the battle. “He wishes me to say that you need not come on to see him as he thinks he shall do nicely.” “My arm is doing as well as can be expected,” William attempted to calm his parents’ nerves in a letter home eleven days after the battle, but he was feeble on account of being continuously moved from battlefield to field hospital to division hospital to City Point to Lincoln Hospital in Washington, DC. The next letter to Stevens Point, Wisconsin began, “It was like a brother when they took William from us.” He had died the same day he had written to relieve his parent’s worries.

Albert Bucklin hurried from Danby, Vermont to Washington, DC immediately upon hearing of his son George’s wounding during the Breakthrough. George was a man of few words and friends, but was remembered for being “ever faithful, patriotic, and brave.” He stood high in the estimation of the comrades who hardly knew him as a person but could depend on him as a soldier. Albert Bucklin arrived too late to see his son once more and only had a lifeless body to return to Vermont. That was still more than some families had.

After the war, William Scattergood Ackley’s mother went to Petersburg and enlisted the help of a guide to scour the battlefield for her bright-eyed boy’s grave. Her heartbreaking search was to no avail, Ackley likely joins 4,579 unknown soldiers buried in Poplar Grove National Cemetery. He had served in the 4th New Jersey Infantry with much distinction. He carried the regimental colors as sergeant during the Battle of the Wilderness. Thirty-seven bullets and three pieces of shell pierced the flag he carried. Ackley himself was badly wounded in the legs and required special treatment in a Pennsylvania hospital. By 1865 he could walk again but only with the aid of crutches. A request to rejoin his regiment was denied, the surgeon instead returning him to his parents to continue his recovery. Ackley went AWOL from home, reuniting with his unit just before the beginning of the spring campaign. Despite his limp he was among the first of his unit to climb the breastworks, laying his hands on a Confederate cannon, shouting, “Come on, boys, come one,” dying with the words still on his lips. A comrade described him as “the bravest and best-liked men in the regiment.”

James William Bromley on the other hand was not always the best soldier in the 2nd Vermont Infantry. During the winter of 1863, the captain of his company was walking down a road near the camp when he heard a rustling in the bushes nearby and looked in discovering Private Bromley preparing to dress a yearling sheep whose throat he had just cut. Orders against unauthorized foraging were strict in the company, and the captain went after James sharply for his violation. James looked up started with a half comical, half frightened expression, and with pleading innocence, claiming, “Yes captain, orders are all right, but I ain’t going to allow any darned sheep to bite me.” He was a peculiar fellow in many respects according to another Vermonter, but underneath his apparent oddity his heart beat true to the cause of the Union. After his re-enlistment that winter, he assumed a serious determination to see the rebellion put to an end. For meritorious conduct he became sergeant and earned a furlough in 1865 to visit his home in Danby. Movements at the front indicated the culmination of the long campaign around Petersburg and Richmond and James grew uneasy at home. “I guess they can use Jim Bromley to about as good advantage down yonder now as ever,” he told his family and started back to the front before the expiration of his leave of absence. Bromley met a soldier’s death in the hour of final victory.

Corporal Henry Green Fillebrown also did not have to participate in the Breakthrough. At the time he was currently on furlough, a temporary reward earned by having presented the most soldierly appearance of all non-commissioned officers in his regiment. During the war he sent half of his pay home to his elderly father James who was now too feeble to support himself. James had taught himself brick-making and traveled in between farming seasons to employ his trade to earn a living for his large family. Now it was Henry who traveled, going without a scratch for nearly four years during the war. He had an excuse from service on April 2, 1865, but had been with his regiment in its every engagement of the war and would not permit it to go into battle without him. His peers regarded him as the best soldier in the company… he was its only casualty during the Breakthrough. His father James struggled to live off of Henry’s backpay until the paperwork for the pension was finally accepted.

This selfless sacrifice was not a universal distinction among all soldiers. A New York lieutenant asked for a leave of absence just days before the commencement of the campaign, fearful of what lay ahead. His commander had to deny that request, a decision he regretted when he saw a shell directly strike the rifle pit the lieutenant and two others temporarily sought cover in. But why did Captain Ackley, Sergeant Bromley, and Corporal Fillebrown neglect their own personal safety? Why did they return early to their units, when their loved ones clearly needed them at home. “I do not expect to live through the war,” confided John C. Goldthwait, an infantry captain from Maine, but instead of shirking his duty, hiding in the rear, or taking cover once the going got tough, the captain expressed that he “must win glory and honor before I go. As well here as elsewhere.” During the fighting on March 25th that preluded the Breakthrough his request was filled. The brigade’s position was vulnerable to flank attack and the commanding brigadier had to sacrifice the Maine regiment to plug the hole. Goldthwait was the first man to fall, dying instantly. Perhaps the words of another Vermonter will also yield some understanding into the motivations and beliefs of these fallen.

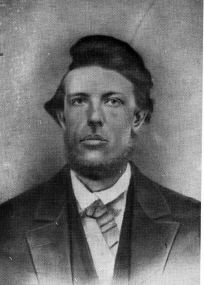

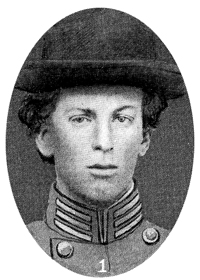

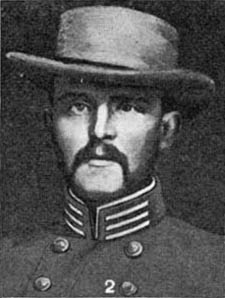

Charles Carroll Morey enlisted as corporal into the Second Infantry Regiment on April 22, 1861. During his service, he suffered wounds in the Bloody Angle at Spotsylvania Court House and during Sheridan’s Shenandoah Valley Campaign. While convalescing, he wrote, “I think it is wrong for one who is able to do duty to stay away.” Upon his healing, he happily exclaimed, “Once more I find myself with the Regiment, and feel as though I had gotten home.” Morey would have been happy in Royalton, Vermont if there was no war, “but as it is the war must be settled then I will come home and try to be content with a quiet citizen’s life.” With promotion to captain, Morey continued in his conviction: “I think I would enjoy being home very much if the war was ended and an honorable peace once more established but this little job must be accomplished first.” Anxious as he was for the job to be complete, he expressed concern about his return home, previously confiding to his sister that: “Society will not own the rude soldier when he comes back, but turn a cold shoulder to him, because he has become hardened by scenes of bloodshed and carnage. But I tell you, dear sister, there are feelings, tender feelings, deep down in the soldier’s breast, which when moved will prove that all that is good is not quite dead.”

Morey struggled with his identity crisis between soldier and civilian, with belonging at home with his family or belonging in the field with his unit. He expressed confidence and doubt in the same sentence in a letter to his mother written March 31, 1865: “We hope and pray that we may be able to strike the death blow to the rebellion before many days but perhaps we may fail, yet we hope for the best and will work hard for it and trust in God for the accomplishment of the remainder. Now is the time that we need divine assistance, pray for us that we may accomplish all.”

Captain Charles Carroll Morey survived the initial Breakthrough the morning of April 2, 1865, but was mortally wounded during an assault on Lee’s headquarters at Edge Hill on the outskirts of Petersburg. “It is with great pain to me that I take my pen to inform you of the death of your son,” wrote a fellow captain in the 2nd Vermont. “I was by his side when he fell. He was killed by a grape shot striking him in the right shoulder and breaking it badly. He lived about twenty minutes after he was hit. I stayed with him until he breathed his last. He never spoke after he was hit, but he recognized me for about a minute. I closed his eyes and saw him carried off the field by some of the men of his own company and the buried him with as much respect as possible. There was a chaplain with the men when he was buried and he made a prayer at his grave… his name written on a board and nailed on a tree by his head.” After the war, Morey’s body was re-interred at Poplar Grove National Cemetery and is one of the first greeting visitors to the final resting place of the 6,718 total number Civil War casualties buried there.

Is there even a proper way to die for the over 250,000 combat fatalities of the American Civil War? William Fields thought so. He met Sergeant Major Marion Hill Fitzpatrick of the 45th Georgia Infantry while sharing a makeshift hospital in a private residence in Manchester, just on the other side of the James River from Richmond. Fitzpatrick’s right thigh was shattered to pieces during the Breakthrough, the wound being too high up on the leg for amputation. His life expired four days later. “My prayers are that God will sustain you in your troubles and loss,” Fields attempted to console Marion’s wife Amanda, a total stranger to him. “Your husband and myself have shared the same dangers under the same army for the past four years although I did not get acquainted with him until he was wounded… He died as I wished to die.” While on furlough several months before his death, Marion and Amanda conceived a daughter. The Georgian likely never knew of his namesake daughter, Marion, born November 7, 1865. The little girl never meeting her father.

Some charged with the difficult task of bearing hard news struggled to find the words. “Mrs. Howard, how or what shall I say,” wrote a Vermont soldier to a recent widow of the Breakthrough. “It is only a soldier’s duty but to me this is a painful one. Sergeant George J. Howard is dead. His fighting for his country has ended. We have lost a noble soldier, but what is that to your loss.”

Death did not discriminate between noble or cowardly, rich or poor, eloquent or ignorant, confident or petrified, stoic or jokester, Union or Confederate.

Private Joshua W. Bowman of the 37th North Carolina Infantry lost one brother at Gettysburg, one at Spotsylvania, and another to disease. He and his wife Eliza had four children, the last one conceived in late 1863 while Joshua recuperated at home from his own wound suffered at Gettysburg. He was wounded again July 30, 1864 in action related to the explosion at the Crater. By September of that year he was back with his regiment. Boon Little remembered Private Bowman beside him in the breastworks at Petersburg on April 2, 1865, performing his duty until he was shot down instantly as blue-coated soldiers swarmed over the walls in the faint morning light. “He did not move or even groan,” Little recalled. His testimony had been enlisted by the widowed Eliza after the war, in desperate need for a pension to support her four children. Union cavalry had raided the family farm on April 14, 1865, confiscating the widow’s horse and leaving a worn out one in its stead which predictably died the next day. Unable to support her family on her own, she was about to give them up for adoption until a sister moved in to help keep the family intact.

Most of the killing during the Breakthrough came in the open fields in front of the Confederate earthworks and a brief hand-to-hand struggle upon the parapet. Union deaths exponentially dwarf their counterpart’s numbers, but the impoverished Bowmans were joined in grieving by the families of two well-educated members of the University of North Carolina Class of 1860.

John Daniel Fain was an only child who labored on his family farm until attending school at Chapel Hill. He enlisted as a private at the start of the war and rose meteorically through the ranks, suffering wounds during the Seven Days’ Battles and the Wilderness. Now, as an aside, a friend of mine recently underwent surgery that allowed him some time off from work. He definitely rubbed it in, gloating about milking every last day off possible before returning to the job. I can only imagine how much workman’s comp he would have gotten out of something like “gunshot wound to the left thigh.” But a fellow soldier in the 33rd North Carolina Infantry remembered Fain to be “the soul of honor—so manly, so heroic that no could help but loving him.” Despite the seriousness of his wound, he returned after a short absence to his company with a well-deserved promotion to captain. While observing the aftermath of the Breakthrough, a bystander heard the unmistakable thud now all too familiar to him as a stray bullet claimed the captain’s life. His grieving mother proudly clung to the dictionary John carried to class at UNC.

Captain Fain perhaps was familiar with another Tarheel in the Class of 1860 who served in Lane’s Brigade. Captain William T. Nicholson was also wounded in the 1864 Overland Campaign but returned in time to defend the Boydton Plank Road at Petersburg. William’s brother Edward was killed March 25 in the attack on Fort Stedman and William fell one week later. The regimental historian of the 37th North Carolina who fought on dozen of battlefields together with the captain found it a privilege “while receiving instructions from him, to watch him closely, and in all of these conflicts, no matter how trying the circumstances, I never saw him lose his balance. He was ‘born to command men,’ and had he lived he would have proved a great factor” after the war.

It is because of the tremendous sacrifice of these citizen soldiers that we gather here to remember them each year. A large portion of that generation’s of future parents, politicians, physicists, poets, lovers, and inventors taken away. Their potential in many fields went unrealized. But their actions on this field perhaps did more for this nation than a comfortable life spent at home. A Maryland preacher mourned the loss of Captain Thomas Ocker, but placed his lost life into the greater context: “While we regret that he has been denied the enjoyment of that peace which his efforts aided to bring to our country, we feel a proud consciousness that his life has been sacrificed in a noble and just cause, and that his memory will ever be cherished in association with the great and good who have also fallen.”

These soldiers knew the stakes in front of them before this battle began. They spoke with eloquence on their willing participation in this conflict. “Now the calamity is upon us,” claimed James Marsh Read at the start of the war:

A calamity which it is too evident might have been avoided, at least in its worst features, had the people done their duty in past years, in making the government of which they had control of what it should have been. It is a calamity which calls out all our power to meet, which comes home to e very family, and engrosses every mind with the sickening alternatives of hope and fear. Hope—for we can only hope that good will come from all our afflictions. Fear on every side, of deeper and further perils. It was said, ‘Happy is the people that have no history.’ Yet may we not say ‘Happier is the people whose history is the record of noble deeds, brave actions, patient endurance, high principles carried into action,—who learn from the errors of the past a better course for the future, and in the midst of calamities fail not, but work bravely on in the cause of freedom and justice?’ Is not this the record which every patriot would proudly claim as the highest glory he could wish for his native land?

Adjutant Read wrote to his parents April 3, 1865, “We had a glorious day yesterday… [but] you will be sorry enough to hear that I was severely wounded. I have lost my right foot. It was shot through lengthways and amputated just above the ankle joint. I am doing remarkably well, however and hope to get home soon. Yesterday’s work fully pays us all for what we have lost. I can give my foot for such a cause with goodwill.” Four days later, the Vermonter breathed his last, giving his all for that cause. “He is now cut down in his early prime, and just as a triumphant people is preparing to enjoy the fruits of a dearly bough and long wished peace,” remembered a friend. “He is gone, offered as a sacrifice on the altar of his country, yet he lives—his memory is freshly embalmed, is warmly cherished and will long continue to flourish—in the hearts of many surviving friends.” 149 years later Read’s memory, the memory of all who shared his battlefield, the soldiers who fought for generations before him, the soldiers who came after, those who will continue to fight in future calamities.

Had these soldiers survived for one more week of the war, they could have happily returned to their families, but the war required one last full measure of devotion from several hundred of them. The surrender at Appomattox required one final surge towards the once insurmountable trenches of Petersburg. “The turn of things on that memorable morning was a turn that filled the soul with gladness,” recalled a Ohioan who survived the charge. “At dawning of day, we could see comrades bleeding, dying and dead, and it was sad to see our fallen heroes, but high above the sobs of death could be heard the shouts of victory… At this stage of the battle, the light of day begin to dawn, not only the light of the rising sun in the east, but the light of the rising sun of justice, freedom and liberty, that shall forever shine on every American citizen. Yes, we trust it was the dawning of a new day that shall know no more rebels in our land, no North, no East, no South and no West, and shall know but one flag and that flag the stars and stripes.”

“What a glorious death to die on the enemy’s works with the wild shout of victory in your ears,” wrote a Vermont soldier who admitted to crying himself to sleep at the loss of many of brothers in arms. “Just at morn when all was still until we broke the stillness with yells, shouts, and soon with death groans. I shall never forget it or the noble soldiers who fell there.”

May their memory continue to live on in this great nation.

Another great piece, man.

Thank you for this very moving essay.

I have visited Pamplin Historical Park several times and think it is a great CW museum, possibly the best. It was never crowded on my visits which leads me to worry about its future. I encourage everyone to make a visit.

Edward,

Thank you for mentioning Captain Fain. I would like to tell you what happened to the 1859 Webster’s Dictionary that Captain Fain’s mother had. I was looking on Ebay back in 2012 and a person had it listed for 100.00. The will his mother left is posted online and she left the dictionary to a fellow classmate and veteran who I suppose kept in the family until it turned up in an estate sale and then to ebay. I purchased the dictionary and in May 2013 found a home for it with the Museum of the Confederacy in Richmond, VA. The dictionary was still in tact with his name signed in the front and the original red ribbon book mark. Probably my only chance of finding and rescuing such an incredible piece of history and it was well worth it! I still have pictures from when I had it if you would like those.

Thank you for your comment! I had seen an archived website for the sale of the dictionary but had no idea where it ended up. Living in Richmond myself, I will definitely make the time to check it out. I certainly appreciate this help!

I found the grave marker of John H.D. Fain in the woods at Kerr Lake in Vance County NC after a small fire burned the overgrowth that hid it. The maker mentions his death in battle. His father’s grave marker is also there. I’ll be glad to send a picture of the marker if wanted.

drobertson@nc.rr.com