Rebels Down Under: Part Two

We are pleased to welcome back guest author, Dwight Hughes.

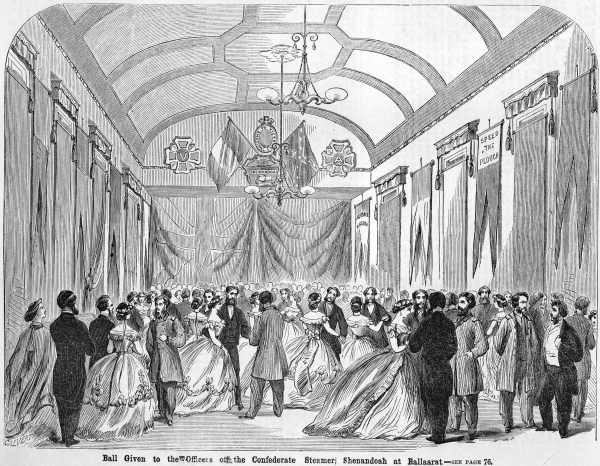

Despite pro-Yankee sentiments in Melbourne, the preponderance of sympathy was for the South, echoing the feelings of many in Great Britain. Conspicuous in gray uniforms, Shenandoah officers were approached on the streets, showered with social invitations, presented free open tickets by the railway company, voted members of the cricket club and of the prestigious Melbourne Club, and invited to attend the theater gratis. A visit was arranged to Ballarat, one of the principal mining districts in the hills above Melbourne with a tour of the mines followed by a sumptuous dinner and an evening ball. All of these activities occurred with enthusiastic participation of local elites making the Southerners comfortable in their proper milieu.

Officers in town visited the legislative assembly during a discussion on tariff where they excited much attention from members of the house and public gallery. By special invitation, several others attended a performance at the Theatre Royal of Othello starring the famous Barry Sullivan. Midshipman John Mason of Virginia thought the theater crowded and the performance miserable. During the intermission, the band struck up “Dixie.” Many in the audience cheered while some contributed hisses and groans, “all of which was excessively annoying to ourselves….” He departed at the earliest opportunity and returned to the ship.[i] On one Sunday, Midshipman Mason and Lieutenant Scales visited a little chapel called St. Peters just behind the Parliament House. It was the first time Mason had heard the service of the Church of England and it reminded him of a Sunday afternoon at the Church of the Holy Cross in Troy, N.Y. The building was plain and nice, he thought. They were shown into a pew with two young females who were “not at all pretty” but very civil and offered them a prayer book. “The ‘honest’ Melbourites stared at us with gaping mouths & starting eyes, as if they were astonished most amazingly to see two of the ‘Piratical gentlemen’ in the house of God.” Scales declared that the sermon was “excessively stupid” and could scarcely keep awake; Mason found it ordinary.[ii]

Why such excitement about the Confederacy? One factor was a strain of anti-Americanism with lingering resentment over the Revolution only eighty years past, along with Yankee stereotypes very like those expressed by Confederates.

One correspondent to the Age ascribed the acrimony to resident Americans having northern sentiments who, being suppliers of so many articles of daily consumption, feel free to dictate their opinions to local citizens. The North is merely trying to conquer the South, he continued, for the cotton Yankee merchants required while the South is engaged in a war of independence. “The only stain upon the South is the curse of slavery and this would be abolished before long.[iii]

“And can anyone help admiring the gallant stand the South has made? Did we not admire the Italians? Did we not admire the poor Poles? We did not assist either; but may we not admire?” And finally with reference to Shenandoah’s mission, Yankees reaped a great deal of glory from practicing the same treatment upon British merchants in two previous wars, but, “smart terribly now that they feel the lash themselves.”[iv]

The Melbourne Argus dismissed opposition arguments as “bunkum” reflecting Yankee character and institutions, not the true sentiments of the community. The Washington government was characterized by mismanagement, divided counsels, boastful language, and political corruption. It was a vulgar tyranny, “which has kept no faith with her enemies and…has broken every promise to its friends.”[v]

Under the pretext of a crusade against slavery, continued the editors, the United States, “has committed crimes against civilization more detestable than any slavery.” Eighty years previously in America, rightful rulers had been despised and rebels honored; now rebels were traitors. As insistently argued by Southerners, why shouldn’t the Confederacy do to the United States what the colonies had done to Great Britain? These were natural rights of revolution, freedom, and consent of the governed.[vi]

But enthusiasm for the South also was genuine and positive. The government of Jefferson Davis, noted one Briton, “spoke little and hit hard, came forth calm in adversity and modest in success, kept its eye fixed on its purpose, and strode towards it with resolute step.” Unlike Washington, Richmond behaved with, “dignity, a stern and haughty countenance, a quiet air, absence of ostentation and brag.” The English were more inclined to advocate a bad cause defended in proper form than a good cause badly defended.[vii]

Prime Minister Palmerston once remarked to a Confederate representative: “The common idea of England is that the Southern people are more like us in character than the Yankees, who have too much of the old Puritan leaven in them to suit us. You Southerners we consider only as transplanted Englishmen of the old stock.”[viii]

Many believed the South was fighting with fortitude and resolution for freedom under men cut from the same cloth as Washington and Jefferson, paragons of military genius, courage, patriotic valor, and sacrifice—men like the aristocratic Jefferson Davis (and in obvious contrast to a bumbling frontiersman from Illinois). Lee ranked with Wellington among the great generals of English blood. The death of Stonewall Jackson caused an extraordinary outpouring of grief. Victories of the Alabama were greeted with cheers in the House of Commons.[ix]

Lord Acton wrote to Lee complementing him for fighting the battles of English freedom and civilization, and concluded: “I morn for the stake which was lost at Richmond more deeply than I rejoice over that which was saved at Waterloo.” A cause fought for so valiantly by such men must be a just one. Tribute paid to Captain Waddell and his officers in Melbourne, concluded one editorial, was due to their patriotism and to their country’s chivalry.[x]

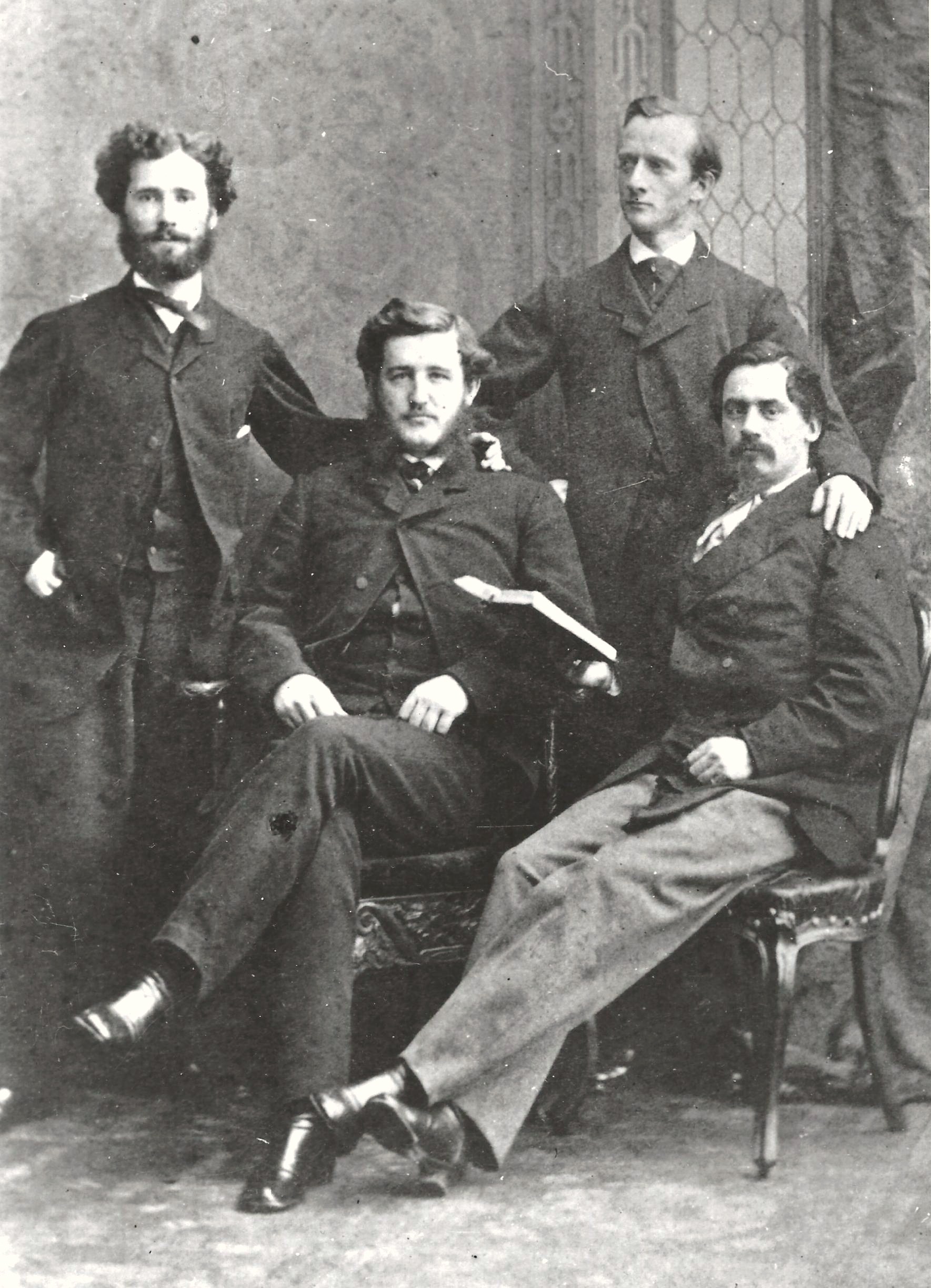

Waddell and his officers were invited to a sumptuous dinner at the Melbourne Club with sixty prominent government, civic, and business leaders. Two toasts were offered: “the Queen,” and “the Captain and officers of the Shenandoah, our guests of the evening,” followed by three cheers. Although the toast notably omitted reference to the Confederacy, the cheers were unprecedented as they were forbidden by rules of the club. To the relief of all concerned, Waddell was not asked to address the assemblage. It would have been embarrassing for all present had he spoken in defense of the cause, which he would have been honor bound to do if called upon. But the gathering inflamed the controversy anyway. The editor of the Age was enraged that government representatives and leading judges—“soft headed flunkeys” he called them—committed an egregious violation of neutrality.[xi]

Waddell was there to injure Australian commerce, the editor maintained, with the aid of British subjects who have been induced to become buccaneers. Was Shenandoah a joint stock speculation whose only object was plunder? Was the mercantile community insensible the injury which would result when American privateers swarmed the coasts, interrupting foreign intercourse? Merchants and traders should join in government efforts to get rid this interloper, rather than supplying him with coal and provisions to be paid for out of booty seized upon their coasts.[xii]

[i] James T. Mason, Journal, Eleanor S. Brokenbrough Library, Museum of the Confederacy, Richmond, VA. (not paginated), 2 March 1865.

[ii] Mason, Journal, 18 March 1865.

[iii] Melbourne Age, 27 January 1865.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Cyril Pearl, Rebel down under: When the ‘Shenandoah’ shook Melbourne, 1865 (Melbourne: William Heinemann, 1970), 41-42.

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] Sheldon Vanauken, The Glittering Illusion: English Sympathy for the Southern Confederacy (Washington, D.C.: Regnery Gateway, 1989), 62.

[viii] Howard Jones, Blue & Gray Diplomacy: A History of Union and Confederate Foreign Relations (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010), 158.

[ix] Vanauken, The Glittering Illusion, 69, 100, 101.

[x] Ibid., 103; Pearl, Rebel Down Under, 42.

[xi] Melbourne Age, 1 February 1865.

[xii] Ibid.