Thoughts on Appomattox (part five)

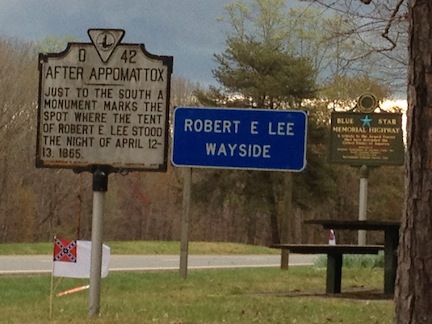

On the night of April 12, as he made his way back to Richmond after leaving the remnants of the Army of Northern Virginia, Robert E. Lee pitched his camp alongside the road. Today, the spot—along modern route 60 midway between Dillwyn and Buckingham—is marked by a few historical signs and a small monument. Small Confederate flags flutter around each monument, sign, and marker like daffodils that have sprung up for the surrender.

On the night of April 12, as he made his way back to Richmond after leaving the remnants of the Army of Northern Virginia, Robert E. Lee pitched his camp alongside the road. Today, the spot—along modern route 60 midway between Dillwyn and Buckingham—is marked by a few historical signs and a small monument. Small Confederate flags flutter around each monument, sign, and marker like daffodils that have sprung up for the surrender.

How did Lee feel that evening, after he’d retired to his tent?

Does the gut punch of defeat keep him awake? Does he feel relief that his desperate flight is over? Disappointment that he failed his men? Has exhaustion finally caught up with him and pulled him into a deep, deep sleep? Or is he restless?

Is he heartbroken? Is he deflated? Is he resigned? Is he embarrassed?

Is he looking forward to just being home, finally, after all these years? Is he anxious to see his wife? Anxious to hide away?

Lee has become so mythologized, so marbleized, over 150 years that it’s sometimes hard to remember how human he was. We see him as military leader–but forget to see him as a man.

So duty-bound was he that he often subsumed his own emotions and opinions. One hundred and fifty years later, it’s often hard to see how he felt at any given time–but his actions always demonstrated what he knew to be right.

So duty-bound was he that he often subsumed his own emotions and opinions. One hundred and fifty years later, it’s often hard to see how he felt at any given time–but his actions always demonstrated what he knew to be right.

But now right and wrong had been redefined compared to his old world order—decided on the battlefield, a venue the professional soldier in him recognized as absolute. Had he yet started to wonder Now what?

He threw away his entire career and turned his back on the opportunity to lead the entire Federal army, for a cause he felt was right: the defense of his home, Virginia. His duty kept him away from his wife and children for years at a time. We look back on that and see it through the same lens he did: that of duty.

Did it all seem for naught?

In a letter he wrote to Confederate President Jefferson Davis on April 20, Lee revealed that he’d already seen the handwriting on the wall prior to the collapse of the army.

“The operations which occurred while the troops were in their entrenchments in front of Richmond and Petersburg were not marked by the boldness and decision which formerly characterized them,” he wrote. “Except in particular instances, they were feeble, and a want of confidence seemed to possess officers and men. This condition, I think. was produced by the state of the feeling in the country, and the communications received be the men from their homes, urging their return and the abandonment of the field.”

Did he feel embittered? Betrayed? Resigned?

Had these thoughts even gelled by the time he took his leave from the men of his former command?

As he sat in his tent, how did he feel?

Much delayed reply to a topic of great interest to me. No clear answers. I used Freeman’s RE Lee V4,C.X mostly. Taylor, Marshal, Venable and GB Cooke all started with Lee on 12 April but Venable and Cooke left group on 12 &14 respectively. Cooke’s Just Before and After Lee Surrendered to Grant (from his diary& discussion with Freeman!) could be a treasure (if located). Freeman & others describe Lee on 12-15 (arrival in Richmond) as an “extremely grave and dignified gentleman who was weary and care-worn,whose face showed self-respecting grief, majestic composure, rectitude & sorrow, whose emotions (were)strained almost to tears…(yet who was) not willing to keep alive ill-feeling.”

Lee, himself, left no written ‘personal feelings’.