A Reexamination of “The Unique Style Confederate Hat”

Today, we are pleased to welcome back guest author Drew Gruber

As students of Civil War we are excited when ‘new’ objects surface which add character, detail and color to our overall narrative. It is especially exciting when these objects challenge the accepted forms and values, giving us pause to reexamine their provenance and details against extant artifacts and primary source material. A hat, known simply as “Unique Style Confederate Hat” in the Texas Civil War Museum warrants just that closer examination as a truly exciting and distinctive artifact.

The Texas Civil War Museum acquired the hat in 2006 from a private collector. The artifact arrived with little documentation or provenience, except a small tag pasted to the hat’s body which reads “From Big Round Top, Gettysburg Battlefield.” This tag is pasted on top of another label obscuring all of the words except “Captured” and “Gettysburg.” Handwritten labels, simply pasted onto the objects are indicative of the late 19th and early 20th century curation of private collections or ‘curios.’ Similar labels appear on other Civil War artifacts collected from soldiers and early battlefield tourists.

While the hat cannot be attributed to any single soldier, its distinctive design offers clues which can be used to help trace its history. As pictured the hat is clearly unique from other identified Confederate headgear such as the infamous “slouch” hat or the European inspired “kepis” most associated with Civil War soldiers. When compared to other hats, caps, images and primary sources this artifact’s characteristics begin to offer up clues as to its origin.

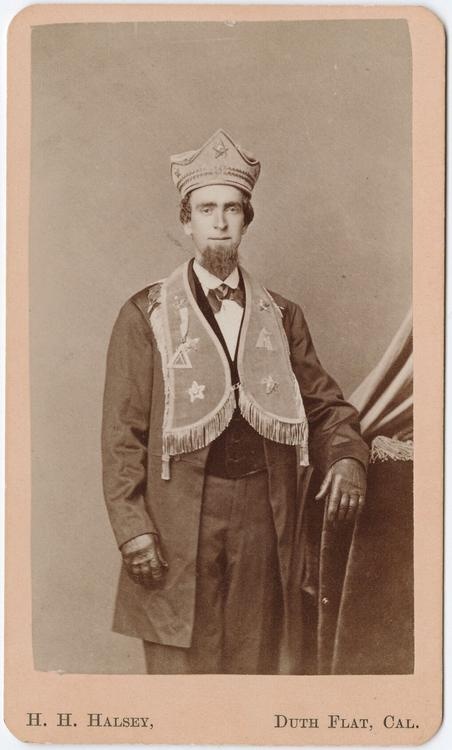

The body of the hat appears to be made of white fabric applied over a pasteboard- not like traditional felt and it obviously does not have a brim. A transition between the interior lining and the exterior body was done with a cord- known as cording or welting. The crown or in this case the “bag” is made of a fabric (potentially cotton) draped over the side of the body, which culminates with a metallic tassel. This is similar in the fashion to the ‘Sicilian’ caps worn by soldiers early in the war and is also similar to a fez, worn by Zouaves. The body is trimmed on the bottom and top exterior with metallic tape or trim and has a large five point metallic star on the front. It makes for a foppish garment but one which does not seem geared towards all weather use.[1]

The use of large single stars on uniforms and accessories was not limited to any one state in the Confederacy, nor to the Confederacy as a whole but is more often associated with Southern troops. Photographs and other period references illustrate the use of metallic stars on hats, jackets and other equipment regardless of a soldiers rank or branch of service. When surveying contemporary photographs, Texas and Mississippi troops are most often seen with a single star emblazoned on their headgear. In this vein the Texas Civil War Museum has placed an exhibit tag alongside the hat stating where it was found and that, “… (it) probably belonged to a Mississippi soldier.”[2]

The State of Mississippi mentions the use of stars as symbols for officers and enlisted men in their clothing regulations. Metallic gold stars were to appear on the collars of officers or on their shoulder boards, while enlisted men were ordered to wear white stars on the collars of flannel fatigue shirts. [3] A single star-a symbol long associated with Texas does not appear in the specific uniform guidelines for that state. However, pre-war Militia Uniform Regulations comment that a “Texas Star” was to be worn on the front of the headgear. These regulations while not always adhered too, created an esprit de corps or unique unit designator. [4]

Decorative stars shown adorning uniforms sometimes weren’t regulatory at all. Valerius Cincinnatus Giles who enlisted in the Tom Green Rifles, soon to be part of the Fourth Texas was posing for a photo in a large black hat when he commented, “While Bridges was placing me in position for this ambrotype, he suggested that I would look more fierce and military if I would pin one side of my hat back with a star. He had a supply of stars on hand which he sold for a dollar a piece.”[5]

If the hand written label(s) on the hat in the Texas Civil War Museum is authentic and reliable it helps answer the question of the hat’s owner by narrowing the list of possible Confederate troops who were in the Big Round Top area during the Battle of Gettysburg. According to both primary and secondary sources, the majority of the Confederate troops deployed in Big Round Top on 2 July 1863, hailed from Alabama and Texas. This information when combined with the hats design may help narrow its context even further.

By combining the hat’s label, uniform trends, regulations and photographs against the Confederate order of battle for Gettysburg; a case is made for it being worn by a Confederate soldier, potentially a Texan during the intense combat on 2 July 1863..

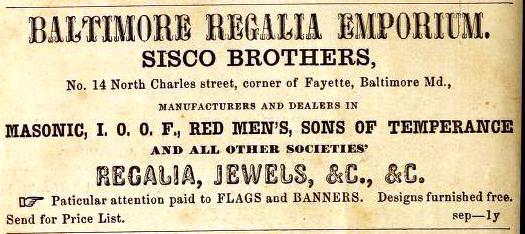

Until recently, no other extant hat has shown similarities in construction techniques, materials and design. However, in early 2013 a series of hats labeled, “Sisco Brother, Regalia Manufactures, Baltimore MD” appeared on Ebay. These hats have striking similarities to the hat in the Texas Civil War Museum including the chosen materials, color, patina, general design and ornamentation. Their construction details also include a ‘bag’ crown, corded edges and similar stars and trim. This uncanny similarity warrants a closer look into “Sisco Brothers” and their wares.

The E.M. Cross & Co. Baltimore City Directory for 1863-1864 is the earliest known public advertisement for the “Sisco Brothers.” They were listed as “wholesale and retail manufacturers of odd fellows and masons regalia, military goods, baxters, flags, signals, gold and silver fringes, gimps, tassels, &c…”[6] By 1865, Wood’s Baltimore City Directory has them advertising regalia and ladies dress trimmings. In Richmond, Virginia by 1868 the Southern Planter& Farmer had a listing for “Sisco Brothers” advertising for flags, banners and society regalia.[7] Subsequent post war advertisements through the 1920s include myriad items from swords, hats and flags to ribbons and temperance regalia. Extant “Sisco Brothers” items include swords, hats, flags and Confederate union ribbons and buttons.

When compared to those “Sisco Brother” hats which recently surfaced the ‘Unique Style Confederate Hat’ beings to look less similar to extant Civil War headgear. In fact removed from the potential Confederate context the hat on display at the Texas Civil War Museum does resemble post war reunion paraphernalia including extant odd fellows, Masonic and other societal hats. Though Sisco Brothers is contemporary to the conflict it is not known if they took on any quartermaster contractors or sold their wares to places where a Texas or Mississippi may have procured such a hat. However, their heavy sales of reunion and regalia items during the post war period leads historians to wonder if they catered to any Gettysburg reunions or sold merchandise to the myriad souvenir stands in Devils Den and at the Round Tops.[8]

Upon acquisition in 2006, the Texas Civil War Museum’s “Unique Style Confederate Hat” was truly unique to the Civil War community and it wasn’t known that similar objects would come to light in the future. Thus, the beginning of the article seeks to reinforce the current interpretation of the “Unique Style Confederate Hat” utilizing the hats forms and values which are supported with contemporary resources. In comparison, the second half of the article suggests an alternative; that the hat on display is a post-war piece which is indicative of reunion and fraternal regalia. Whether it flew from the head of a Texan charging into the maelstrom on July 2nd 1863 or was purchased by an arthritic veteran carefully making his way through a reunion crowd decades later this truly unique style hat reminds us of the humanity persistent in every detail of the Civil War.

This article would not have been made possible with the help and encouragement from Cynthia Harriman and Ray Richey of the Texas Civil War Museum. They provided the photographs, permission and encouragement for this study. Additionally, I would like to thank Jay Howlett and Greg Starbuck who provided invaluable insight into the construction of mid nineteenth century headgear.

.

Notes

[1] Conversations with Jay Howlett, Artificer, Department of Historic Trades, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation as well as Gregory Starbuck, Executive Director of Historic Sandusky and professor of History at Lynchburg College. January 2014.

[2] Conversation with Cynthia Harriman, Executive Director, Texas Civil War Museum. January 2014.

[3] Orders of the military board of the state of Mississippi; printed by order of the military board. Jackson, MS: State Printers, 1861. http://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/010944203

[4] Ron Field. American Civil War Confederate Army. Brassey’s History of Uniforms. London: Brasseys, 1998.

[5] Valerius Cincinnatus Giles, Rags and Hope. Edited by Mary Lasswell. New York, NY: Coward-McCann Inc, 1961. Page 24.

[6] E.M. Cross & Co.’s Baltimore City Directory. Edited by Henry R. Hellier. Baltimore, MD: E.M. Cross & Co., 1863. Page .156 https://archive.org/details/emcrosscosbaltim1863emcr

[7] Southern Planter & Farmer. Edited by Ch. B. Williams. Richmond: VA, October 1868 https://archive.org/details/southernplanterf2910sout

[8] Conversations with Jeffery Hunt, Director of the Texas Military Forces Museum as well as Garry Aldeman, Education Director, Civil War Trust. January, 2014.

Hi, I found reference in the Baltimore Daily Exchange for the partnership Sisco Brothers being formed May 4 1861, before that it was A Sisco. Both store and factory were at 95 W Baltimore opposite Holliday, according to the ad. Their trade was dress trimmings, regalia and, most appropriately military goods. A Cisco was also manufacturing military goods back in 1858. I wonder whether a soldier who was a mason or oddfellow might choose military headwear that signified or hinted at his lodge membership — even in the vain hope that it might save his life if the Union soldier coming at him with bayonet fixed might be a mason too…

Leave it to the Confederates to wear such silly headgear!

What an article. I can’t help but thinking, however, of the tales of Confederates marching into Pennsylvania and “trading” their tattered headgear for anything and everything worn by the locals.

Joel Manuel

Baton Rouge