Remembering Stoneman’s Raid in the Chancellorsville Campaign

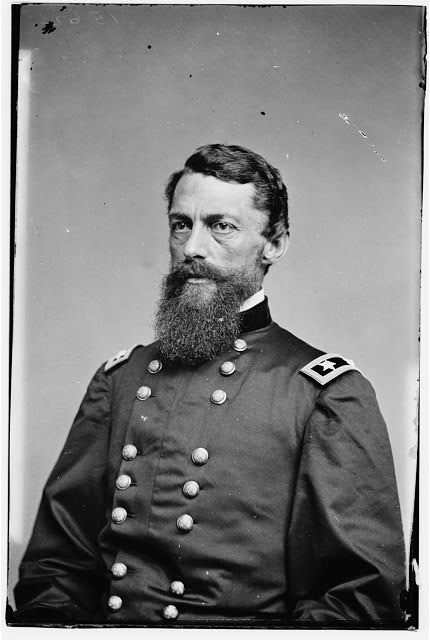

Today marks the 153rd Anniversary of the beginning of Stoneman’s Raid. After weeks of delay due to poor weather, Stoneman’s troopers began crossing the Rappahannock at Kelly’s Ford. Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker intended for Stoneman’s cavalry corps to wreak havoc on the Confederate rear and upset enemy logistics. Hooker hoped this manuever would force Gen. Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia to abandon his position at Fredericksburg and withdraw south to protect his lines of communication. This would open the way for Hooker to pursue the retreating Confederates and trap them between his infantry and cavalry somewhere between Fredericksburg and Richmond. Unfortunately for Stoneman, the plan did not shake out as his chief envisioned.

Lee did not bite at the worm on the line. While Stoneman’s troopers fanned out across central Virginia in individual raiding columns, Lee engaged and defeated Hooker west of Fredericksburg in the Battle of Chancellorsville. Without official word from Hooker of his movements, Stoneman, with part of his command returned to the Army of the Potomac. He reached the safety of Union lines on May 8.

It was not long before Hooker started to shift responsibility of the defeat to his subordinates rather than account for his own failure. Despite his assignment, Stoneman was not on hand to assist Hooker at the moment of crisis. This was enough to draw blame from Hooker. On May 15, Stoneman took a leave of absence. He never returned to the Army of the Potomac. His contributions, however, remained.

Combined with the Battle of Kelly’s Ford in March, the expedition was a major morale boost to the men of the cavalry corps. This new found confidence in their fighting abilities continued to grow in June at the Battle of Brandy Station and served the corps well in the months and years to come.

Stoneman’s Raid was also a step in the transition of the corps. The cavalry was beginning to shift from their traditional role of screening and reconnaissance to one of a mounted strike force with the primary objective of locating and engaging the enemy. Further, it showed the Union high command that the corps was capable of operating independently in enemy territory without infantry support and away from its base of supplies. The expedition provided a foundation for future operations such as the Kilpatrick-Dahlgren Raid, the Wilson-Kautz Raid, Phil Sheridan’s raids in the spring and summer of 1864.

Stoneman later transferred to the Western Theater where he continued to ply the trade he learned on his first raid in Virginia. After the war, he served as Colonel of the 21st U.S. Infantry. He retired in 1871 and was elected for a term as California’s governor. He passed way in Buffalo, New York in 1894.

A lot of things had to go wrong for Hooker to lose that fight. And they did.

They did indeed. What is unfortunate is that as a cavalry officer Stoneman was head and shoulders above his successor Alfred Pleasonton. When an officer at any level is replaced, it is done with the mindset that the new commander will perform better than their predecessor. That was not the case with Pleasonton and I don’t think it was very long before Hooker realized that privately.

Although, if I recall correctly, Stoneman was not at his best in those pre-Preparation H days.

His raid in Georgia in the summer of 1864 when he is captured certainly is not his finest hour. I think his time as a quartermaster for the Mormon Battalion during the Mexican War was beneficial. It gave him some insight into administration and organization, which I think were his most vital assets. Unlike Pleasonton, I think Stoneman understood the need and value of timely reconnaissance and accurate intelligence.

Stephen Sears’s book on Chancellorsville is very critical of Stoneman, implying very strongly that if he had achieved his objectives, Hooker’s overall plan (which Sears thought was well-thought-out) would have worked. Comment?

Sears is the great Hooker apologist. His work goes out of its way at times to point fingers, unfairly, at both Stoneman and John Sedgwick. Howard was useless as a bag of wet-hair as a corps commander in the east, and a dolt to boot. The blame placed upon his shoulders was justified, though the men under his command didn’t deserve much of what was hurled at them. Their upper echelon commanders failed them.

Hooker’s plan was pretty solid on paper, the execution was thoroughly flawed.While we will never know the truth (Hooker never told us the truth of his plans after the battle), it seems as if he was banking on Lee fleeing the Fredericksburg area, rather than standing and fighting it out. While Hooker talked a big game about destroying Lee, and he had plenty of opportunities to do just that throughout the entire battle, he became hamstrung when Lee would not stick to Hooker’s initial plan.

When the plan was in the early execution phase, Hooker misused both Stoneman’s troopers, and Sedgwick’s Left Wing, over and over again.

Stoneman was too slow to get the ball rolling and then when Mother Nature reared her ugly head, compounded his problems. The reality of the situation is that Hooker was too bold in ordering Stoneman’s cavalry so far south, too faraway from the main area of operations. (Which lends credence to the idea that Hooker anticipated Lee’s withdraw from the area). Hooker also failed to keep enough cavalry with the main army, one brigade was not enough at the crossroads. These men could not properly screen and scout for the main army. At the Fredericksburg Sector, handful of companies were not enough to support Sedgwick’s wing either.

While Stoneman’s men did some light damage to the Confederate rail lines and communication lines, much of what they had “destroyed” was repaired by May 7.One day after the campaign officially closed. In fairness to Stoneman, where was Lee’s retreating army? Part of his job was to harass and slow them as the retreated to defend Richmond. By not pressing his advantages, and not pressing Lee out of the Wilderness, 10,000 or so troopers were on an extended ride. Thus, Hooker took one key piece of his army off the board himself, allowing Lee, Jackson, and Stuart to have their way with Hooker. When one of Stoneman’s division’s arrives back on the battlefield, on May 2 (Averall’s division), they are not put to use at the front by Hooker, rather, they are in the rear at Ely’s Ford. Stuart then humiliates him by leading a very short lived raid on the Averall, just after Jackson’s wounding. The next day, rather than using Averall’s men as he should have, Hooker decided to have many of them dismount and file in behind his failing lines at Fairview and the crossroads. They were to make sure that no unhurt man went to the rear. They were put on provost detail, rather than screening the army or striking Stuart’s or Lee’s infantry corps’ in the flank.

Hooker has no one to blame but himself, and O.O. Howard for his loss at Chancellorsville. Sedgwick gave Hooker no less than three opportunities to turn on Lee’s army. Stoneman’s men needed a few extra days to get out and start impacting the campaign, his circuitous route, and some lack luster subordinates, hampered his impact.

Regardless of what Hooker says, Stoneman was not at Cville on the evening of May 2nd and morning of May 3rd, when, the Confederate army was sitting in two distinct pieces, numbering less than 45,000 men-while Hooker had some 80,000 to throw into the fray. (Don’t buy the hype that Jackson’s flank march was a stunning success, it actually left Lee in a very bad position on the evening of May 2 and into the 3rd)/ Hooker could have destroyed Lee and Stuart in two separate engagements, in two separate pieces. Nor was Stoneman there when Sedgwick took Marye’s Heights and threatened the Confederate rear. Again, Lee split his army, weakening it after two and a half days of vicious fighting, and Hooker could have fallen on Stuart at the crossroads, and crushed what remained of Lee’s forces near the Salem Church. The Federals still had nearly two full corps that were not enegaged, while Lee placed all his cards on the table. Hooker may have been “wounded” at this time, but his lackluster staff, and a second-in-command lacking the testicular fortitude to relieve a wounded army commander, doomed the AoP.

In the end, no substantial reinforcements arrived to help Lee from the Richmond or Suffolk area. The campaign was so short that Stoneman’s impact on Lee’s supply line was negligible at best, and Lee never fell back towards Stoneman’s troopers to allow them to really play an active role in the fighting. Just like Lee lost the battle of Gettysburg, Hooker lost the battle of Chancellorsville. It was Hooker’s decisions and indecision’s that cost the AoP in the end. Oh, and Howard. That guy was an idiot.