Mexican-American War 170th: Fort Brown Gets Its Name

On May 17, 1846 Brig. Gen. Zachary Taylor, pausing to reflect in the wake of his army’s victories against Mexican forces, published General Orders No. 62. “In memory of the gallant commander who nobly fell in its defence, the field-work constructed by the labor of the troops opposite Matamoras will be known as ‘Fort Brown,’” Taylor’s order began.[1]

As American forces returned to the Rio Grande in the wake of the battles of Palo Alto and Resaca de la Palma, they saw the fort’s garrison, left behind to defend the position as the main army marched to Point Isabel. An officer in the 3rd Infantry commented that “The defenders of the fort have suffered every thing; they have been harassed night and day, and all looked haggard from the want of sleep.” The returning troops were left to ask what happened here?[2]

When Zachary Taylor learned that his supplies at Point Isabel were being threatened by Mexican forces, he quickly marched out to intercept his foe, leaving behind in the fort the 7th Infantry and two artillery batteries, one from the 2nd Artillery, and one from the 3rd. In total, Taylor behind “about 500 men,” all under the command of Maj. Jacob Brown, who commanded the 7th Infantry.[3]

At first, duty at the fort continued on its mundane course. On the day that Taylor departed, 2nd Lt. Napoleon J.T. Dana wrote to his wife that he and the fort’s other defenders “Sleep in clothes all the time, and always on the alert,” but Dana was confident that nothing serious would happen. “All will go well and I trust soon that your dear little heart will be eased by good news of us.”[4]

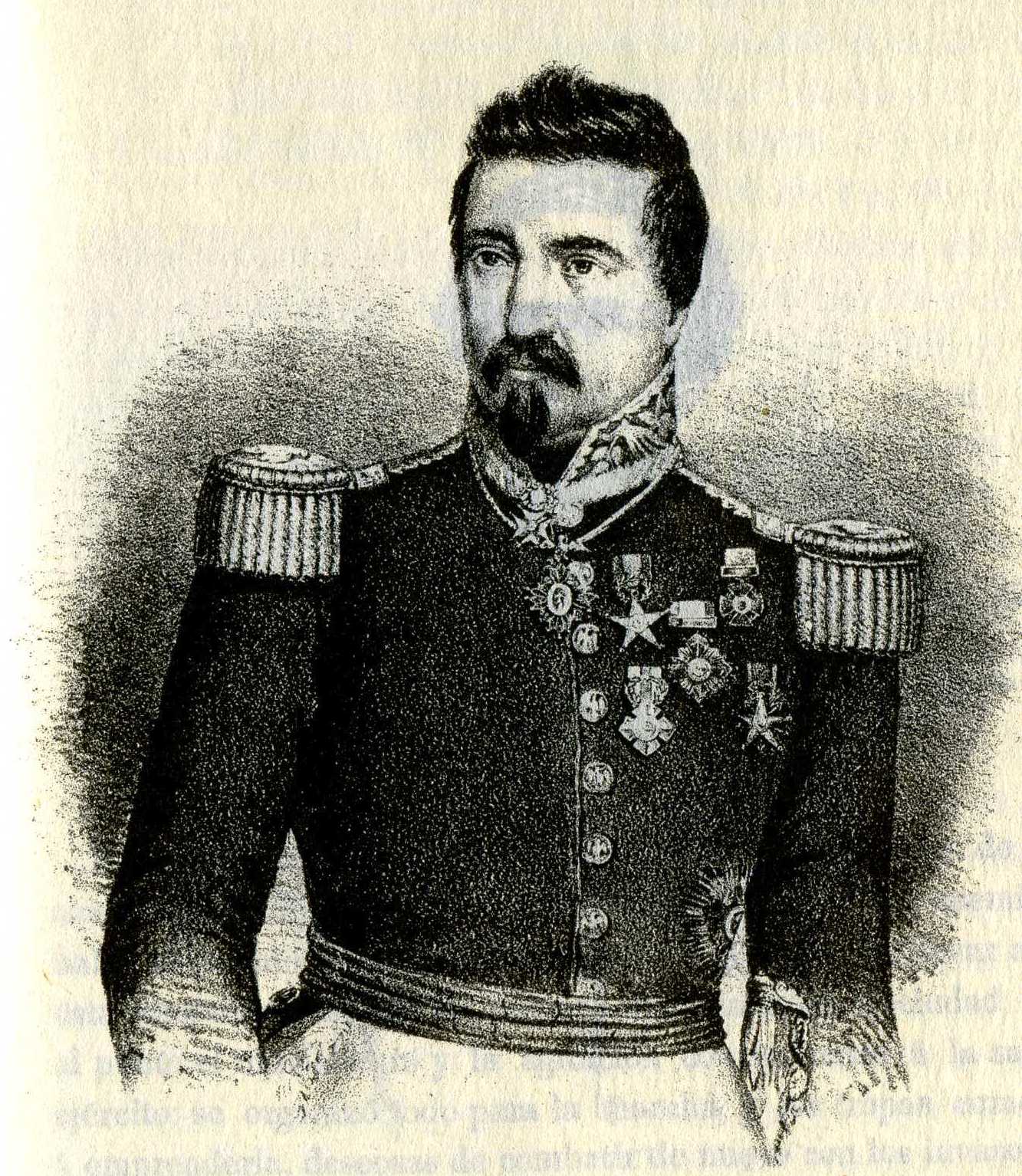

For one day, Dana’s assumptions of quiet continued, but then, at first light on the third day of Taylor’s departure, May 3, all hell broke loose. Gen. Mariano Arista, in command of the Mexican forces along the Rio Grande, planned a one-two punch that would, he hoped, knock Taylor off of the river and force the Americans to retreat. While Arista commanded the main contingent of his forces that chased Taylor, he too left behind a force along the Rio Grande. Left behind in Matamoras, some 1,600 men under the command of Gen. Francisco Mejía would besiege the fort, and if all things went according to plan, would knock out Brown’s garrison while Arista defeated Taylor.

Mexican cannons roared from the south side of the Rio Grande on the morning of May 3. Lt. Dana wrote, “their shot and shells began to whistle over our heads in rapid succession. They had commenced in real earnest, and they fired away powder and copper balls as if they cost nothing and they had plenty of ammunition.”[5]

The American gunners jumped to their own pieces and began a steady return fire. Inside the fort, Brown had 8 artillery pieces. Half of them, from Cpt. Allen Lowd’s 2nd Artillery, were large 18-pounders and the other half, from the 3rd Artillery, were lighter 6-pounders commanded by 1st Lt. Braxton Bragg, who would go on to command the Confederate Army of Tennessee.[6] With adrenaline pumping, the Americans made use of their smaller complement of artillery and began a steady fire on Matamoras. The heavier shot of Lowd’s 18-pounders soon destroyed two Mexican cannons, but the American elation with their success soon subsided as they were unable to destroy any other guns.

About a half hour into the engagement, Brown lost his first man. Sergeant Horace Weigart, 7th Infantry, stood on the fort’s bastion in case of a Mexican infantry attack. As he stood to, a piece of grapeshot “struck him in the chin, came out of the back of his head, and he fell on his face down the banquette, dead,” Dana wrote. Soldiers brought Weigart’s corpse to the fort’s hospital, but the Mexicans were not finished with Weigart. The corpse “had not lain there an hour before a shell from the enemy’s battery carried his head off, looking as if they had a special spite against that particular man,” Dana added. Gruesome as Weigart’s demise, American soldiers hunkered closer to their fortifications, hoping to avoid the same fate.[7]

The bombardment continued into the afternoon, but Brown first “ordered a deliberate fire,” and then, later, after realizing his shots weren’t accomplishing much “and wishing to husband our men and means, I ordered the fire to cease and the guns posted to repel an assault from the rear.” While Brown paid close attention to his 8 guns, he also ordered his infantry to continue work on the unfinished fort, strengthening the approaches and thickening the walls.[8]

With the Americans holding their fire in case of an infantry attack, Mexican guns continued to throw ammunition at the American fort. On May 5, Gen. Pedro de Ampudia, Arista’s second-in-command, arrived with reinforcements to strengthen the Mexican line and continue building pressure.

Inside the fort, American soldiers found whatever protection they could. Captain Daniel Whiting from the 7th Infantry wrote that “The whole interior was plowed and furrowed by exploding bombs, dug up and piled in heaps and ridges, amid spattered rubbish and bursting baggage. Tents riddled by shots and shell were in tattered ruin, while the torn parapets and ragged embankments testified to the vindictiveness of the siege.”[9] But through the fire, one woman, Sarah Borginnis [or Bowman, depending on the source] continued her duties as a camp follower—cooking meals, tending to the wounded, and distributing water to the besieged forces. After the siege, Braxton Bragg toasted Borginnis, saying, “during the whole of the bombardment the wife of one of the soldiers, whose husband was ordered with the army to Point Isabel, remained in the fort, and though the shot and shells were constantly flying on every side, she disdained to seek shelter in the bomb-proofs, but labored the whole time cooking and taking care of the soldiers, without the least regard to her own safety. Her bravery was the admiration of all who were in the fort, and she has thus acquired the name of ‘The Great Western.’”[10]

On May 6, the third day of the siege, Brown fell. A Mexican howitzer shell exploded and “took off the leg of Major Brown below the knee.” Amputation followed, but as the siege continued, Brown’s wound became infected and he died on May 9 “even whilst he heard [Taylor’s] cannon pouring death among the enemy whilst marching to our relief [the Battle of Resaca de la Palma].”[11]

Thinking the Americans were broken down because of their infrequent return-fire, Gen. Ampudia called for a cease-fire and demanded the fort surrender. Captain Edgar Hawkins, having taken command of the fort after Brown’s wounding, called a council of war and soon replied to Ampudia with a dash of humor, “That we had received his humane communication, but not understanding perfectly the Spanish language, we were doubtful if we had understood exactly his meaning; but from all we could understand, he had proposed that we give him possession of this place or we would all be put to the sword in one hour; if this was proper understanding, we would respectfully decline his proposition, and ‘took this opportunity to assure his excellency of our distinguished consideration.’” After the Americans’ refusal, Ampudia opened fire once more.[12]

But as hard as he tried, Ampudia could not knock down the fort’s walls. With the large 18-pounders and 6-pounders waiting to repulse any attack, Mexican infantry was hesitant to go forward, and so the ineffective artillery barrage continued. On May 8, the Americans could hear the Battle of Palo Alto, and in the wake of Arista’s defeat there, Ampudia was called to reinforce him the next day. Some Mexicans remained in position and continued firing, but the Americans could hear, on May 9, “the re-engagement between the armies.”[13] A few hours later, the fort’s garrison saw “quite a number of Mexican cavalry and a few infantry. . . in the retreat,” from Resaca de la Palma.[14] Arista’s second defeat brought the siege to a close as Taylor’s army closed in and reinforced the battered garrison.

Writing his official report to Taylor, Capt. Hawkins credited the troops of the 7th Infantry and 2nd and 3rd Artillery Regiments before closing, “We have only to lament the loss of a gallant and faithful officer, who, proud of the trust reposed in him, would have gloried in the accomplishment of the task in which he so gallantly commenced.”[15]

During the six-day affair, the Americans suffered two either killed or mortally wounded—Weigart and Brown, and ten wounded. They had been the target for some 4,500 Mexican artillery projectiles fired over the course of the siege. Picking up a piece of shrapnel, Capt. Dixon Miles, 7th Infantry, slipped it in an envelope and mailed it back to the east coast to be added to “a collection of curiosities” gathered by a Baltimore high school.[16] (Miles would be part of a much-larger, much more famous siege in 1862, when he was killed trying to defend Harpers Ferry from Stonewall Jackson.)

With Zachary Taylor’s General Orders No. 62, published today, 170 years ago, the bombarded defenses became known as Fort Brown. The fort became the center of Brownsville, the town expanding and enveloping what during the war years had been ransacked by thousands of screaming shots and shells.

The next day, May 18, Taylor’s forces crossed the Rio Grande and occupied Matamoras. He had not yet received the official declaration of war, but Zachary Taylor was now bringing the war to Mexico.

_____________________________________________________________

[1] Ex. Doc. 60, House of Representatives, Mexican War Correspondence, 489

[2] William S. Henry, Campaign Sketches of the War with Mexico, 103.

[3] Niles’ National Register, May 23, 1846, “Incidents of the Campaign.”

[4] Monterrey is Ours!: The Mexican War Letters of Lieutenant Dana, 1845-1847, Edited by Robert H. Ferrell, University Press of Kentucky, 1990, 58.

[5] Dana, 59.

[6] Niles’ National Register, June 6, 1846, “Further Details of the Battles On The Rio Grande.”

[7] Dana, 60.

[9] Douglas A. Murphy, Two Armies on the Rio Grande (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2015), 242.

[10] Niles’ National Register, July 4, 1846, “Toast to the Heroine of Fort Brown.”

[11] Dana, 61.

[12] Niles’ National Register, June 6, 1846, “Bombardment of Fort Brown.”

[13] Captain Edgar S. Hawkins’ Report, printed in Public Documents Printed by Order of the Senate of the United States, First Session of the Twenty-Ninth Congress, Vol. 8, (Washington: Ritchie & Heiss, 1846), 34.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Niles’ National Register, July 18, 1846, “Present of Exploded Shot by Capt. D.S. Miles to the Baltimore High School,”

Great story. On the site of old Fort Brown is an artillery piece, embedded upright in the ground, muzzle up. As far as I know it has never been positively identified, but my belief is that it makes the spot where Major Brown was mortally wounded. Here it is c. 1999:

https://deadconfederates.files.wordpress.com/2016/05/lookgun.jpg

Thanks for the comment and photo, Andy. I ran across the same second-hand source stuff about the cannon marking Brown’s mortal wounding spot. I couldn’t determine if it was 100%, so I decided to leave it out. Thanks again.

Interesting reading; thanks !

Thanks for reading David!

Ran across this interesting article today – wonderful story and information.

My great, great, grandfather was Capt Daniel Powers Whiting, 7th Infantry.