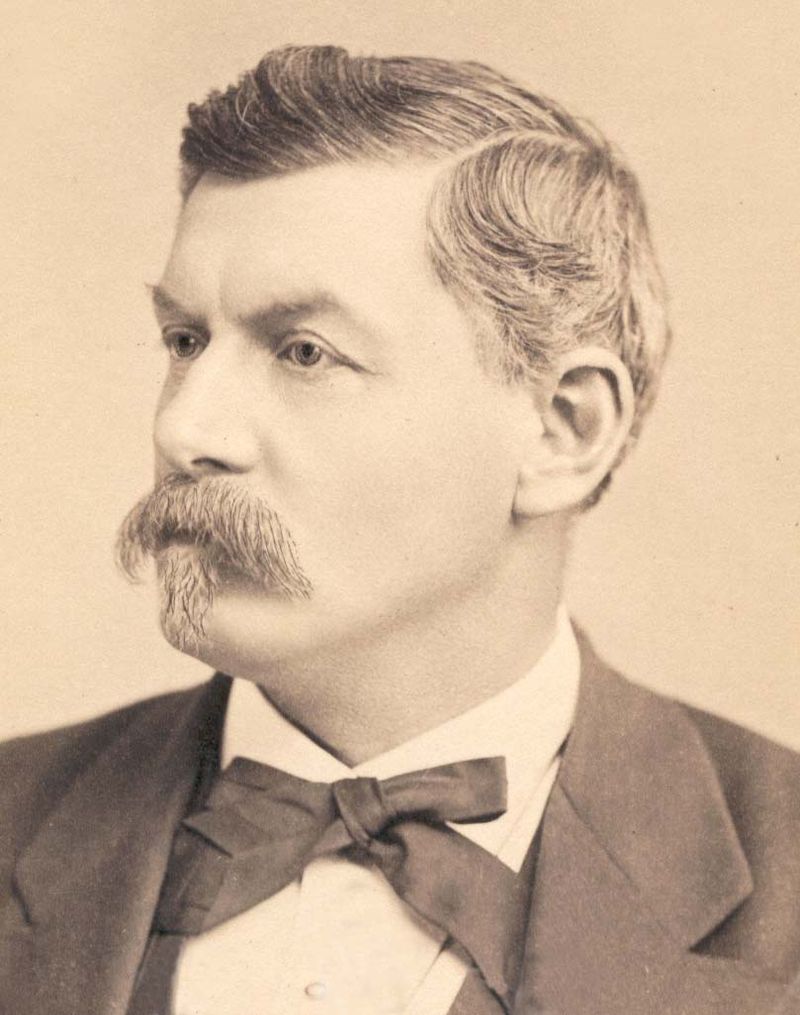

“Little Mac’s” Final Moments: The Death of George B. McClellan

Emerging Civil War is pleased to welcome back guest author William Griffith

“The startling announcement was made on Thursday [actually Friday] morning that General McClellan was dead,” read New Jersey’s The Orange Journal on Sunday, October 31, 1885, “…very few knew that General McClellan was in the least ill, and no one but his physician, perhaps, knew of the serious character of the disease that was afflicting him.” Less than a week before he had been seen riding in his carriage through West Orange in what was described as “the picture of perfect health.” Only days later, George Brinton McClellan, one of the Army of the Potomac’s most beloved and controversial generals was dead at the age of fifty-eight.[1]

Several weeks earlier at the beginning of the month, McClellan began complaining of chest pains that were originally diagnosed as nothing more than the effects of dyspepsia. The ailment subsided until October 18, when he called upon his personal physician, a “Dr. Seward,” complaining of more pain in his heart region while preparing to depart for business in Boston. Concerned that symptoms of actual heart trouble were now developing, Dr. Seward ordered McClellan to return home and rest so further examinations could be conducted. There he remained, passing the time at home by “reading, writing and conversing, or enjoying a drive in his open carriage through [East and West Orange].” There were no flare-ups of pain during that week and a half, and it was believed that his condition was improving from the rest and “quiet of the country.” Then on Thursday, October 28, things took a turn for the worse.[2]

The following is a description of McClellan’s final hours reported by The Orange Journal:

On Thursday evening … he was seized with pains in the region of his heart. The pain passed away and returned again with greater violence at 10 o’clock. At 11 o’clock Mrs. McClellan telephoned for Dr. Seward, and shortly after the Doctor received another telephone call requesting haste, and in thirteen minutes from the receipt of the first call, Dr. Seward was by the side of the sufferer. He was seated in his chair, and remedies were immediately applied which brought relief. The pains returned again, however, and Dr. Seward decided to remain with his patient. When the General felt better he was removed to his bed. The night was damp and foggy, and the windows were all closed, and the atmosphere of the room was somewhat heavy. A person with a heart trouble needs all the air possible, and the General was rather restless under the canopy which was adjusted over his bed to keep out mosquitoes. This may have produced a second paroxysm, for between two and three o’clock the pains returned, for the sufferer was removed to the chair. Mrs. McClellan and [their daughter] Miss [Mary “May”] McClellan were in the room the while, doing what they could. Restoratives were again administered, but the terrible pain only increased in violence, and at ten minutes to three o’clock, without a word of warning, the General placed his hand to his head, and gasping once fell back dead. So sudden was the off-taking that the family of Dr. [Randolph] Marcy were not summoned, and the only persons who were present when the General breathed his last were Mrs. McClellan and her daughter, Dr. Seward and two servants of the family.[3]

As is with all famous deaths, last words were said to be muttered before McClellan expired: “I feel easy now. Thank you …” Whether this is true or not is beside the point, but it certainly adds a flare of the dramatic.[4]

George McClellan’s sudden death can be attributed to coronary heart disease, or at least that is what the American Heart Association states that angina pectoris is predominantly caused by. Whether or not he suffered from chest pains prior to October 1885 is unknown, but it is quite possible that it may have been something he previously shrugged off until it became concerning and unbearable.[5]

The General’s funeral service was held in Manhattan at the Madison Square Presbyterian Church on Monday, November 1, 1885. At the request of Mary Ellen McClellan, the funeral “would be as quiet as possible, and there would be no military honors or display whatever.” Following the service, McClellan’s remains were taken to Trenton and interred in the Riverview Cemetery.[6]

A week following the passing of “Little Mac” the Monmouth Democrat published a heartfelt obituary to the deceased general. Their words remind us that despite what is felt by some regarding his tenure with the Army of the Potomac, he was a soldier, but above all he was a man – a husband, father, and friend who was loved by many:

Verily death has claimed a costly sacrifice – but death has not won, for General McClellan was an earnest and sincere follower of the great Conqueror of Death. The secret of his life – patient, quiet, gentle, trustful, loving – was his trust in the Redeemer of men … Soldier, patriot, statesman, scholar, Christian – all these he was, and with them all, a man! We knew him and to love him … There is a void in our hearts, a vacancy in our ranks.[7]

[1] “Sudden End of a Useful and Distinguished Life,” The Orange Journal (West Orange, NJ), October 31, 1885.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Steven W. Sears, George B. McClellan: The Young Napoleon (New York: Ticknor & Fields, 1988), 400-401.

[5] American Heart Association, “Angina Pectoris (Stable Angina),” American Heart Association, http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/Conditions/HeartAttack/SymptomsDiagnosisofHeartAttack/Angina-Pectoris-Stable-Angina_UCM_437515_Article.jsp#.V3BZIWgrK00 (accessed 26 June 2016).

[6] “Sudden End to a Useful and Distinguished Life.”

[7] “Little Mac,” Monmouth Democrat (Monmouth, NJ), November 5, 1885.

This is quite interesting. Thanks for sharing.

Gimme a break?

He was a FUCKIN COWARD

Ok Beth. How many battles did you fight in?

Gimme a break?

He was a FUCKIN COWARD

George was in love with the idea of grand army. One that he built up. A beautiful thing to him. He didn’t want to see it destroyed. So he hesitated. Doesn’t make him a coward. Just mis guided as to what the army was for.