A History of Civil War Drummer Boys (Part 1)

Emerging Civil War is pleased to welcome guest author Michael Aubrecht

Throughout the history of warfare musicians have always played an important role on the battlefield. Military music has served many purposes including marching cadences, bugle calls and funeral dirges. Fifes, bagpipes and trumpets are just some of the instruments that were used to instruct friendlies and intimidate foes. But perhaps the most notable instrument was the drum. From as far back as the ancient days of Babylon, the beating of animal skins rallied the troops on the field, sent signals between the masses, and scared the enemy half to death. During the Revolutionary War, drummers in both the Continental and English ranks marched bravely into the fight with no more protection than their drums and sticks.

Drummer boys during the American Civil War were younger than their predecessors from the Revolution, but more advanced in their playing. Each drummer was required to play variations of the 26 rudiments. The rudiment that meant attack was a long roll. The rudiment for assembly was a series of flams while the rudiments for drummers call were a mixture of flams and rolls. The rudiment for simple cadence was open beating with a flam repeat. Additional requirements included the double stroke roll, paradiddles, flamadiddles, flam accents, flamacues, ruffs, single and double drags, ratamacues, and sextuplets.

Many drummers learned how to play the essential rudiments by attending the Schools of Practice at Governor’s Island, New York Harbor, and Newport Barracks, Kentucky, although the vast majority learned in the field. Some were aided by texts; the most popular by far was Bruce and Emmett’s 1862 The Drummers’ and Fifers’ Guide.

According to historian Ron Engleman:

The word rudiments first appeard in a drum book in 1812. On page 3 of A New Useful and Complete System of Drum Beating, Charles Stewart Ashworth wrote, Rudiments for Drum Beating in General. Under this heading he inscribed and named 26 patterns required of drummers by contemporary British and American armies and militias. The word Rudiment was not used again in US drum manuals until 1862.

Military drums were usually about 18” deep prior to the Civil War. Then they were shortened to 12”-14” deep and 16” in diameter in order to accommodate younger (and shorter) drummers. Ropes were joined all around the drum and were manually tightened to create tension that stiffened the drum head, making it playable. The drums were hung low from leather straps, necessitating the use of the traditional grip. Regulation drumsticks were usually made from rosewood and were 16”-17” in length. Ornamental paintings were very common for Civil War drums which often displayed pictures of Union eagles and Confederate shields.

Drums were made primarily in the important industrialized centers of the Northeast: Boston, New York and Philadelphia. There were no standards for drum construction. The shells were usually made of ash, maple or similar pliable woods. Wooden hoops were used to reinforce the drum which was “tuned” by adjusting ropes that crisscrossed around the shell and provided tension on calfskin or sheepskin heads. The four strand snare was constructed from a bronze hoop-mounted strainer with a leather anchor. Each drum featured a custom paintjob that made them ornamental. According to DRUM! magazine:

The crowning glory of many of these drums was their hand-painted decorations. Normally the drummer boy would receive his drum with the painting on the shell of the drum. Although there were no standards, a blue background was designated for an infantry unit, while a red background signified artillery. An American bald eagle most commonly emblazoned the Federal Army drums but sometimes the Confederates used it as well. Federal drums were also decorated with 13 stars for each of their 13 states. Confederate states were represented with 11 stars. With these beautiful decorations, it is no wonder that these drums were treasured long after the passionate sentiment of America’s bloodiest battle had abated.

Although most drums from that era are preserved in museums, Civil War drums still exist on the market as antiques. One can expect to pay up to $7,500+ for one in good condition. A quick look on eBay reveals the high cost for original drums. Regardless, to own an original Civil War drum is to possess a piece of history.

The younger the drummer, the more difficulty one would have lugging around these cumbersome instruments. However, that aspect didn’t deter boys from taking up the instrument. According to a brief history on Civil War drummers:

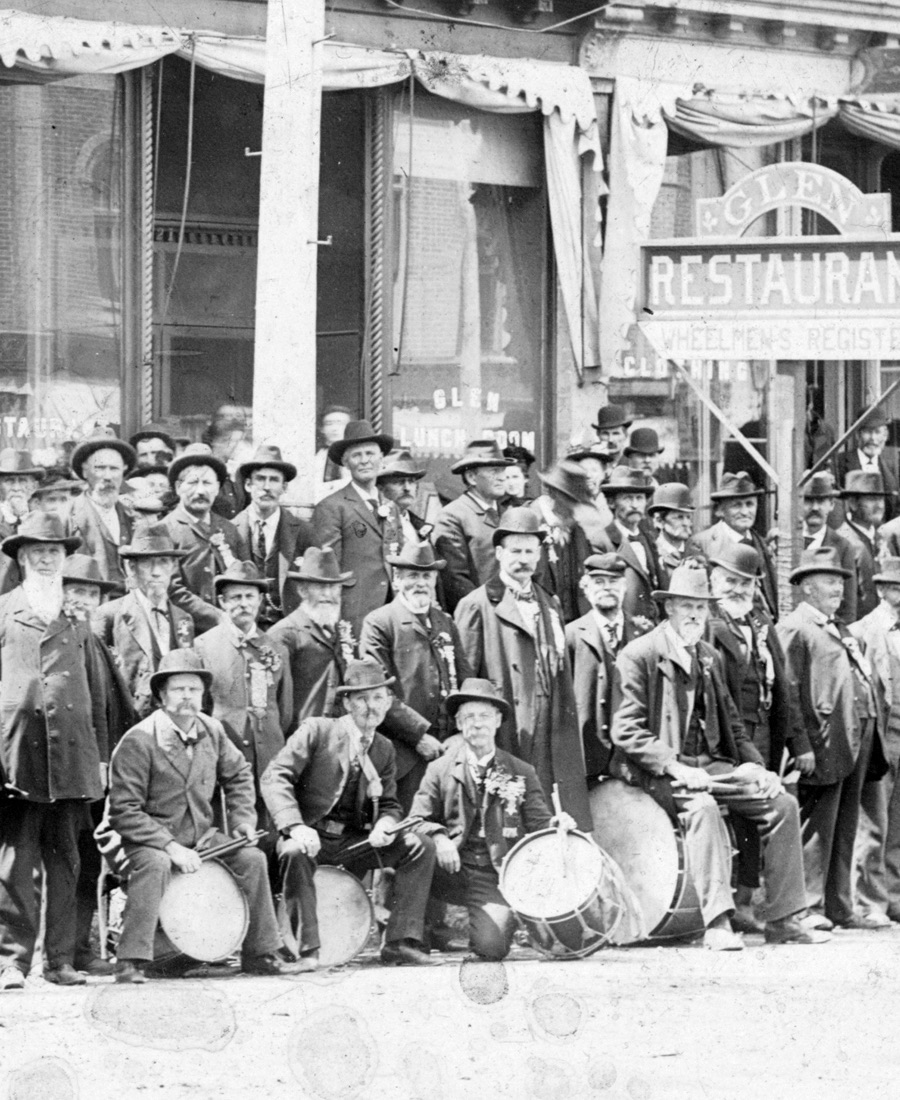

Although there were usually official age limits, these were often ignored; the youngest boys were sometimes treated as mascots by the adult soldiers. The life of a drummer boy appeared rather glamorous and as a result, boys would sometimes run away from home to enlist. Other boys may have been the sons or orphans of soldiers serving in the same unit. The image of a small child in the midst of battle was seen as deeply poignant by 19th-century artists, and idealized boy drummers were frequently depicted in paintings, sculpture and poetry. Often drummer boys were the subject of early photographic portraits.

Some believe that the youngest soldier killed during the entire American Civil War was a thirteen year-old drummer boy named Charles King. He had enlisted as a drummer boy in the 49th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry with the reluctant permission of his father. On September 17, 1862 at the Battle of Antietam he was mortally wounded in the area of the East Woods. He was carried from the battlefield to a nearby field hospital, where he died three days later.

Twelve-year-old Union drummer boy William Black is said to be the youngest person on record to be wounded in battle during the war. One of the most famous drummers was John Clem, who had unofficially joined a Union Army regiment at the age of nine as a drummer and mascot. Young “Johnny” became famous as the “The Drummer Boy of Chickamauga” where he is said to have played a long roll and shot a Confederate officer who had demanded his surrender.

Some of these young musicians marched in the ranks of the U.S. Colored Troops while contributing in their own way. Unlike their counterparts in the South, African-Americans, both free and ex-slave were looked upon as soldiers and not camp servants. Grateful for their newfound freedom many Southern slaves savored the opportunity to line up in the Union ranks and raise their muskets toward their former oppressors. Free men from the North took the opportunity to serve as their brother’s keeper. Throughout the war their drummer boys provided essential camp and field communications.

One African-American drummer boy of particularly noteworthy service was A.H. Johnson. At the age of 16, Alexander H. Johnson was the first African-American musician to enlist in the U.S. military, joining the 54th Massachusetts Volunteers under Col. Robert Gould Shaw. Johnson was adopted by William Henry Johnson, the second black lawyer in the United States and close associate of Frederick Douglass. After the war Johnson told an interviewer that he had “beat a drum every day he has been able since childhood.”

According to an article titled Alexander H. Johnson: The first drummer boy (by Meserette Kentake) Johnson quickly established himself as a reliable drummer as he and the rest of the rank and file learned the art of soldiering. He was with the unit when it left Boston for James Island, S.C., where it fought its first battle.

The skirmish, along the South Carolina coast near Charleston, occurred on July 16, 1863. Johnson noted, “We fought from 7 in the morning to 4:30 in the afternoon, and we succeeded in driving the enemy back. After the battle we got a paper saying that if Fort Wagner was charged within a week it would be taken.”

Two days later the 54th unsuccessfully stormed Confederate-held Fort Wagner on Morris Island while sustaining massive casualties. Johnson recounted, “Most of the way we were singing, Col. Shaw and I marching at the head of the regiment. It was getting dark when we crossed the bridge to Morris Island. It was about 6:30 o’clock when we got there. Col. Shaw ordered me to take a message back to the quartermaster at the wharf, who had charge of the commissary. I took the letter by the first boat, as ordered, and when I returned I found the regiment lying down, waiting for orders to charge. The order to charge was given at 7:30 o’clock.” In addition to the loss of many infantrymen, the 54th’s commanding officer fell while leading the attack.

Johnson remained in the 54th until the end of the war. In the summer of 1865 he returned to Massachusetts, bringing the drum that he carried at Fort Wagner with him. Four years later he married, settled in Worcester, Mass., and organized “Johnson’s Drum Corps.” He led the band as drum major, and styled himself “The Major.”

In 1897, a memorial to the 54th sculpted by the artist Augustus Saint-Gaudens was unveiled in Boston. The bronze relief depicts Colonel Shaw and his men leaving Boston for the South with a young drummer in the lead — a scene reminiscent of the July day in 1863 when Shaw and Johnson marched at the head of the 54th to its destiny at Fort Wagner. In 1904, Johnson visited the monument during an event hosted by the Grand Army of the Republic, the influential association of Union veterans. Many of those in attendance pointed out the resemblance of the young lead drummer and it is said that Johnson felt a great sense of pride for his participation in the war. Today the statute remains as a timeless tribute to both Johnson and the men he served.

To be continued…

* * *

Sources:

Albert A. Nofi, A Civil War Treasury: Being a Miscellany of Arms and Artillery, Facts and Figures, Legends and Lore, (Da Capo Press, 1992)

Bruce & Emmett Drummers’ and Fifer’s Guide (1862)

Carolyn Reeder, “Drummer boys played important roles in the Civil War, and some became soldiers” (Washington Post, February, 2012)

Charles Stewart Ashworth, A New Useful and Complete System of Drum Beating (January, 1812)

Chet Falzerano, “Historic Collectible: Civil War Drums” (DRUM! Magazine, December, 2011)

Elizabeth M. Collins, “The Beats of Battle: Images of Army Drummer Boys Endure” (Soldiers: The Official U.S. Army Magazine, December, 2013)

Gardiner A. Strube, The Rudimental Principles of Drum – Beating (1870)

Marcie Schwartz, “Children on the Battlefield: Heroism and Sacrifice” (civilwartrust.org)

Max Louis Rossvally, Charlie Coulson a Drummer Boy: A True Story in the American Civil War (188?)

Meserette Kentake, “Alexander H. Johnson: The first drummer boy” (Kentake Page, July 2015)

Robert H. Hendershot, “Drummer Boy of the Rappahannock” (National Tribune, Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), July 1891)

Robert J. McNamara, “Civil War Drummer Boys” (history1800s.about.com)

Ronald S. Coddington, “Colonel Shaw’s Drummer Boy” (The New York Times, March, 2013)

The Indiana Democrat, Thomas Hubler (Indiana, Pennsylvania, November, 1883)

U.S. Civil War History & Genealogy, “The Drummer Boys” (genealogyforum.com)

* * *

Michael Aubrecht is an author, as well as a drum and Civil War Historian. He has written several books including The Civil War in Spotsylvania, Historic Churches of Fredericksburg and FUNdamentals of Drumming for Kids. He also co-produced the documentary “The Angel of Marye’s Heights.” Michael lives in historic Fredericksburg. His latest project was compiling over 100 period photographs of drummer boys. Visit his blog online at https://maubrecht.wordpress.com/.

Huzzah! and welcome.

Enjoyed & shared. Are you on Twitter?

Thank you both. I am not on Twitter but I have a drum blog at: http://www.maubrecht.wordpress.com. If you search for “Civil War” it will bring up a multitude of posts on Civil War drums and drumming. You can also view my compilation of 100 period photos of drummer boys at: http://www.pinstripepress.net/CWDrummerBoys.pdf.

One of the best sites I’ve visited on the subject.

SO fascinating! Thank you!

Visited Columbus Belmont Park in Ky….awe inspiring!

Finding out all kinds of info that i didn’t learn in school, a million yrs. ago.

Fascinating….but, sad.

George B. Keady enlisted 12 Aug 1862 in the Illinois 113th Infantry Regiment Company ‘F’ at the age of 13 as a ‘musician’ . Mustered out on 20 June 1865. Any chance of finding out any more information about him from anyone? Can’t imagine a boy that young going thru the battles the 113th were in. He would be my Great Grandfather.

Pleased to find this account, as I knew little about how Civil War drummers trained or performed.

My great-grandfather Henry Clay Stoddard was a drummer with the 24th Michigan Volunteer Infantry Enlisted Aug 2, 1862, served in the 24th Reg. Michigan Volunteers, 5th Corps, Army of Potomac; saw action at Antietam, South Mountain, Brandy Station, Fredericksburg, Chancellorville, Gettysburg, The Wilderness, North Anna, South Anna, Mine Run, Siege before Petersburg and Five Forks. Was mustered out at Detroit July 29, 1865.

https://www.pinterest.com/pin/511440101414369708/?nic_v1=1aoYPJO2XnDKCcIQ%2Bxd1rmD8ZinHelVN0t%2BnzHcW7ALrbYbYcmrSJ7Hq9%2Bqldh%2BmDZ

My great great grandfather was with company K, 8th Virginia. Utterback was his name. Does anyone have a picture of his company . Thanks

There was an S.R. Bowermaster that I believe was a drummer with one of the Pennsylvania Union armies. He was captured and taken to Andersonville, where he died and is buried. I’ve been to his grave.

Is there any way to find out more about him? I’d love to find a photo or see if I’m related.

In 1954 when I was a little boy of 5 playing in the woods across from my house, I met a very old man who lived with his daughter who I learned was in her 80’s. He told me he was a drummer boy in the Civil War. The only thing I remember is that he was very sincere and proud of his service. I wish I could remember more of this chance encounter. I can only add that the location was Westfield, Massachusetts. later in life I did the math and found the veracity of his account was very possible. I cherish the memory.

Hi. Great site. I am looking for ALEXANDER MCKEAN (AM) MOORE, drummer for 33rd Iowa Infantry, Company G, 1862-1865. Any information is appreciated.

My relative,Jesse F. Clough, was “The drummer boy of Altoona.” He served with Company C, 93rd Illinois.