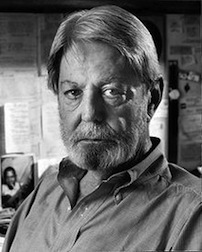

Happy 100th Birthday, Shelby Foote

Shelby Foote would have been 100 years old today.

Shelby Foote would have been 100 years old today.

Born in Greenville, Mississippi, on November 17, 1916, he died on June 28, 2005 at the age of 88 from a heart attack following a pulmonary embolism.

Foote was best known for his three-volume tome The Civil War: A Narrative, which took him twenty years to write, averaging some 500-600 words per day. “It took me five times as long to write a history of that War as it took the country to fight it,” he told writer Tony Horwitz. Of course, he quipped elsewhere, “there were a good many more them than there was of me.”

At more than 1.65 million words, the three volumes add up to 2,934 pages. The New York Times said the work “blended his practiced novelist’s touch with punctilious, but defiantly unfootnoted research.”

“I don’t think it’s a novel, but I think it’s certainly by a novelist,” Foote told The Paris Review in a 1999 interview. “My book falls between two stools—academic historians are upset because there are no footnotes and novel readers don’t want to study history.” He pointed out that the ancient Greeks “considered history a branch of literature; so do I. . . .”

Foote often argued that

the novelist and the historian are seeking the same thing: the truth—not a different truth: the same truth—only they reach it, or try to reach it, by different routes. Whether the event took place in a world now gone to dust, preserved by documents and evaluated by scholarship, or in the imagination, preserved by memory and distilled by the creative process, they both want to tell us how it was: to recreate it, by their separate methods, and make it live again in the world around them.

This has been my aim, as well, only I have combined the two. Accepting the historian’s standards without his paraphernalia, I have employed the novelist’s methods without his license. Instead of inventing characters and incidents, I searched them out—and having found them, I took them as they were.

Foote saw a close relationship between the two disciplines. “I maintain that anything you can learn by writing novels—by putting words together in a narrative form—is especially valuable to you when writing history,” he said.

Foote took tremendous flak for not footnoting his work, and the Pulitzer committee passed him over because of it, but Foote vigorously maintained that he used only sources that he found “unimpeachable.”

“[S]ources come in different categories,” he explained in a 1970 interview:

There are the memoirs by the men who were there, there are the reports and Official Records of the War of the Rebellion which were written at the time. Then there are good studies. There work of Bruce Catton has been of great help to me. Douglas Southall Freeman’s books, Stanley Horn’s books, Robert S. Henry, a lot of good treatments, and they serve as a guide through the labyrinth of the material, to keep you from missing any of it and really show you the salient features of the source material. . . . Regimental histories are not much count. They’re always interesting to read. You pick up good little features out of them. But they were written after the war, and the war took on a sheen when it was over.

Writers all had their flaws, even the best-known ones, although he often singled out Freeman as a special example. During his service in World War II, Foote carried a copy of Freeman’s Lee’s Lieutenants with him, as well as G. F. R. Henderson’s biography of Stonewall Jackson. “Freeman’s so much of a Virginian that he couldn’t see anything but Virginia,” Foote said. “He limited himself to writing about Virginia except when he sent Longstreet out for the fight at Chickamauga, and he made pretty much of a mess of that. He was so Virginia biased and his dislike of Longstreet was so strong that it warped his work. He’s not a stylist. He writes sort of jog-trot prose, but once the reader becomes accustomed to it, it somehow seems just right.”

Style, he thought, was a writer’s distinctive way of bringing something to life. “Style is not the way somebody pouts in flourishes,” he explained. “Style is the way a man is able to communicate to you the quality of his mind.”

He wished more historians took the time to learn to write better. “[S]ome of the best historians with regard to communicating facts are dreadful writers. I find them close to unreadable except in the way of research,” he told The Paris Review. “It’s as if they thought [learning how to write] an onerous waste of time. . . . I just wish more of them spent a bit more time learning how to write, learning how to develop a character, manage a plot.”

Aside from his Civil War narrative, which he finally finished in 1974, Foote wrote several novels, although he wrote only one of them—September, September—after The Civil War. “I had a dry season after I finished the Civil War narrative. I was either in a stage of exasperation or I felt there was nothing left to write,” he admitted. “Those twenty years didn’t exhaust me physically but they exhausted me from wanting to do another long work.”

Ken Burns’ documentary The Civil War turned Foote into a household name, of course. “He made the war real for us,” Burns later said. Of the film’s eleven hours, Foote appeared onscreen for nearly an hour—nearly 90 times. Biographer Stuart Chapman said Foote seemed tailored to suit audience expectations: he “played the part of being a Southern gentleman—he gave them what they wanted.”

The appearance did Foote a disservice, too, though. Captured only in soundbites, his folksiness suggests a pro-South leaning, but as Horwitz discovered when he interviewed Foote for Confederates in the Attic, Foote’s views were far more “complex” and “nuanced” than the TV clips—chosen by Burns—suggested.

My own admiration of Foote comes not because he charmed me, as he did millions of other TV-viewing Americans (although I did, indeed, find him charming). Rather, it’s because I feel a deep kinship with him. As a writer, he gets closest to what I, myself, try to do: focus on the writing of the war as much as the history. He saw the Civil War as America’s great story. “What could there be left worth writing about?” he once mused.

“Don’t underrate [the Civil War] as a thing that can claim a man’s whole waking mind for years on end,” Foote told his friend Walker Percy. “For one thing, it teaches me to love my country—especially the South, but all the rest as well.”

For more on Shelby Foote in his own words:

The Paris Review interview is available online. It originally appeared in the Summer 1999 issue.

The Tony Horwitz interview appeared in Confederates in the Attic, Chapter 7, “At the Foote of the Master.”

Carter, William C., ed. Conversations with Shelby Foote. Jackson, MS: University of Mississippi Press, 1989.

Tolson, Jay, ed. The Correspondence of Shelby Foote & Walker Percy. New York: W.W Norton & Co., 1997.

The following is the problem I’ve always had with the Paris Review interview:

“The institution of slavery is a stain on this nation’s soul that will never be cleansed. It is just as wrong as wrong can be, a huge sin, and it is on our soul. There’s a second sin that’s almost as great and that’s emancipation. They told four million five hundred thousand people, You are free, hit the road. And we’re still suffering from that. Three quarters of them couldn’t read or write, not one tenth of them had a profession except for farming, and yet they were turned loose and told, Go your way. In 1877 the last Union troops were withdrawn after a dozen years of being in the South to assure compliance with the law. Once they were withdrawn all the Jim Crow laws and everything else came down on the blacks. Their schools were inferior in every sense. They had the Freedmen’s Bureau, which did, perhaps, some good work, but it was mostly a joke, corrupt in all kinds of ways. So they had no help. Just turned loose on the world, and they were waifs. It’s a very sad thing. There should have been a huge program for schools. There should have been all kinds of employment provided for them. Not modern welfare, you can’t expect that in the middle of the nineteenth century, but there should have been some earnest effort to prepare these people for citizenship. They were not prepared, and operated under horrible disadvantages once the army was withdrawn, and some of the consequences are very much with us today.”

Very unfortunately, that fed the Burns mint-julep-drinking stereotype. Intended or not, the impression conveyed is one which diminishes his work.

I’m not sure I entirely disagree with Foote, though. I certainly wouldn’t characterize Emancipation itself as a sin, but there was no plan in place for its execution or aftermath, the well-meaning Freedmen’s Bureau was impotent, and Reconstruction was a catastrophic failure.

Ken Burns and Shelby Foote brought the Civil War into the living rooms of the American public and inspired the study of what happened in this country that tore our young nation apart.

The end of the war presented the nation with several pressing problems. One was the future of the “freedmen,” to use the 19th Century term. The war had pragmatically ended slavery, although the legal end of the institution awaited passage of the 13th Amendment, but all that had been done was to say “You are free.” Nothing had been said about “free to do what?” or “free and what?’ Foote correctly identified this problem.

It should be noted that opposition to answering those questions posed above (the 14th and 15th Amendments) did not come exclusively from the South. Both the 14th and 15th Amendments failed passage because Northern states voted against them. Both passed only when Southern states voted for them. It is, therefore, historically wrong to see Jim Crow as exclusively a Southern creation. The belief on white supremacy, called in the 19th Century ‘Anglo Saxon Superiority” was a belief widely shared throughout the U.S. and Europe.

The other problems I see present at the end of the war were:

Reestablishing working governments in the South with working relationships with the national government;

Dealing with a shattered Southern economy;

Rebuilding a sense of loyalty among ex-Confederates to the United States.

The first of these was done rather quickly and reasonably well. The third was taken care of by the passage of time. The third was not addressed and its neglect affected all those who lived in the region—ex-slave or ex-slave owner, ex-Confederate or ex-Unionist. In many important ways, the shattered economy and its long-term problems, exacerbated the matter of race relations.