The Best Missed Opportunity at Richmond

We are pleased to welcome back guest author Doug Crenshaw, who continues to look at communications mishaps during the campaigns for Richmond. Today, he turns to 1864.

As they peered over the walls of Fort Harrison, Confederate soldiers witnessed an awesome and terrible sight. Less than a mile to their front, thousands of blue-coated troops poised for an assault. To meet them, the defenders had only a couple of hundred men and four or five heavy guns. How could they hold out?

Fortifications surrounded them, but these also were thinly manned. Behind, only a ring of small forts stood between the Union army and the Confederate Capital. Things were desperate indeed!

On the night of September 28, 1864, General Ben Butler’s Army of James crossed over to the north bank of that river in an effort to surprise and capture Richmond. His X Corps went over at Deep Bottom and, on the morning of the 29th, a division of United States Colored Troops successfully attacked and drove the defenders from New Market Heights.

Meanwhile, the XVIII Corps crossed at Aiken’s landing, west of Deep Bottom. They were to march up Varina Road, attack the Fort Harrison area, then move a few miles north to meet the X Corps. The two corps would then unite and move on Richmond. While the Confederates had constructed a massive set of earthworks to defend their capital, the works were thinly manned and would be hard pressed to stop Butler’s 20,000 men.

The commanding general of the XVIII Corps, Edward O. C. Ord, decided that it would be prudent not to issue written orders for fear that Confederate spies might get their hands on them and thus ruin Butler’s nasty surprise. He verbally told George Stannard, who headed the 1st Division, to march up the Varina Road, and then turn left and drive directly towards the front of Fort Harrison. Ord stated in his report of June 15,1865, that he then ordered Charles Heckman, commander of the 2nd Division, to attack “the east front as rapidly as possible.”

This is where thing began to quickly unravel.

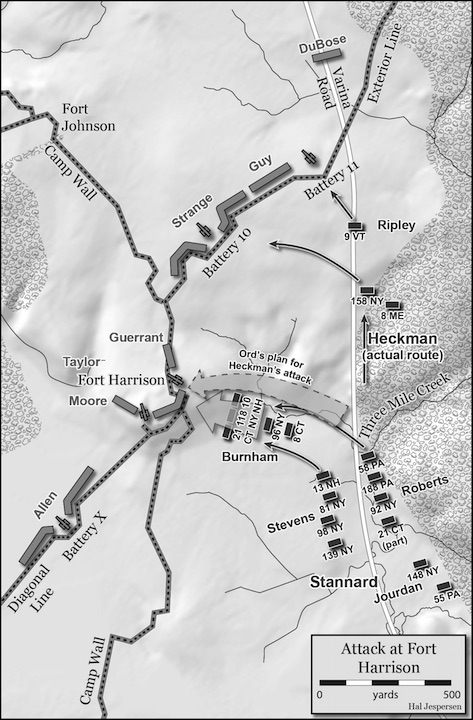

Look at the map below and view Ord’s interpretation of his instructions to Heckman versus the understanding of the 2nd Division commander.

Notice the wall of fortifications that run through Fort Harrison and up through Fort Johnson. These continued through Forts Gregg and Gilmer, just to the north. Had Heckman and Stannard both attacked Fort Harrison in unison, they would have pierced the veil of Confederate entrenchments. All of the forts in the area were open-backed, so once the Federals pierced the line, they could turn and take them by assaulting their unprotected rear. Richmond would basically be open to attack.

Unfortunately for the Union, this effort would fail. Heckman’s actual assault was slightly farther to the north. He took batteries 10 and 11, but was still outside the Confederate “camp wall,” and there he would remain. Many have held Heckman culpable for the failure of the day, and he certainly deserves a share of the blame, but a glance at the map shows that he did indeed attack the east front. It was due to the lack of clear and precise orders that Federals lost their golden opportunity.

Unfortunately for the Federals, there would be more communications and leadership problems that day.

During Stannard’s attack, all three brigade commanders went down: one killed, one wounded and one seriously ill. Added to that was the loss of several regimental leaders. Ord’s 1st Division took Fort Harrison, but they were in confusion, with Ord and Stannard being the only leadership constants. At that moment, Ord decided to head to the James River with Stannard to destroy a pontoon bridge that Robert E. Lee could have used to send Confederates reinforcements over the river. That left the remaining troops in the fort basically without direction. With no written orders, what were they to do?

Ord was wounded on the way to the river, and he sent for Heckman, his next in command. In his report, written nine months after the battle, Ord stated that he told Heckman to occupy the fort and “push on, attacking the works toward Richmond in succession.” What did that mean? Should Heckman drive to the west and attack the small forts around Richmond, or move north against forts Gregg and Gilmer? The latter would have lead him to contact the X Corps, where, according to Butler’s plan, they could then move on Richmond.

Without written orders, though, Heckman may have had no idea what the overall plan was. Instead, he squandered the morning in fruitless, piecemeal attacks. As a result, the VIII Corps basically stalled out, and perhaps the Union’s greatest opportunity to take Richmond passed them by as Lee sent massive reinforcements across the river.

There would be yet one more failure. David Birney’s X Corps was moving up the New Market Road to meet Ord, as planned, but there was no sign of XVIII Corps troops. Instead, Birney was greeted by shells from the two heavy guns of Fort Gilmer a mile away. Birney ordered Robert Foster’s small division to assault the fort, and also William Birney (the commander’s brother) to attack with his partial brigade. They were to “commence the movement in ten minutes from the receipt of order.” No time was allowed to coordinate the attack, and apparently David Birney did not try to contact the XVIII Corps to his south.

As a result, Birney’s attack failed, as Foster’s division and William’s brigade did not attack in unison, and both were repulsed in turn. Soon Lee would have 20,000 men on hand, most hardened veterans from the Army of Northern Virginia. The Union opportunity had vanished as quickly as it had appeared.

The morning of September 29, 1864 was probably the Federals’ best chance to take Richmond. After a quick victory at Fort Harrison, the Union army spent the remainder of the day in fruitless, disorganized actions. Strong leadership and clear orders could have prevented this and, instead, made the most of this opportunity. The loss of Richmond and its industrial facilities likely would have led to the end of the war in Virginia. Ord bears much of the responsibility for unwritten and vague instructions. David Birney owns a share of the blame, as well.

However, the greatest failure was that of Ben Butler. Having planned a campaign that could have worked, he was not at the Fort Harrison front when leadership was required. Butler could delegate authority, but not responsibility. As a result, many more soldiers would die or be wounded, and many more civilians would suffer. Due to Butler’s failure of September 29, the war in Virginia would continue on until the following April.

————

Doug Crenshaw is a long-time interpretive volunteer for the Richmond National Battlefield Park. His book, Fort Harrison and the Battle of Chaffin’s Farm, is available from History Press, with a new book on Glendale out this week. His is at work on a book on the Seven Days coming out as part of the Emerging Civil War Series, and is currently working on a “prequel” for the ECWS about the Peninsula Campaign.

I agree that this was the best chance to take Richmond, and your closing assessment sums up Butler’s strengths and weaknesses very well. His overall plan for this operation was outstanding, but he was not a battlefield commander, and was not present to exert authority when things began to unravel. (Perhaps he knew his own limitations, in which case he should have given stronger authority to Ord or Birney to command the entire operation.) Richard Sommers’ book on this offensive—“Richmond Redeemed”—is one of the best operational studies I’ve read.

On Dr. Sommers: Not only is his book fantastic, but he is one of the most kind gentlemen I have met. I hope you have the opportunity to meet him. Also, his dissertation was the basis for his book and it is larger, with more copious footnotes.

I have a PDF of the dissertation on my laptop, but I confess I have not looked at it a lot.

We published a revised edition a couple years ago of “Richmond Redeemed.” Oh the irony since I read his first edition in 1981 on a rock and roll tour bus (left bunk, bottom). Boy did I get teased. And who knew?

I even got him to sign it in 1989.

When he and his wife Tracy stayed with us last year, I told him that story on my back deck, showed him the book, and then had him resign it. He is a marvelous guy, his wife is wonderful as well, and it was a pleasure to publish him. Plus they love dogs. What more is there?

(We are work on another, much smaller, Sommers’ title; more on that to come.)