“Unparalleled Insult and Wrong to the State”: Unionism and the Camp Jackson Affair of May 1861 (Part 1)

Society of Missouri.

Emerging Civil War is pleased to welcome guest author Kristen M. Trout

On May 13, 1861, the headline “Fight Between Rioters and the Home Guard – Several Persons Killed” adorned the covers of the nation’s most popular newspapers.[1] St. Louis citizens recalled, “[T]he large, usually lively city had a troubled, depressed appearance. The streets and public places were empty of people.”[2] Just three days prior, the brewing tensions between Unionists and Secessionists in the slave state of Missouri came to a climactic roar. Twenty-eight bodies were scattered across the planked Olive Street. Seventy-five civilians were injured.

No two accounts matched in the confusion of gunshots, stone throwing, and screaming. For Unionists, a civilian radical fired the first shot and taunted the Dutch troops. For Secessionists, the German troops fired the first shots into a crowd of innocent civilians, a result of government overreach. However, for those who considered themselves “conditional Unionists” their views on the matter varied before the massacre, but they all had a strong opinion after. One of these was a rather popular, famous Mexican War hero and politician by the name of Sterling Price, who would quickly abandon Unionism for a new cause of protecting Missouri and fighting for its secession.[3]

The roots of the Camp Jackson Affair can be traced back decades prior to when Missouri was officially admitted to the Union in 1821 without restrictions on slavery. The fertile inexpensive ground, abundance of rivers, open fields and woodlands, and the ability to bring slaves legally to the new state attracted many yeoman farmers and slave owners from the South. Families from Virginia, Kentucky, and Tennessee poured into Missouri hoping to take advantage of the potential prosperity. The Price family from Prince Edward County, Virginia established a home along the Missouri River. By the 1840s, though, a new group of migrants would change the demographics of the state.

Following the failed European Revolutions of 1848, thousands of German immigrants poured into the state for, “the great fertility of the soil, its immense area, the mild climate, the splendid river connections, the completely unhindered communication in an area of several thousand miles, the perfect safety of person and property, together with very low taxes,” reported a German traveler.[4] Many Germans resided in St. Louis, where kleindeutschlands (small Germanys) grew and prospered. Even more importantly, these Germans were primarily pro-Republican and anti-slavery, compared to the more Democratic, pro-slavery Southerners that resided throughout the rest of the state. These distinct groups would clash head-to-head at Camp Jackson.

National Battlefield.

In the years leading up to the Civil War, most Missourians opposed the idea of secession, even after the election of Abraham Lincoln. Missouri voted for Northern Democratic candidate Stephen A. Douglas, with John Bell coming in a close second. Missourians primarily backed Democrat Claiborne Jackson for governor, who openly supported Douglas, but was a secessionist in disguise. Governor Jackson hoped Missouri would follow the paths of the seven seceding states.

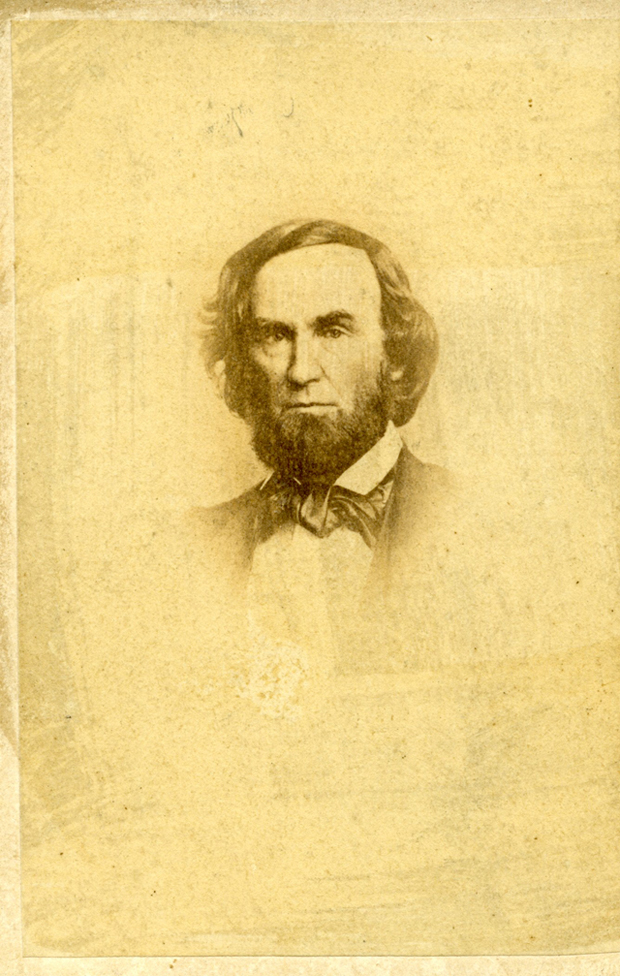

In February 1861, the Governor convened a constitutional convention to decide whether Missouri should secede. Former Governor Sterling Price was elected chairman of the convention. Price’s views, according to Lieutenant Governor Thomas C. Reynolds, “were decidedly Unionist; the only exception being his voting with the minority toward the close of the first session of the convention, for a resolution to the effect that if the Union could not be preserved, Missouri should join the Confederacy.”[5] In the eyes of Daniel M. Grissom, a Unionist, Price had an “emphatic and avowed Unionism that indicated him for president of the State Convention of 1861.”[6] Governor Jackson believed the convention would side with seceding states, but it did just the opposite. By a vote of 98 to 1, the delegates slated their state to remain with the Union. Price, co-chairman of the Committee on Federal Relations in the Missouri state convention, affirmed that there was “no adequate cause to impel Missouri to dissolve her connection with the federal Union.”[7]

Courtesy of Wilson’s Creek National Battlefield.

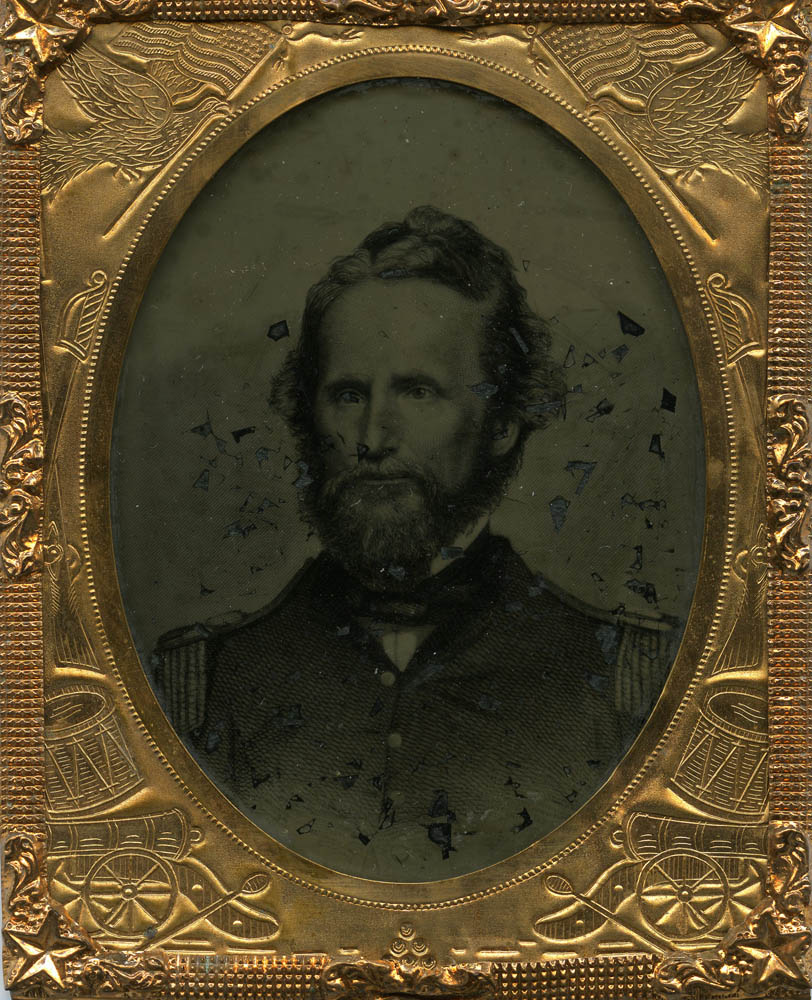

Even though it seemed as if Missourians were nearly unanimous in voting down secession, the issue continued to fester, specifically amongst the diverse population of St. Louis. In the wake of the 1860 election, secessionists Basil Duke, Colton Greene, and Rock Champion formed the Minutemen, a paramilitary force to, “fight with and for the South.”[8] At the same time, Francis P. Blair Jr., the son of Blair Sr. and brother of Montgomery, along with Army officer and ardent Unionist Capt. Nathaniel Lyon mobilized units of the St. Louis Wide Awakes, mainly made up of Germans, to counter the growing secessionists with the Home Guards. In March 1861, Lyon wrote a friend about the tense atmosphere as Missouri’s fate remained uncertain, “[T]he secessionists have laid their plans for an extraordinary effort, to be stimulated upon the indignation at Lincoln’s inaugural address – at that time a secession flag was raised in the City, and riot threatened.”[9] The violence he predicted would soon erupt.

* * * *

Kristen M. Trout is the Programming Coordinator and Historian at the Missouri Civil War Museum in St. Louis, Missouri. She graduated from Gettysburg College in 2014 with a BA in History and Civil War Era Studies, and is currently pursuing her MA in Nonprofit Leadership and Management at Webster University. A native of Kansas City, Kristen has a fond interest in the Civil War in Missouri, Civil War medicine, and the war experiences of soldiers.

[1] “Highly Important from Missouri,” New York Herald (New York, New York) May 13, 1861.

[2] Memoirs of a Nobody: The Missouri Years of an Austrian Radical, 1849-1866, translated by Steven Rowan (St. Louis: Missouri Historical Society Press, 1997), 338.

[3] The papers of Sterling Price were destroyed in a fire in 1885.

[4] Gottfried Düden, Report on a Journey to the Western States of North America [Bericht über eine Reise nach den westlichen Staaten Nordamerika] in, William Parrish, A History of Missouri: 1820-1860 (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2000), 38-39.

[5] Thomas C. Reynolds, General Sterling Price and the Confederacy, Robert G. Schultz, ed. (St. Louis: University of Missouri Press, 2009), 24.

[6] Daniel M. Grissom, “Personal Recollections of Distinguished Missourians: Sterling Price,” Missouri Historical Review 20 (1925): 111.

[7] Committee on Federal Relations, in James Denny and John Bradbury, The Civil War’s First Blood: Missouri, 1861 (Boonville: MissouriLife, 2007), 16.

[8] Snead, The Fight for Missouri: From the Election of Lincoln to the Death of Lyon (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1886), 107; Thomas Snead was Governor Claiborne Jackson’s aide and would later become adjutant to General Sterling Price. His views shown in The Fight for Missouri are naturally biased towards the Confederacy and to the secession movement.

[9] Letter from Nathaniel Lyon to Dr Scott, March 7, 1861, in Grace Lee Nute, “A Nathaniel Lyon Letter,” The Mississippi Valley Historical Review 9 (1922): 143.

Always interested to hear each State’s process on deciding whether or not to leave the Union. Nice article and I look forward to more.

Thanks for reading the post, Richard! Make sure you read the second half of the article. Stay tuned for more on Missouri and the Trans-Mississippi West!