Mexican-American War 170th: Battle of Buena Vista

February 23, 1847: 170 years ago today, the mountain passes and gorges near the hacienda of Buena Vista filled with the ripping crackles of musketry and booming concussion of artillery. The day saw a numerically superior Mexican force throwing itself at American lines; the outcome of the battle could throw American operations in Mexico into utter disarray.

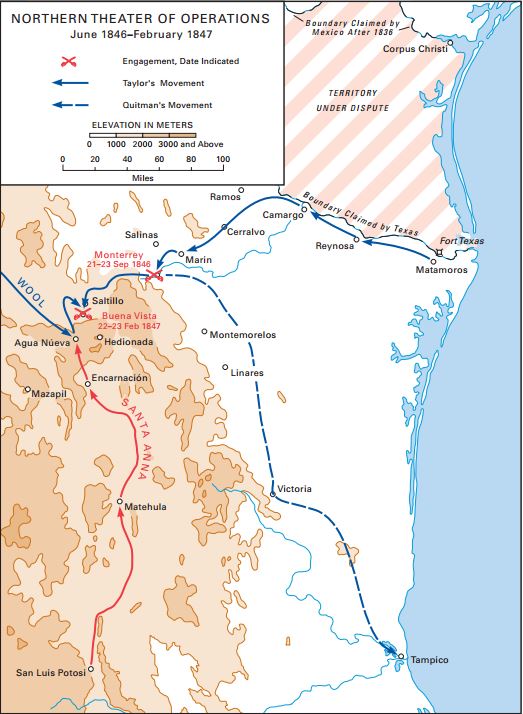

Following the capture of Monterrey, Mexico in September 1846, American and Mexican forces settled into an uneasy armistice. Pressured by President James Polk, who worried about the free time an eight-week armistice would give Mexico, Maj. Gen. Zachary Taylor alerted his counter-parts that the cease fire would end on November 13. Both sides eyed each other warily from the mountain passes in northern Mexico and settled into a tense winter.

Throughout the winter of 1846-47 there were small skirmishes and forced marches back and forth. Guerilla fighters stabbed out at American patrols, and Yankee dragoons chased their elusive enemies. Taylor moved the bulk of his troops towards Saltillo, a town about 55 miles south of Monterrey, trying to stab further into central Mexico. While his cavalry troopers skirmished, Taylor tried to keep his volunteers in order.

The volunteers, who had flocked to arms when the war began the previous summer, thirsted for action and grew bored of occupation duty. With little else to do, the inexperienced volunteers “often slipped away from camp to drink and gamble.” Local populations soon “charged volunteers with theft, assault, rape, and other violent crimes.”[1]

Taylor had to keep his volunteers away from trouble because the regulars he had used to such good order the previous summer and fall were steadily being shipped away from him. President Polk had agreed to strip away the regulars and give them to Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott, who continued to plan his own offensive against Mexico. In a letter he wrote in late January, 1847, Taylor complained, “We now begin to see the fruits of the arrangements made at Washington. . . to take from me nearly the whole of the regular forces under my command.”[2] By February, the only regulars Taylor had left were some dragoons and three batteries of artillery—the rest of his force available to him were volunteers of mixed quality and combat experience.

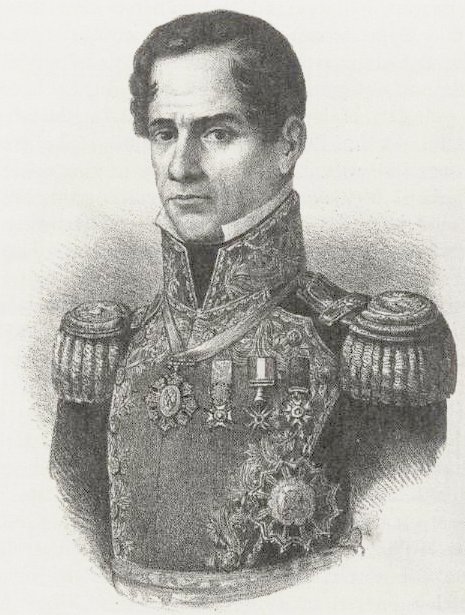

As Taylor’s forces were slowly dwindled by paper-pushers in Washington, trouble was coming to him from the south. On January 13, Mexican soldiers killed an American courier and then found orders detailing units away from Taylor on the corpse. Santa Anna knew of Taylor’s diminished force, and knew now was the time to strike.[3] Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, commanding some 15,000 troops pushed his men through a grueling 280-mile march north, approaching Taylor. If Santa Anna could get to Taylor, and defeat him, the shattered American forces would have to retreat back to Monterrey, and maybe even have to give up the key city they had just captured the previous fall.

Santa Anna’s men drove north, so that by late February they closed on Taylor’s command. Compared to Santa Anna’s 15,000 men, Taylor could look to about 4,700 men, with only the smattering of regular units already mentioned.[4]

By February 21, forward elements of both forces were trading shots, and Santa Anna’s legions steadily closed in. February 22 saw more skirmishing, but darkness brought an end to the fighting before it could fully explode. Taylor had drawn his forces close around Buena Vista to deployed them for the morning.

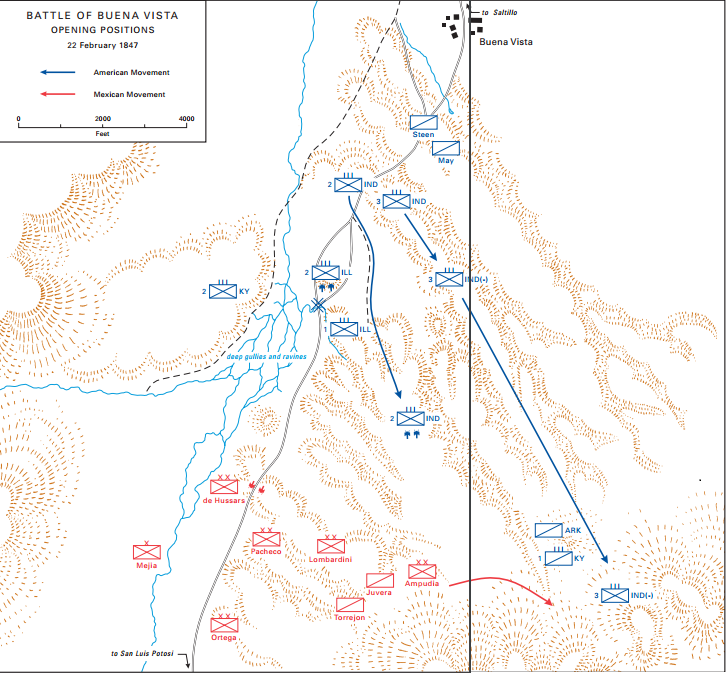

While Taylor faced daunting odds, he had the landscape to his favor. Buena Vista sat squarely on the road to Saltillo, and the road wound itself through passes of the Sierra Madre Mountains. The high rock faces created defilades, where Mexican units would be funneled into killing zones of American muskets and cannon. Taylor and his subordinates placed his infantry amongst the road and passes and carefully positioned other units atop a plateau that gave the Mexicans the best chance to wrap around the American left flank. Beefing his line, Taylor scattered guns from the various batteries of regular artillerymen amongst his infantry. Not all of Taylor’s infantry were on hand yet, some still marching south from Saltillo. Leaving the battlefield to his subordinate, Brig. Gen. John Wool, Taylor left to bring up the remainder of his forces.[5]

A miserable night of cold rain gave way to a bright February 23. Santa Anna wasted no time in unleashing his regiments. By around 8 AM Mexican units pushed towards the American position. Rather than hitting the entire length of the American line at once, Santa Anna planned his attacks as echelons—successive waves hit the American line like battering rams, hoping to find a weak point.

On the American right, located directly on the Saltillo Road, the gorges and rocky faces played exactly how Taylor and John Wool had planned. “Gullies to their left and steep slopes to the right prevented the Mexicans from maneuvering off the road or into linear battle formation.” As the Mexicans got into range, first American cannon hammered the columns, flaying them into bloody strips. Getting closer, the Mexicans were pounded by sharp volleys of musketry fire. Unable to bear the fire, the Mexicans shrunk away.[6]

On the American left, however, Mexicans curled around the positions and climbed atop the plateau. Now it was the Mexicans’ turn to fire devastating volleys into the American ranks. Crumbling into fragments, Illinoisans, Indianans, and Kentuckians steadily gave ground, surrendering the plateau to their Mexican counterparts.

The battle was about two hours old when the American left gave way, and it was then Zachary Taylor arrived on the field at the head of his last remaining reserves, the Mississippi Rifles under Colonel Jefferson Davis. Taylor described the situation as he arrived on the field: “The enemy was now pouring masses of infantry and cavalry along the base of the mountain on our left, and was gaining our rear in great force.”[7]

Taylor acted quickly, and changed the tide of the battle. He ordered Davis’ Mississippians to surge forward and turned to Captain Braxton Bragg, ordering Bragg to bring his battery of artillery to the immediate point of danger. The future commander of the Army of Tennessee rushed his guns in, including one commanded by Lieutenant George Henry Thomas, the future “Rock of Chickamauga.” An apocryphal story has Taylor calling out, “A little more grape [canister], Captain Bragg.” Taylor more likely yelled out, “Double shot your guns and give ‘em hell, Bragg!”[8]

Jefferson Davis’ counter-attack hit the stunned Mexicans. Davis wrote, “The progress of the enemy was checked. We crossed the difficult chasm before us under a galling fire, and in good order renewed the attack upon the other side. The contest was severe—the destruction great upon both sides.”[9] Still mounted on horseback, Davis presented a stark target and a musket ball slammed painfully into his right ankle. The one-day president of the Confederacy stayed on the battlefield, making sure his unit didn’t falter.[10]

The sudden American counter-attack surprised the Mexicans who felt victory so close at hand. A final attack of Mexican cavalry was checked, and Santa Anna’s men sulked back to their starting points. Scanning the battlefield, Taylor wondered if the Mexicans would come again on the morning of the February 24, but a new day found the Mexicans retreating back into the heart of Mexico. Having come so perilously close to breaking Taylor’s back, the Mexicans found themselves dealt another defeat. Santa Anna’s men “had lost belief in itself,” historian Jack Bauer wrote.[11]

Buena Vista left almost 670 Americans killed, wounded, or missing, some “about 14 percent of the 4,594 men engaged.”[12] Included amongst the dead lay Henry Clay Jr., the son of the prominent statesman who had so ardently opposed the Mexican War in the first place. As historian Amy Greensberg notes, Clay’s “son’s death shook him deeply and forced him to reexamine his life. . . he turned to religion for solace.” A war that thousands went to arms for was coming home with lists of casualties, just like another war would do in 14 years time.[13]

Santa Anna never recovered from his defeat at Buena Vista. While Taylor had lost 670 men, Santa Anna suffered close to 3,500 losses.[14] “The Buena Vista campaign represented Santa Anna’s sole offensive of the whole war,” Jack Bauer writes. He retreated further into Mexico to lick his wounds and regroup.

Though he had won, Zachary Taylor’s own force was too beat-up to do much more. He took his own bloodied units and “consolidated all his forces at Monterrey.”[15]

Thus the war in northern Mexico, at least on a grand strategic scale, came to an end. Now the war’s pendulum would swing towards central Mexico, and both sides readied themselves for more fighting in the months to come.

______________________________________________________________

[1] Stephen A. Carney, Desperate Stand: The Battle of Buena Vista (US Army Publications, 2008), 9. http://www.history.army.mil/html/books/buena_vista/CMH_73-4.pdf

[2] Zachary Taylor, Letters of Zachary Taylor: From the Battle-fields of the Mexican War (Rochester: N.p, 1908), 84.

[3] K. Jack Bauer, The Mexican War: 1846-1848 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1974), 206.

[4]Carney, 16.

[5] John S.D. Eisenhower, So Far From God: The U.S. War With Mexico, 1846-1848 (New York: Random House, Inc., 1989), 185; Zachary Taylor’s Report on the Battle of Buena Vista.

[6] Carney, 24.

[8] Francis F. Kinney, Education in Violence: The Life of George H. Thomas and the History of the Army of the Cumberland (Chicago: Americana House, 1991 reprint), 44.

[9] Jefferson Davis Report on the Battle of Buena Vista, quoted in Jefferson Davis: Ex-President of the Confederate States of America: Volume I, ed. Varina Davis (New York: Belford Company, 1890), 321.

[10] Jefferson Davis, The Papers of Jefferson Davis: Vol. 3, ed. James T. McIntosh (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1981), 122-123.

[11] Bauer, 217.

[12] Ibid.

[13]Amy Greenberg, A Wicked War: Polk, Clay, Lincoln, and the 1846 U.S. Invasion of Mexico (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2012), 167.

[14] Bauer, 217.

[15] Carney, 36.

When I used to drive from Long Beach, CA to Fort Tejon for reenactments, I always loved to pass a series of freeway off-ramps: Lincoln, Scott and Buena Vista–all in a row. I always wondered if this was on purpose, or if anyone else even noticed.

An interesting thought for sure.

Fascinating reading !

Thanks David!

In Mexico this battle is considered a draw or a Mexican victory. Would you entertain it as a draw? I think it was a marginal US victory myself.