Union Balloon Corps: Part 1

It has been said that the art of spying is as old as war itself. The commanders of yesterday understood, as do our military leaders understand today, that reading and predicting enemy movements is an integral part of battle strategy. An army needs more than supplies and soldiers to claim victory. Although methods of information gathering, battlefield maneuvers, and weaponry have evolved over time, the need for secret intelligence has remained.

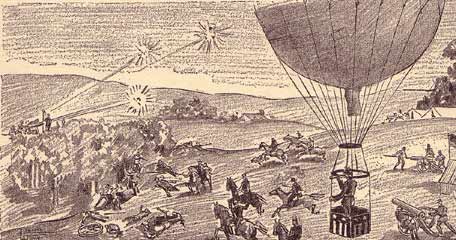

Espionage was key in the American Civil War. Military leaders employed scouts upon whom they depended for valuable information. Scouts came in many shapes and sizes, ranging from entire mounted patrols to a single individual capable of slipping behind enemy lines. Most scouts worked hard to remain hidden, but some spying was conducted out in the open. The Union Balloon Corps was a small group of men who transformed aerostats (air ships or hot-air balloons) into air-war mechanisms for reconnaissance purposes.

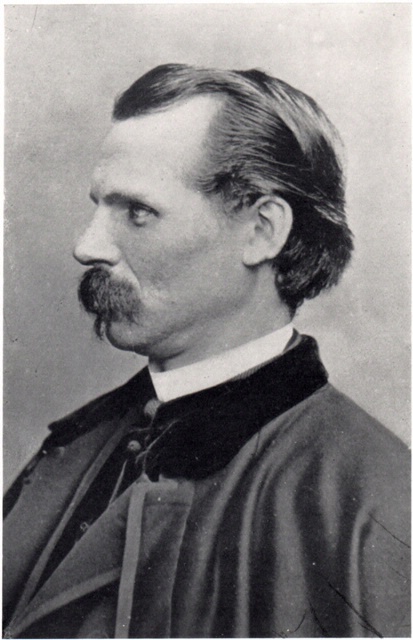

The most famous Civil War aeronaut was Thaddeus S. C. Lowe, who had always dreamed of crossing the Atlantic by air. Lowe spent many years preparing for his journey, campaigning for his cause and developing a specialized balloon. Under the advice of Smithsonian Institute Professor Joseph Henry, Lowe decided to do a trial run over land before attempting the 3,000 mile journey across the Atlantic. Lowe inflated his great helium balloon – christened “The Enterprise” – in April 1860 in a vacant lot in Cincinnati, Ohio. A crowd of spectators watched him float into the air. In just nine hours, Lowe and his balloon made a successful landing on the coast of South Carolina.

Unfortunately for Lowe, his victory was cut short when he realized that South Carolina had

seceded from the Union just four short months ago (being the first state to do so). Without today’s quick methods of communication, the folks in South Carolina had not heard about Lowe’s test flight. They had no idea what to think of the flying balloon and its occupant, who dropped out of the sky with a Yankee newspaper. Many people demanded Lowe be shot on sight – but the resourceful airship captain talked his way out of the situation and immediately boarded a train to the state’s capital, Columbia.

An angry crowd was waiting for him when he stepped off the train. Many were calling him a spy, and again came the call to shoot him on the spot. Lowe was arrested and thrown in prison until a local professor – who knew about Lowe’s aeronaut studies – convinced the authorities that the test flight was not a spying mission. Later, as Lowe made his way back home, he realized that his dream of crossing the Atlantic was far less important than the necessity of serving his country. And that’s when the idea struck him that his balloon could be of use to the Union Army.

Over time, what the southerners originally feared about Lowe became a reality. Lowe believed that – with his balloons – the Union would be able to successfully spy on its enemy from the air. They could gather intelligence on troop numbers, movements, and fortifications without entering firing range. Other scientists had presented similar plans to the Union Army, but Lowe had connections that enabled him to arrange a meeting with President Lincoln just a few days after he arrived in Washington, D.C.

The president was highly interested in Lowe’s plans, particularly the claim that he would be able to provide military direction to the commanders on the ground from his observation point in the balloon. Such a feat could be achieved, explained Lowe, by stringing a telegraph wire from the ground to the balloon’s observation basket. Lowe proved his theory by successfully sending a message in morse code from his balloon to a local telegraph station. The message was forwarded to the White House, and by August 1861 the idea of a Union Balloon Corps quickly began to take shape.

Helium ?

Hot air is incorrect. Helium is incorrect. Coal gas for few flights and later hydrogen would be correct. Year at end of Part 1 is a misprint 1861, not 1891. Number of statements are misleading. Need to read some sources, especially Haydon.