Stapleton Crutchfield: Stonewall’s Wounded Comrade

The ambulance lurched ever forward with a jerky, swaying motion. Pain dazed comprehension. General Jackson wounded? Lying just inches from him? How badly was the commander hurt?

Exacerbated by the movements over the rough road, the dizzying, unrelenting agony radiated from his own broken leg. He managed to get the surgeon’s attention. He didn’t ask to halt or for relief. He inquired if the general was dangerously hurt.

Dr. McGuire answered without false assurances, saying that the general was very seriously wounded. Hearing that, he groaned and gasped, “O, my God!” [i] Where, when, and how would this torturous journey end?

Colonel Stapleton Crutchfield – chief of artillery for the Second Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia – endured the ambulance ride from the battlefield to the field hospital with his wounded commander, General “Stonewall” Jackson. To some extent, the commander and subordinate’s lives had been intertwined for several years through their academics and military service.

Born on June 21, 1835, Crutchfield grew up on the family’s plantation in Spotsylvania County. He attended Virginia Military Institute (VMI) in Lexington, Virginia, eventually graduating in 1855. Scholarly and serious, Crutchfield accepted a teaching position at VMI, first serving as an assistant and later as a professor of mathematics and tactics. Thus, Crutchfield and Jackson both taught at VMI, but the former seemed to have more understanding of his subjects and better teaching methods. While living in Lexington, Crutchfield joined the Episcopalian Church and further revealed his love of academics and literary by supporting the local library and a debate club.[ii]

When the Civil War began in 1861, Crutchfield briefly served as the Institute’s temporary superintendent before accepting the rank of major in the Confederate forces. He changed regiments frequently in the next months, plagued by poor health and shuffled by unit reorganization. In the spring of 1862, General Jackson (commander of the Shenandoah Valley Military District) arranged for Crutchfield’s commission and appointment: Colonel, Chief of Artillery for General Jackson. Crutchfield arrived in his former instructor and colleague’s camp just as the 1862 Valley Campaign began.

Crutchfield served as Chief of Artillery for the next year through the triumphant moments and leadership challenges of Jackson’s command. Among his peers, Crutchfield gained a reputation for being taciturn and fond of rest, leading a few to conclude laziness was his besetting sin. Others admired his knowledge and literary opinions which enlivened dull winter evening.[iii] Though clearly accepted into the “inner circle” of Jackson’s young staff officers, accounts of Crutchfield present a reserved young man anxious to control the artillery and please his general. A fellow officer described him as “witty, droll and handsome.”[iv]

General Jackson played with artillery and worked it into his battlefield plans, sometimes directing gun placement himself. Field guns had built his reputation in the Mexican-American War, and he took interest in his artillery’s success during the Civil War. Typically, Crutchfield excelled as he performed his duties of coordinating, directing, supplying, and reporting; sometimes, he performed the “impossible” – like overseeing the placement of artillery on Harper’s Ferry Maryland Heights in the autumn of 1862 to facilitate the capture of that town. On an earlier occasion during the Seven Days Battles around Richmond, Crutchfield’s absence due to debilitating illness created an artillery debacle at Malvern Hill – illustrating his importance for implementing orders for the field guns.

During the Battle of Chancellorsville on May 2, 1863, Colonel Crutchfield rode forward to oversee the placement of batteries in the darkening woods. Likely unaware that his commanding officer had later made the decision to scout toward the Union lines, the artillery chief and his assistant busied themselves with their duties; they directed return fire as Union guns began to shoot toward the turnpike area shortly after infantry had fired at unknown riders trying to enter Confederate lines. In the artillery exchange, Crutchfield and his assistant – Major Rogers – fell with bad wounds. Crutchfield’s injury – shattered bone below the right knee – started him on a long, uncomfortable journey toward the rear, probably first by stretcher (or simply carried), then by ambulance.[v]

Meanwhile, General Jackson had been wounded by those shots from the infantry preceding the artillery exchange. The artillery impeded his removal from the skirmish lines while messengers were sent for the medical director and an ambulance. The ambulance they found for Jackson was the one already transporting Colonel Crutchfield toward the field hospital.

Joined by Dr. McGuire who examined both wounded men, the ambulance continued its way. Somewhere along the way, Jackson whispered to the surgeon, asking if Crutchfield was badly injured; McGuire told him the artillerist’s injury did not seem life-threatening, and Jackson seemed satisfied with the assurance. Moments later, Crutchfield quietly asked the doctor about Jackson’s injury, and the news that it was serious incited a groaning exclamation from the colonel. Alarmed for his comrade’s suffering cry and supposing it was caused by the rough journey, Jackson begged McGuire to halt the ambulance and ease Crutchfield’s pain.[vi]

Crutchfield disappears from most accounts once the ambulance arrived at the field hospital. Undoubtedly, Dr. McGuire and his assistants were preoccupied with the general’s stabilization and care, but someone would’ve placed Crutchfield on a cot or taken him directly to an operating table, depending on the circumstances. With no medical records or accounts to cite at this time, it’s probably best not to speculate on the specific details of the colonel’s field hospital experience. At some point, his right leg was amputated, and he would’ve awoken from an anesthetic-induced haze to find his shattered limb gone. Lying motionless, perhaps he wondered what would happen to him…and what would happen to his general.

A couple days later on May 4, Crutchfield and Jackson were again placed side by side in an ambulance to be sent away from the battle lines for recuperation. Dr. McGuire and other regularly-cited eyewitnesses didn’t record any conversation between the general and artillerist, but surely they said something to each other. Both had been shot on the same night, hauled in the same ambulance, and operated upon in the same field hospital. And both faced life missing a limb; Jackson lost his left arm – Crutchfield, his right leg.

Somewhere near Spotsylvania Court House, Crutchfield and Jackson would’ve said good-bye. The colonel’s uncle met the ambulance and took his nephew to the family home to rest and recover.[vii] Though they didn’t know it at the time, that was the crossroads and the end of Jackson and Crutchfield’s journeys together.

Jackson would arrive at Guinea Station and spend the last few days of his life in the Chandler office building, surrounded by doctors, a few officers, and his beloved wife and child. He would die on May 10, 1863.

For Crutchfield, death would delay. He would recover at his family home and accept a temporary teaching position at Virginia Military Institute while he regained strength. The faculty would urge him to accept Jackson’s vacant professorship, but in 1864, he would return to military service, defending Richmond. At the Battle of Sailor’s Creek on April 6, 1865, Colonel Stapleton Crutchfield would die instantly, shot through the head. His body would be left on the battlefield as the Confederates retreated, likely buried in an unmarked grave.[viii]

But they didn’t know that at the crossroads. The general and the artillerist only knew what had happened in their pasts. As Jackson looked at the young officer, did he remember him as a student, as a colleague, as a strategist, as a capable artilleryman on so many victorious battlefields? Did Crutchfield think of the moments of this man’s unskilled lectures in the classroom, recall their shared enthusiasm for field guns, or smile weakly at the thought of their military successes? We don’t know what they thought. If words were exchanged, they weren’t recorded.

However, one thing they both had was a memory of the wretched ride in the ambulance that night when the Confederacy faltered. Though Jackson shared his life, leadership, victories, and lessons with many officers, there was only one who experienced that wounded journey beside him as a comrade in suffering. That was the Chief of Artillery: Stapleton Crutchfield.

Sources:

[i] This scenario is entirely based on details from Dr. Hunter McGuire’s account.

Hunter McGuire, The Account of the Wounding and Death of Stonewall Jackson, Richmond Medical Journal, May 1866.

[ii] Dozier, G., & the Dictionary of Virginia Biography. Stapleton Crutchfield (1835–1865). (2013, September 23). In Encyclopedia Virginia. Retrieved from http://www.EncyclopediaVirginia.org/Crutchfield_Stapleton_1835-1865.

[iii]W.G. Bean, Stonewall’s Man: Sandie Pendleton, (1959), page 84.

[iv] Maurice F. Shaw, Stonewall Jackson’s Surgeon: Hunter Holmes McGuire – A Biography, (1993), page 20.

[v] Robert L. Dabney, The Life and Campaigns of Lieutenant General Thomas J. Stonewall Jackson, (reprint 1983), pages 692-693.

[vi] Hunter McGuire, The Account of the Wounding and Death of Stonewall Jackson, Richmond Medical Journal, May 1866.

[vii] Chris Mackowski & Kris White, The Last Days of Stonewall Jackson: The Mortal Wounding of the Confederacy’s Greatest Icon, (2013), page 37.

[viii] Dozier, G., & the Dictionary of Virginia Biography. Stapleton Crutchfield (1835–1865). (2013, September 23). In Encyclopedia Virginia. Retrieved from http://www.EncyclopediaVirginia.org/Crutchfield_Stapleton_1835-1865.

Wow, another good one ma’am. I sure do like your writing style.

A fascinating and moving story, and well told. Thanks for connecting the dots and bringing it to life.

Excellent take on a story I know well. Your descriptions are crafted beautifully. – Michael Aubrecht

Fantastic storytelling. The Second Corps missed Crutchfield’s skill at Malvern, and they would again after Chancellorsville.

Great article. Keep em coming!

just now getting around to reading this one. Well done and well written. Thanks for sharing. Alot of details on Crutchfield I had not known about until your article. Thanks again.

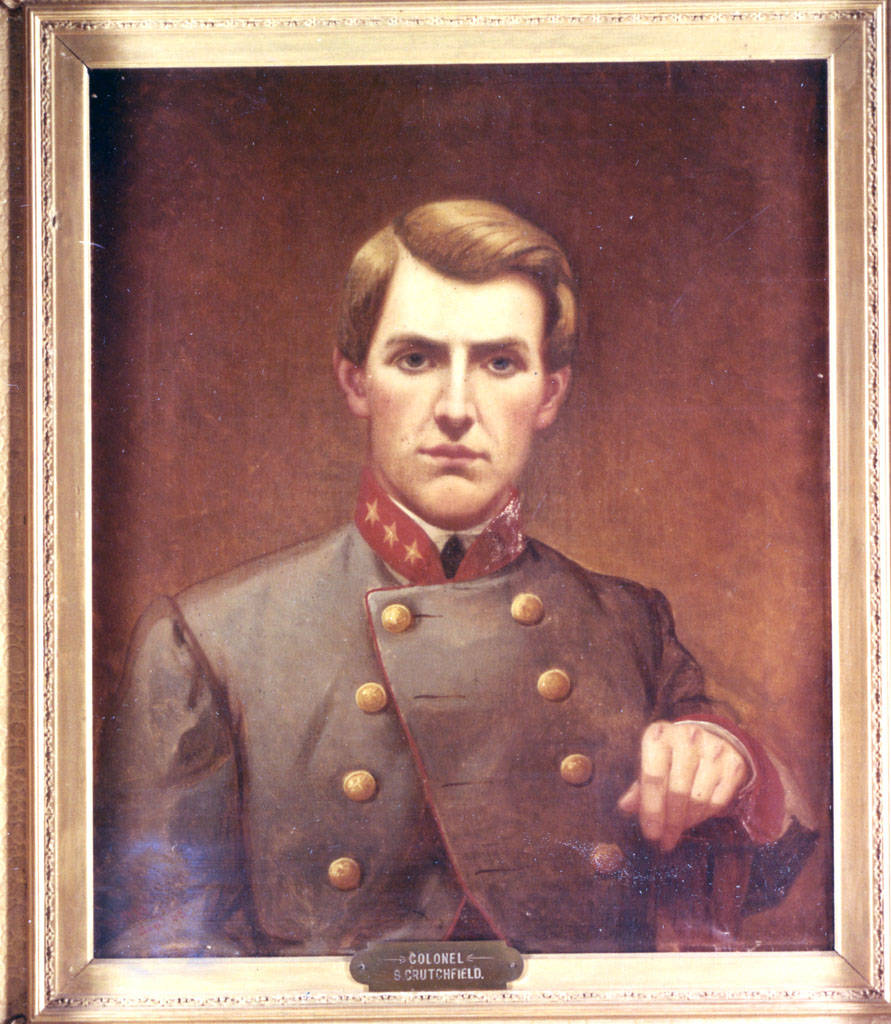

Thank you, Ms. Bierle, for amazing article about my ancestor, Stapleton Crutchfield, Col, CSA. His portrait jumped off the screen for me. Resemblance to my brother, Dr. Clifton D. Crutchfield Jr., Col, USAF Ret’d, is uncanny! Your detailed story adds much to our knowledge base.

Greatly appreciated.

Thank you for sharing; I’m glad you found the article interesting.

That original oil painting of Stapleton Crutchfield hangs in one of the lower level rooms in Preston Library at Virginia Military Institute. A couple weeks ago I was there doing some research, came around a corner and there it was! I instantly knew who it was, of course, and was excited to see the painting in person. I’m still looking for an 1850’s or Civil War era photograph of Crutchfield, but the painting is very striking and memorable.

Best,

Sarah