Stanley Matthews: Lawyer in Blue

Today, we are pleased to welcome back guest author Eric Sterner

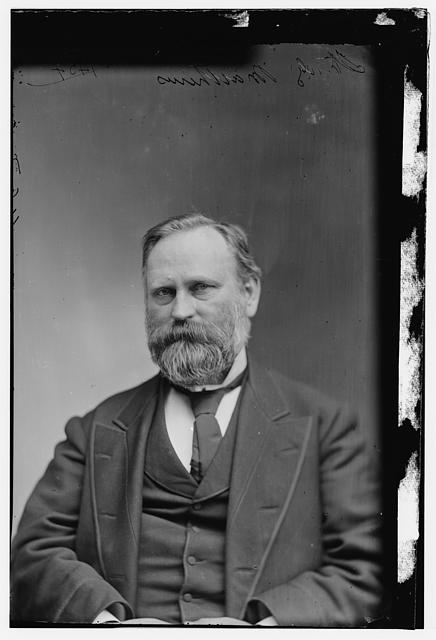

Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. may be the most famous lawyer to serve in the Civil War, but he wasn’t the only Associate Justice of the Supreme Court to wear the blue and fight for Union. Stanley Matthews of Ohio joined the court in May 1881, retired due to an 1888 illness, and died in March, 1889. In between, he married twice and fathered eight children, practiced law in Tennessee and Ohio, served as a judge, state senator, and U.S. Attorney in Ohio, was the Lieutenant Colonel of the 23rd Ohio Volunteer Infantry Regiment, Colonel of the 51st Ohio, commanded a brigade at Murfreesboro, helped make his friend and former comrade at arms, Rutherford B. Hayes, the 19th President of the United States, and served as a United States Senator from Ohio. A full life, to be sure.

Stanley Matthews was born in 1824 and graduated from Kenyon College in 1840, two years ahead of Hayes, who became a life-long friend. He studied law in Cincinnati before moving to Columbia, Tennessee to practice, eventually returning to Cincinnati an opponent of slavery. His legal career flourished in the 1850s and included stints in the Ohio Senate and as U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of Ohio. Although he had been a Democrat in Tennessee, Matthews joined the Republican Party during the secession crisis and volunteered to fight for the Union, mustering in with Hayes. By June, the two men were on their way to Columbus to join the 23rd Ohio, under West Point graduate Colonel William S. Rosecrans. Mathews was named regimental Lieutenant Colonel and Hayes the Major.

The 23rd Ohio was the first three-year regiment from the state and filled with future politicians. In addition to Hayes (the future president), Matthews (the future U.S. Senator and Supreme Court Justice), and Rosecrans, who would rise to command the Army of the Cumberland and eventually become a congressman from California, the regiment included Private William McKinley (another future president) Lieutenant Robert Kennedy (a future member of congress and Lieutenant Governor of Ohio), and Sergeant William Lyon, (another future Lieutenant Governor).

When Rosecrans was promoted to Brigadier General and sent to western Virginia, Colonel E.P. Scammon took over the regiment. It eventually followed Rosecrans to the mountains south of the Ohio River in western Virginia. Union forces were stretched thin in the Kanawha Valley, where the 23rd operated, and Lieutenant Colonel Matthews often took half the regiment on detached duty and then became de facto commander of the 23rd Ohio when Scammon was given command of a brigade. The scarcity of troops and constant marching caused Matthews to lose 25 pounds that fall according to Hayes.[i] Despite the return of occasional illness, Hayes dubbed Matthews “a most witty, social man.”[ii] In October 1861, Matthews accepted an assignment as Colonel of the 51st Ohio. Hayes noted, “It will, I fear, separate us. I shall regret that much, very much. He is a good man, of solid talent and a most excellent companion, witty, cheerful, and intelligent.”[iii] The feeling was not universal in the lower ranks. According to Russell Hastings, a Second Lieutenant in the regiment, “We honored the man but had no enthusiasm for him, and did not much regret his departure.”[iv]

The 51st Ohio operated in Tennessee, spending the spring and early summer of 1862 on provost guard duty in Nashville before marching out and joining the Army of the Ohio/Army of the Cumberland in July, only to return to Nashville. By the fall, Matthews was the de facto commander of a brigade that included the 51st Ohio. Portions of his brigade engaged Joe Wheeler’s cavalry at Dobson’s Ferry on the Stone River, during which Matthews was in the thickest of the fighting and thrown from his horse.[v] Matthews led his command at the Battle of Murfreesboro, serving again under Rosecrans, and then was stationed in Murfreesboro for the winter and spring of 1863, assigned to Van Cleve’s division in the XXI corps. Matthews was frequently ill, however, and in April 1863 resigned from the army. General Van Cleve, just returning after recovering from wounds received at Murfreesboro, assembled his forces into a square to bid the colonel farewell. One Kentuckian remembered, “Into the center rode Colonel Matthews, seated on his noted yellow horse, and accompanied by his staff…He had endeared himself to every regiment, and many of regretted his having to leave us.”[vi]

Matthews returned to Ohio, was elected a judge of the Ohio Superior Court, and eventually resumed private practice. Influential in Ohio’s Republican party, he made an unsuccessful Congressional run in 1876 then served as counsel for the Hayes presidential campaign before the Electoral Commission in 1877, which put Hayes in the White House despite his having received fewer popular and electoral votes than the Democratic candidate, Samuel Tilden. When Ohio Senator John Sherman joined the Hayes Administration as Secretary of the Treasury, Matthews took his Senate seat, but did not run for re-election. Instead, Hayes nominated him to the Supreme Court. The Senate let the nomination die with the president’s term. But, President James Garfield, another Ohioan and Civil War veteran, re-nominated Matthews at the beginning of his term. This time, the Senate quickly confirmed him. Matthews’ opinions from the bench of the U.S. Supreme Court often extended the protections of the 14th Amendment to minorities being abused by discrimination in post-Civil War America. He thus continued to defend many of the principles for which he fought, this time relying on his legal acumen instead of his sword.

[i] Rutherford B. Hayes to Lucy Webb Hayes, September 19, 1861, Rutherford B. Hayes Diary, Volume II, Campaigning in West Virginia, Rutherford B. Hayes Presidential Library and Museum, Available at http://resources.ohiohistory.org/hayes/browse/chapterxv.html, p. 96.

[iii] Rutherford B. Hayes to Lucy Webb Hayes, October 19, 1861, Rutherford B. Hayes Diary, Volume III, Winter Quarters, West Virginia, Rutherford B. Hayes Presidential Library and Museum, Available at http://resources.ohiohistory.org/hayes/browse/chapterxv.html, p. 126.

[iv] Russell Hastings, The Civil War Memoir of Russell Hastings, December 21, 1861 entry. Rutherford B. Hayes Presidential Library and Museum, Available at http://www.rbhayes.org/research/chapters-1-through-3/. Accessed July 17, 2017.

[v] Whitelaw Reid, Ohio in the War: Her Statesman, Her Generals, and Soldiers, Volume II, (New York: Moore, Wilstach & Baldwin, 1868), p. 310.

[vi] Capt. T. J. Wright, History of the Eighth Regiment Kentucky Vol. Inf. During its Three Years Campaigns Embracing Organization, Marches, and Skirmishes and Battles of the Command, with Much of the History of the Old Reliable Third Brigade, Commanded by Hon. Stanley Matthews, and Containing Many Interesting and Amusing Incidents of Army Life, (St. Joseph, MO: St. Joseph Steam Printing Company, 1880), p. 153. In his study of the 23rd Ohio, T. Harry Williams takes a less charitable view of Matthews than Captain Wright, who served under him. Williams argued that Matthews failed to connect with the men beneath him, at least in the 23rd Ohio. See, T. Harry Williams, Hayes of the 23rd: The Civil War Volunteer Officer, (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1965), p. 93-94. But, his evidence is thin and requires reading implied meaning into Hayes’ comments rather than taking them at face value and accepting the Hastings comment without question. Matthews was frequently ill and his constitution may not have been up to the rigors of campaigning.

Very interesting article. Thanks.

I second Steven’s thoughts. One very minor point – “Wendell” did not become a lawyer until after the war.

Doh! I’d definitely rephrase that sentence if I could.

Where are men and women of character hiding in this current century? Please come forward.

It would have been difficult for Hayes to become president while getting “fewer electoral votes” than Tilden. In fact he got more, as adjudged by the Electoral Commission.

You’d think so, right? The answer probably depends on how much confidence one has in the commission’s work, the accuracy of the information presented to it, and the fairness of the elections in the deep south in 1876. Tilden was up 184 to 165 in the electoral count and the conventional wisdom seems to be that those counts were legitimate. Three states–Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina, plus one elector in Oregon, were all contested with both sides claiming victory. Congress couldn’t settle the dispute itself, so it created the commission and tried to balance it politically, but even then, the state legislature in IL tried to affect the result by putting the one independent commissioner in the Senate. He promptly resigned from the commission and was replaced by a Republican, giving them a majority on the commission. The commission’s key votes after that went the Republicans’ way, awarding Hayes all 20 disputed electoral votes just days before the inauguration. So, technically, Hayes was awarded more electoral votes by inauguration day. But, I suspect there will always be an asterisk by the result.

Doesn’t mean that Hayes didn’t win those electoral votes fair and square, and I’d like to think he did, but I didn’t want to open up that can of worms in a short profile of Matthews’ Civil War service. Perhaps I should’ve rephrased that clause too!