Mexican-American War 170th: Battle of Contreras (Padierna)

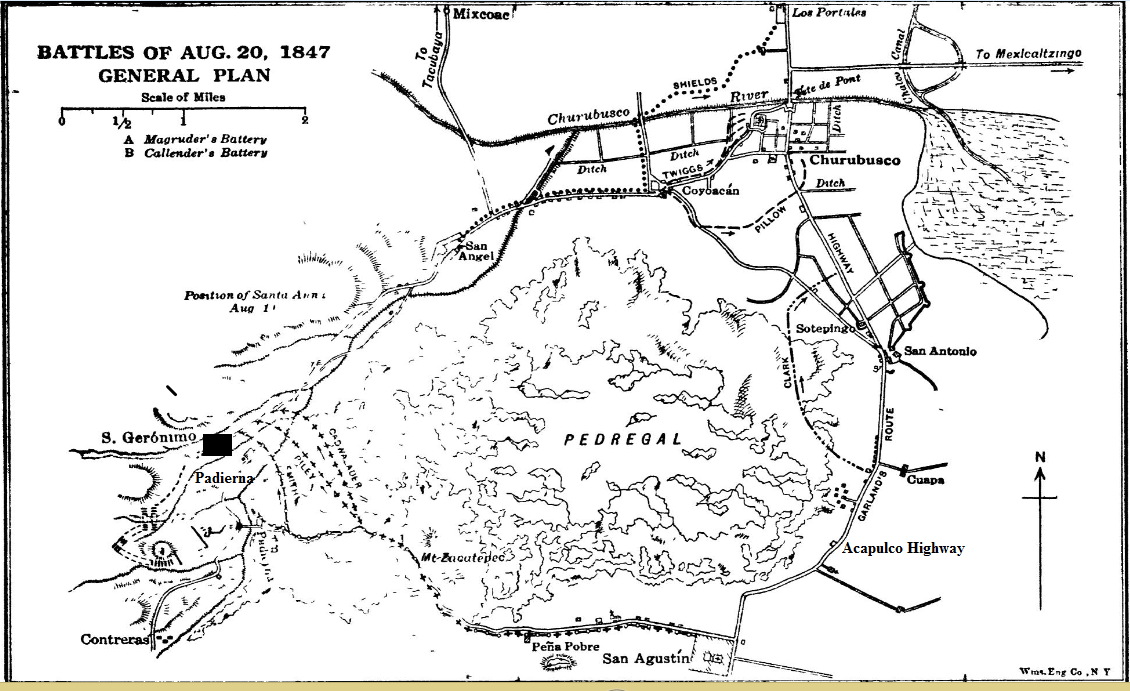

Thousands of years ago, the Xitle volcano exploded, spraying lava across the valley floor. That lava cooled to hard rocks with jagged edges in what came to be known as the Pedregal—translated to English as the Rocky Gardens. The Pedregal lay about 7-8 miles south of Mexico City and covered a wide swath of the valley. That ground, historian Justin Smith explained, “looked as if a raging sea of molten rock had instantly congealed, had then been filled by the storms of centuries with fissures, caves, jagged points and lurking pitfalls, and finally had been decorated with occasional stunted trees and clumps of bushes.”[1] To further complicate matters, the roads around the Pedregal, as Scott wrote were just a “narrow causeway, flanked on the right and left by water or boggy ground.”[2] Such ground posed a logistical nightmare for Scott’s forces who had to find a way to bring cannon and other implements for a siege forward. But the roads were essential to control as they led into Mexico City– a way forward had to be found.

Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna knew Scott faced geographical challenges, and added to it by throwing most of his available forces in front of the advancing American army. Scott’s men converged on the village of San Agustin, and north of it lay the hacienda of San Antonio along the expected main axis of advance, the Acapulco Highway. Santa Anna put soldiers and civilians to work, building fortifications in front of San Antonio. When Americans scouted the area along the highway on August 18, Mexican artillery fire pushed them back.[3]

During a council on the night of August 18, Scott decided on his plan for the following day. William Worth’s division would screen the highway to San Antonio, keeping Mexican eyes on him. Meanwhile, David Twiggs’s and Gideon Pillow’s divisions would swing to the west, towards the village of Padierna to outflank Santa Anna’s forces. The problem the flanking column faced immediately, however, was the road from San Agustin very quickly turned into little more than a mule path. Scott turned to his now familiar engineers, who he had used numerous times throughout the campaign. Robert E. Lee, P.G.T. Beauregard, George McClellan, and others, all spent time scouting the area west of San Agustin and discovered that at Padierna, a major turnpike flowed north. The trick was to just get to it.

(Justin H. Smith, “The War With Mexico” Vol. II), published in 1919

On August 19, Lee and other engineers oversaw an effort to turn the mule path into a passable road for cannon. Soldiers from Gideon Pillow’s division scraped out a road towards Padierna. During their scouting missions, the American engineers “confused the buildings at Padierna. . . with the village of Contreras which lay well to the south of the battlefield.” The ensuing fighting then, around Padierna, would forever have the incorrect name of the battle of Contreras.[4]

That fighting began on August 19 as Pillow’s and Twiggs’s divisions closed on Padierna. The Americans would be aided in the coming fight with a fracture in the Mexican high command. Commanding near Padierna was Gabriel Valencia, a man who had been an interim president of Mexico in the midst of an on-going series of coups through the 1840s. Valencia and Santa Anna could not stand each other, and hardly communicated. Santa Anna wanted Valencia to defend the turnpike north of Padierna, closer to the village of San Angel. Rather Valencia put his command into fortifications around Padierna, studded with artillery. But by going up beyond the Mexican line, Valencia “would need cooperation from Santa Anna to successful hold the San Angel Road.” But that cooperation “was impossible” due to the animosity between Valencia and Santa Anna, and Valencia even ignored his superior’s orders to fall back to San Angel. Thus a large portion of the Mexican force lay isolated—the Americans just had to find a way to exploit the salient.[5]

It would not be easy; Valencia had some 22 cannon to help defend his position around Padierna, and those guns opened fire on August 19 as the Americans closed in. Gideon Pillow, a civilian general with no prior military experience, ordered his division’s two batteries forward to contest the Mexican fire. It was an unequal challenge from the start. But the duel made men famous.

One of Pillow’s batteries belonged to the 1st U.S. Artillery under the command of John Magruder. Magruder’s guns opened fire and were soon smothered by Mexican artillery. But one of Magruder’s section commanders, Lieutenant Thomas J. Jackson stood to his pieces. An onlooker wrote of Jackson: “From the character of his position he could do little or nothing in reply, yet he stayed there without a thought of withdrawing. He had been ordered there, and his conception of duty as a lieutenant required him to stay.” Magruder kept getting pummeled, and his other section leader went down mortally wounded. Engineer George McClellan stepped in to command the two guns and continued the duel, even as a piece of shrapnel slammed into his sword hilt, bruising the young officer.[6]

To try and help his gunners, Pillow began to deploy his infantry. His first brigade, commanded by Brig. Gen. Franklin Pierce, had only recently arrived and advanced to baptism of fire. Pierce advanced on horseback, but the rocky causeway soon sent his animal tumbling. The horse crashed to the ground, slamming Pierce’s body and leaving the future president “stunned, and almost insensible.” The infantry sputtered to a halt with their commander out of the fight.[7]

The sloppy fighting by Pillow, both with artillery and infantry, incensed Winfield Scott, who arrived on the battlefield in the afternoon. Pillow had gone against orders and brought a battle on, rather than just build his road and wait for further orders. But what was done was done, and Pillow had the backing of President Polk, thus limiting how much Scott could censure his subordinate. So Scott turned to his next step.[8]

One positive of the unequal fighting was that it kept Valencia glued to his front, missing a flanking force led by Robert E. Lee. The Virginian led a column of American soldiers through a ravine that skirted the Pedregal. By nightfall of August 19, and aided by a cold rain that blanketed the valley, the flanking column began to wind around the Mexican positions and gain its rear. Valencia remained unaware of their presence. Santa Anna, however, saw the American forces, yet did nothing except put a small skirmish line forward. Historian John Eisenhower wrote that the Mexican commander “was remarkably lethargic. . . he failed to attack the American between him and Valencia—a missed opportunity.” Valencia’s refusal to listen to Santa Anna began to pay dividends for the Americans, as Santa Anna’s “pique against Valencia” perhaps also added to the Mexican force not attacking down the turnpike from San Angel.[9]

The Americans woke early on August 20, around 2:00 a.m. and resumed their march to get in position behind Valencia. Around 6:00 a.m., with dawn breaking, the American forces, some three brigades’ worth of infantry, hit Valencia’s position from the rear.

Valencia’s men tried to hold their positions, but the American attacks soon had them retreating in chaos back north towards Santa Anna’s main position around San Angel. Santa Anna, who had planned to start his own offensive on August 20 instead ran into crowds of disordered Mexican forces, and furiously had to order a retreat away from San Angel. The fighting back around Padierna had taken seventeen minutes to rout the Mexican forces.[10]

The fighting on August 19-20 around Padierna caused Scott probably around 85 casualties, but in exchange they all but annihilated Valencia’s force, a crucial component of men and cannon Santa Anna relied on to defend Mexico’s capital. Mexican casualties totaled some 1,700 men killed, wounded, and captured. All 22 cannon that Valencia used to defend Padierna fell into American hands.

With the majority of operations around Contreras (Padierna) occurring on August 19, and with the objective of this 170th Anniversary being to post in real time, it may seem odd to have posted on August 20, the day with barely 20 minutes of fighting. But Padierna was just the beginning to August 20; with thousands of Mexicans in retreat, Santa Anna ordered a rearguard action to cover his withdrawal along the Churubusco River. American soldiers, flush with victory, would soon converge on the Churubusco, leading to another fight, this one far bloodier. August 20 had only just begun.

______________________________________________________________

[1] Justin H. Smith, The War with Mexico, Vol. II. (The MacMillan Company: New York, 1919), 101.

[2] Winfield Scott, Memoirs of Lieut.-General Scott (New York: Sheldon & Company Publishers, 1864), 469.

[3] Timothy D. Johnson, A Gallant Little Army: The Mexico City Campaign (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2007), 158-159.

[4] K. Jack Bauer, The Mexican War: 1846-1848 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1974) 304.

[5] Johnson 160-161.

[6] James I. Robertson Jr., Stonewall Jackson: The Man, the Soldier, the Legend (New York: Macmillan Publishing, 1997), 64; Stephen W. Sears, George B. McClellan: The Young Napoleon (New York: Ticknor & Fields, 1988), 22.

[7] Nathaniel Hawthorne, Life of Franklin Pierce: President of the United States (London: George Routledge And Co., 1853), 93.

[8] Johnson, 167.

[9] Ibid, 171-173; Douglas Southall Freeman, R.E. Lee: A Biography, Vol. I. (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1934), 263-266; John S.D. Eisenhower, So Far From God: The U.S. War With Mexico, 1846-1848 (New York: Random House, Inc., 1989), 321.

[10] Johnson, 175-176; Scott, 480.

The Mexican command friction is all too familiar to those of us who study the Civil War in the West. Not learning that lesson would cost the Army of Tennessee dearly in years to come.

Thanks for commenting. There’s definitely some parallels, even in the east. McClellan and Pope come to mind.

Thanks for keeping up with this excellent series. One thing that it hammers home: Winfield Scott must have encountered more buffoons in his career than any other officer in the Army’s history. As a young officer he was exposed to the inept likes of Brown, et al. in the War of 1812. In Mexico he had the great good luck to command such as Twiggs, Pillow, Pierce, Shields, etc. He should be saluted for winning, even against a weaker opponent with serious discord at the top.

Good observations, John. Studying and writing about the Mexican War more in depth has given me a new appreciation for Scott. He is, without a doubt, one of the greatest American generals ever.