Dranesville: A Troubled Town, Part 1

The 1st Pennsylvania Reserve Cavalry rode into Dranesville just past 5 a.m. on November 27, 1861, two hours before sunrise. Having left their camps not far from Langley, Virginia the previous night, the Pennsylvanians split up and swept into the town to carry out their mission. Knocking down doors, the troopers sought out their assignments: eleven men of the small town with arrest warrants. The Pennsylvanians managed to find six of their targets and dragged them outside. “Of all the crying and screaming that ever was heard came from the women and children, who were running around in their night clothes, pleading for us to spare their fathers, brothers, sons, husbands, etc. It was indeed, a deplorable sight,” one of the Pennsylvanians wrote.[1] And then they were gone, riding back to their camp with the arrested men in tow.

What had caused such a raid? Why at Dranesville of all places—a town so small it did not even register on the 1860 census? But, as it turns out, the arrests had not been a random occurrence: the Pennsylvanians’ raid on Nov. 27, 1861, was just another notch in a series of events centered around that town during the Civil War’s first year. Those events include ambushes, and murder, and escaped slaves; they include raids, and jail time. And, to culminate, they include the battle of Dranesville—the Army of the Potomac’s first victory. The following series will examine those events.

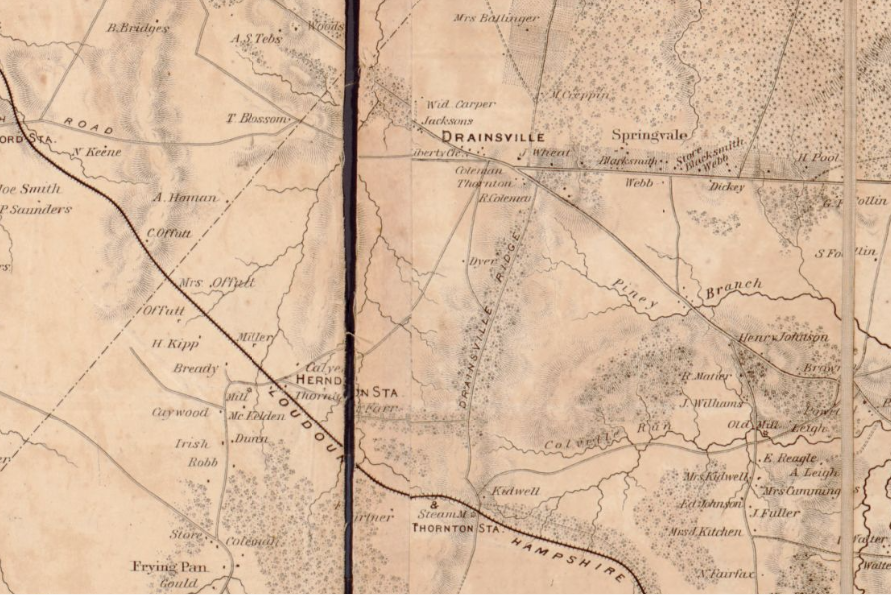

To start, an overview of the town and its occupants is in order. Dranesville is located roughly 20 miles outside of Washington, D.C., in Fairfax County, but the area got its start before the nation’s independence, and even before it had the name of Dranesville. With the city of Leesburg about another 20 miles to the west, the area that would become Dranesville presented itself as a good halfway point to stop for rests. Through the 18th century, inhabitants moved into the area, and where there are people, alcohol will follow. For the sakes of our story, Richard Coleman is the first person we can peg some significance to. Coleman opened one of the first ordinaries (taverns) in the area along the banks of a stream called Sugarland Run. By 1755, Coleman’s ordinary presented a good bivouac for some of the soldiers in Edward Braddock’s column as they made their way to Pennsylvania, with an officer remarking on the good “Indian corn, etc” at Coleman’s.[2]

(Washington Evening Star, July 21 1918)

Following the Revolution and the establishment of Washington, D.C., the area took on an even greater importance. The construction of the Leesburg & Alexandria and Leesburg & Georgetown Turnpike brought more traffic and more inhabitants. One of those inhabitants, Washington Drane, moved into the area in 1810 and soon opened his own tavern at the conflux of the two turnpikes. No matter if one left from Alexandria or Georgetown headed to Leesburg, they passed by Drane’s tavern, where he also collected the toll for the use of the turnpike. By 1825, a passerby could get dinner at Drane’s tavern for 37 and a half cents, and breakfast the following morning for another 25 cents. Dranesville became an unofficial name for the area until 1840, when the Virginia State Legislature made it official, incorporating the town.[3]

The heavy flow of traffic dried out by the late 1850s with the construction of the Baltimore & Ohio Canal, Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, and the laying of the Loudoun & Hampshire Railroad. Too small to be included as its own town for the 1860 census, the inhabitants were simply listed as living in Fairfax County, so it makes getting an overall population count difficult; Dranesville probably numbered a couple hundred people.

The small population was treated by two doctors who doubled as community leaders. Half-brothers, William B. and John T. Day lived side by side and split the town’s patients amongst them. There were also a slew of Colemans, descendants of Richard the original tavern keeper. Charles W. Coleman, for example, owned a general store about 100 yards from William Day’s house; half a mile away, Charles’s cousin Robert ran a second store and also acted as one of the area’s teachers.[4] About a mile and a half to the west of the Days lived the Carper family, who had helped develop the area earlier in the century. Also amongst the families were the Gunnells, Radcliffes, and Farrs, intermixed and mingled with marriages.

The following stories will revolve around those families—the Colemans, Days, Carpers, Gunnells, Radcliffes, Farrs, and a scattering of others. Most of them went to the Liberty Methodist Church, or to the Frying Pan Meeting House, a few miles to the south. The former had been built on land partially donated by Charles’s father, who died right before the Civil War started and whose grave now sat on a small hilltop beside the church, overlooking the town.[5] One of his sons would soon join him there, a casualty of war.

The 1860 election saw Fairfax vote mostly for John Bell, the Constitutional Union candidate, with Southern Democrat John Breckinridge close on his heels. Lincoln got 24 votes from the county’s residents.[6] Lincoln’s inauguration, as one resident of the county remembered, left “Some was pleased an’- some wasn’t.”[7]

But then came Fort Sumter. Following the bombardment, the Lincoln Administration called for 75,000 volunteers, and Virginia’s assembly, which at first proved reluctant to join the Confederacy, passed a vote for secession on April 17. That vote was to be put to the people’s approval the following month.

Thus Dranesville’s first test for war would come on May 23, 1861, when the town’s white men went to the polls.

______________________________________________________________

[1] Samuel J. Bayard, The Life of George Dashiell Bayard (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1874), 197.

[2] Norman L. Baker, Braddock’s Road: Mapping the British Expedition from Alexandria to the Monongahela (Charleston: The History Press, 2013), 31.

[3] Charles Preston Poland, Jr., Dunbarton Dranesville, Virginia (Fairfax: Fairfax County Office of Comprehensive Planning, 1974), 18; Gina McNeely, “Dranesville Tavern: The History of a Roadside Inn” in Virginia Calvacade, Vol. 43, No. 2, Autumn 1993, 74; Genius of Liberty, June 7, 1825; Richmond Enquirer, March 14, 1840. Drane’s Tavern no longer exists. A number of sources mistakenly refer to the Dranesville Tavern that still stands along Route 7 as Drane’s, but the tavern there postdates Drane’s.

[4] William Day Case File, Cases Examined by Commission Relating to State Prisoners, Record Group 59, National Archives and Records Administration, 46; Ann M. Coleman Claim, in Abstracts of Claims for Civil War Losses in Fairfax County, edited by Seth Mitchell and Edith Sprouse, page 3 of Coleman testimonies.

[5] Margaret Lail Hopkins, Dranesville Methodism (Stephens City: Commercial Press, 1984), 20-21.

[6] The 1860 Presidential Vote in Virginia

[7] Virginia Carter Castleman, Reminiscences of an Oldest Inhabitant (Herndon: Herndon Historical Society, 1976), 14.

4 Responses to Dranesville: A Troubled Town, Part 1