Dranesville: A Troubled Town, Part 4

Part 4 of a series.

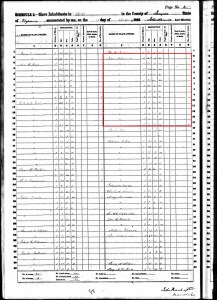

In 1860 James Coleman owned thirteen people. The oldest was 62 years old; the youngest, five months. Eight of them were females, including the baby, and five were males, and together they helped propel Coleman to a net worth of $11,000. With Coleman’s death in Jan. 1861, the thirteen-enslaved people became the property of his widow, and they continued to work on the family’s property around Dranesville.

Life kept on without much change to the Coleman enslaved people even as the war began and conflict came to Fairfax County. But then, in November, 1861, three of the Coleman enslaved people stole away, seeking out a Federal camp about twelve miles down the road from Dranesville.[1]

Their names were Caroline Jackson, Isaac Madison, and Joseph Ordwick. They were all related somehow, but records don’t say how. Caroline and Isaac were both in their twenties, and Federals didn’t note Joseph’s age, but the three of them made their way out of Dranesville and on Nov. 26, 1861 walked into Camp Griffin.[2]

Located outside of the village of Lewinsville, Camp Griffin was headquarters to Brig. Gen. William F. Smith’s division. With four brigades of infantry, Camp Griffin bristled with Federal bayonets, and Caroline, Isaac, and Joseph sought shelter there. At this early stage of the war, their fears can be surmised by looking where they went. Just four miles north of Dranesville were Federal soldiers at Seneca Falls, Maryland, including the 34th New York, profiled in the previous post. Why, then, did the three-enslaved people go three times the distance to Camp Griffin? While it’s not known for sure, they may have heard what Brig. Gen. Charles P. Stone’s policy regarding fugitive enslaved people was. Commanding the soldiers at Seneca Falls, Stone had returned escaped enslaved people to their owners, keeping in line with the still active Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.[3]

But at Camp Griffin, there was no one being returned, and the three people had a story to tell. They found willing ears with Brig. Gen. Winfield S. Hancock and Virginian John Hawxhurst. The latter was a member of what the Lincoln Administration recognized as the “Restored Government of Virginia”—Virginian Unionists who formed their own government-in-exile with its capital in Alexandria. Hawxhurst was a radical Republican, New York born Quaker, who lived “at [the] first house this side of Lewinsville” and was thus perfectly situated near the army camp to interact with the three escaped people from Dranesville.[4]

In time Caroline, Isaac, and Madison would give testimonies that filled pages worth of incriminating tales about the people of Dranesville. But on Nov. 26, with Hancock and Hawxhurst listening, they started with the names of the Dranesville Home Guard. In all, they listed eleven people, including the Day brothers, John and Thomas Coleman (sons of their former enslaver), and others.[5]

As they told the story of how the Dranesville Home Guard had ambushed the Federal soldiers at Lowe’s Island, they did get some details wrong, though—mistakes that continue to confuse today. For example, they thought the attack had taken place in August, and that it had killed two Federal soldiers. As the last post made clear, the ambush occurred in September and killed one. Because of the confusion of a man being paid to bury two bodies, a rumor started among Dranesville’s populace that two Federals had been killed. Caroline, Isaac, and Joseph likely heard that rumor and simply repeated it at Camp Griffin and after. Thus in the oft-cited Official Records are mention of two men killed, and other records mis-date the ambush to August. [6]

With their list of names, the Federals began to respond immediately. Hawxhurst forwarded the identities to Washington, and Hancock sent the three escaped people to the nation’s capital also, where they continued to testify to provost marshals.

Word soon returned from Washington that Dranesville was to be dealt with. But the order went to Camp Pierpont rather than Griffin. Named for the governor of the Restored Government of Virginia, Camp Pierpont was headquarters for Brig. Gen. George McCall’s division of Pennsylvania Reserves. Camp Pierpont was near Langley, (today where the CIA’s headquarters are), and was about equidistant from Dranesville as Camp Griffin was. But no soldier at Camp Griffin had been to Dranesville, whereas the entirety of McCall’s division had been. They had gone on a reconnaissance to the town a month earlier, where they provided security for engineers drawing topographic maps of the area, so the Pennsylvanians were intimately familiar with the area. It made the most sense to send McCall’s men.

To enter the town and arrest the men listed required speed, seeing as how close the Federals could come to nearby Confederate camps, so Col. George D. Bayard’s 1st Pennsylvania Reserve Cavalry got the assignment. They were to ride out, snatch the men listed, and ride back to camp.

Events unfolded incredibly quickly. Caroline, Isaac, and Joseph had walked into Camp Griffin on Nov. 26 and by that night, Bayard’s troopers set out for Dranesville. Part of the speed resulted in some of the more gruesome details of the story. According to the three escapees, hogs had eaten the corpses—remember their mistaken assumption of two dead—and that made the Federal soldiers’ blood boil.[7]

Bayard’s Pennsylvanians, almost 800 of them, left at 9 p.m. They “rode all night at a break-neck gait,” and closed on the town around 5 a.m. There were two Confederate cavalrymen assigned to picket the road leading into Dranesville, but both were drunk, and the Pennsylvanians captured them with ease.[8]

With no more formal opposition, the Federals struck Dranesville. They arrested their targets, and even added men who weren’t on the list, like Charles Coleman. Leaving behind wailing wives and daughters, the Pennsylvanians started to ride back towards Camp Pierpont.[9]

The raid had gone off without a hitch, but there was trouble brewing. Unbeknownst to the Pennsylvanians, their ride had not been entirely secretive. Captain William Farley, a Confederate officer, had learned of Bayard’s raid and gathered a small band of soldiers to strike the Federals as they rode to Dranesville. Among Farley’s soldiers were Philip Carper and Thomas Coleman, two men on Bayard’s list. Carper’s family lived in Dranesville and he had enlisted in the Confederate army, but Thomas Coleman still served in his capacity as a civilian irregular in the Dranesville Home Guard.

Setting themselves up in a patch of pines along the road to Dranesville, the Confederates waited. And they continued to wait. As the hours drew long during the night of Nov. 26, the Confederates gave up the hunt and retired to a nearby house for dinner and sleep. They awoke on Nov. 27 and went to return to their spot when they spotted the vanguard of Bayard’s regiment riding back towards Camp Pierpont.

As Farley remembered later, his group only had time to return to a small patch of undergrowth along the road and get into position. Bayard’s regiment rode closer, and the Confederates readied their weapons. Farley recalled that he let the Pennsylvanians get “within ten or fifteen yards,” then stood and shouted, “Now, boys!”[10]

The rifle and pistol fire hit the head of Bayard’s regiment. Bayard’s horse was killed, and two men in his regiment were mortally wounded. At first, the troopers reeled back from the suddenness of the firing, but Bayard rallied them and sent men into the pine brush. The fighting there was over really before it began, and Farley’s whole group was captured. In that quick melee, Thomas Coleman, James’s son and the enslaver of Caroline, Isaac, and Joseph, was mortally wounded. He didn’t die until later in the day of Nov. 27—after he was brought into Camp Pierpont. A Pennsylvanian remembered seeing Coleman, and wrote, “He had been shot through the head, the ball entering at one temple and coming out his opposite ear.”[11] After his death, Thomas’s body was returned to Dranesville and buried next to his father.

Bayard’s captives were forwarded to Washington and imprisoned in the Old Capitol Building. The buzz around the arrests, and ensuing fight hovered around the camp for days to come.

But it grated on the Federal high command that some of the men listed had escaped capture, and so a little over a week later another expedition was made to Dranesville. With Farley’s ambush in mind the Federals took precautions to make sure this time there would be no surprises. Instead of one regiment of cavalry, George McCall sent an entire brigade of infantry under Brig. Gen. George G. Meade.

Meade’s foray to Dranesville on Dec. 6 netted two more prisoners—John and George Coleman, cousins, who were found at their uncle’s house. They too were brought back to Washington and imprisoned, but the whole operation left a nasty taste in Meade’s mouth, who believed arresting civilians, no matter what their crime, was not something the United States Army should have been doing.

He wrote to his wife, “I never had a more disagreeable duty in my life to perform.” Meade’s expedition also netted “53 wagon loads of corn and wheat, 38 hogs. . . 11 horses, 1 yoke of oxen, buggies, chaise, harness, and a large quantity of property.”[12] Thus, even in the midst of arresting Dranesville’s civilians, Federal forces also recognized that the area around the town was ripe for taking crops, and planned further excursions.

As 1861 wound down, the events around Dranesville did not seem to be following that pattern of slowing. Rather, it was quite the opposite in the first days of December. Since April Dranesville’s populace had been locked in on a series of events that progressed more and more—from persecuting voters before the secession election, to the ambush at Lowe’s Island, to Bayard’s and Meade’s expeditions. But now Confederate forces were keyed in to how the Federals targeted Dranesville, and the Confederates aimed to reassert their control over the area while also drawing supplies from the numerous farms and homes.

The next time Federal soldiers made their way to town, it wouldn’t be just a small patrol of Confederates facing them. The battle of Dranesville, an unintended and unplanned battle, was just days away.

______________________________________________________________

[1] James Coleman Slave Schedule, 1860; James Coleman 1860 U.S. Census.

[2] Cases Examined by Commission Relating to State Prisoners, William B. Day Case, National Archives and Records Administration, 12, 17, 18.

[3] Stephen W. Sears, George B. McClellan: The Young Napoleon (Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1988), 144; L.N. Chapin, A Brief History of the Thirty-Fourth Regiment, N. Y. S. V (N.p., 1902), 22.

[4] The Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies in the War of the Rebellion ,Series 2, Vol. 2, 1286 (hereafter OR, followed by Series, and volume; Virginia Republicans, 21.

[5] OR Series 2, Volume 2, 1286.

[6] OR, Series I, Volume 5, 456; Record of Arrests for Disloyalty, 1861 and 1862, (National Archives and Records Administration), 97-98.

[7] Ibid; A soldier in Bayard’s regiment wrote that the Dranesville people “were guilty of deeds almost too horrible to relate,” giving an impression of their mindset riding to the town. Samuel J. Bayard, The Life of George Dashiell Bayard (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1874), 197.

[8] Bayard’s report, OR. Ser. 1, Vol. 5, 448; Robert Parker, Lee’s Last Casualty: The Life and Letters of Sgt. Robert W. Parker, Second Virginia Cavalry, edited by Catherine M. Wright (Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 2008), 50.

[9] Ann Coleman Southern Claims Commission, drawn from Abstracts of Claims for Civil War Losses in Fairfax County, edited by Beth Mitchell, 2.

[10] John E. Cooke, Wearing of the Gray (New York: E.B. Treat & Co., 1867), 426-427.

[11] James Chadwick Letter, Nov. 28, 1861, Allegheny College.

[12] George Meade, The Life and Letters of George Gordon Meade: Vol. 1, (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1913), 234; The Local News, Dec. 9, 1861.