The Mine Run Campaign Comes to Locust Grove

Perhaps it’s because Mine Run was, in the words of one Federal, “the great battle never fought” that so few images exist from the campaign. There was a lot of marching and moving and a fair amount of skirmishing—and participants in the affair at Payne’s Farm on Nov. 27 called it “as warm a contest as . . . was ever engaged in for the same length of time”—but the epic battle that seemed sure to erupt never did.

Perhaps it’s because Mine Run was, in the words of one Federal, “the great battle never fought” that so few images exist from the campaign. There was a lot of marching and moving and a fair amount of skirmishing—and participants in the affair at Payne’s Farm on Nov. 27 called it “as warm a contest as . . . was ever engaged in for the same length of time”—but the epic battle that seemed sure to erupt never did.

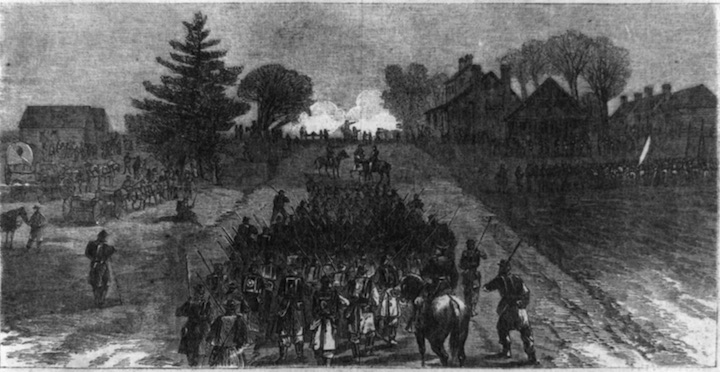

One image that does exist from the campaign shows the Army of the Potomac’s Second Corps as it marched toward Locust Grove on the morning of Nov. 27. Alfred Waud sketched the scene, which appeared as a woodcut in the January 2, 1864 issue of Harper’s Weekly on page 12.

The Second Corps marched to this point along the Orange Turnpike, on the edge of the Wilderness, as the center column of a three-pronged advance by the Army of the Potomac. At Locust Grove, the corps would rendezvous with the other two wings of the army, and then the concentrated force would push forward as quickly as possible in an attempt to flank the Army of Northern Virginia out of its position further upriver along the Rapidan.

All fall, the two armies had sparred along the axis of the Orange and Alexandria Railroad. Following the Army of Northern Virginia’s defeats at Rappahannock Station and Kelly’s Ford in early November, Robert E. Lee had withdrawn his army back along the railroad toward Orange Court House. After crossing the Rapidan, he deployed his army on the south bank to counter the expected Federal pursuit.

Rather than go straight at the Confederates, though, George Gordon Meade countered Lee’s deployment by flanking the Army of Northern Virginia’s position. One column, consisting of the Third and Sixth Corps, would cross at Jacob’s Ford. A second, consisting of the Fifth and First Corps, would cross farther to the east at Culpeper Mine Ford. The third column, in between the other two, consisted of the Second Corps, which crossed at Germanna Ford.

The three columns were to concentrate at Locust Grove and then stab into the Confederate rear, disrupting communications and logistics and forcing Lee to either withdraw from his strong position along the Rapidan or turn and fight on ground of Meade’s choosing.

The move depended on speed, though—and delays slowed the Federals’ ability to ford the river. This allowed Lee time to respond, marching his army toward the same area where Meade’s men were to concentrate.

So when the Second Corps arrived, instead of the other wings of the army, they found Jubal Early’s Confederate division bearing down on them. However, Federals held the Locust Grove intersection and the strong ridge that ran perpendicular to the road. Old Jube immediately understood his disadvantage. “A battery had been planted by the enemy on the hill at Locust Grove enfilading the turnpike, which is entirely straight,” he wrote in his report. “The enemy had greatly the advantage in position, he having got possession of the high ridge on which Locust Grove is situated. His force was concealed from view by the intervening woods except along the narrow vista made by the turnpike.”

But with the Federal army so separately, Warren did not dare press his advantage. “Though it was impossible to say how much force was near me . . .” he later reported, the situation “required caution on my part.”

But with the Federal army so separately, Warren did not dare press his advantage. “Though it was impossible to say how much force was near me . . .” he later reported, the situation “required caution on my part.”

Soon, to his left, the sounds of cannon boomed in the distance. The Fifth Corps had run into Confederate cavalry, soon backed by A. P. Hill’s infantry.

To Warren’s right: nothing.

“As soon as I get communication with General French, I intend to move forward and attack,” Warren told army headquarters, expecting the Third Corps and Sixth Corps to materialize from the north any minute. Unbeknownst to him, though, General French’s entire corps was frozen dumbfoundedly along the Jacob’s Ford Road, where they were soon to be roughly handled by Allegany Johnson’s Confederate division at Payne’s Farm.

Thus, Warren would hold the Federal center for the entire day, waiting for reinforcements that would be long in coming. The Fifth Corps would eventually arrive and bolster his position, and then, only as darkness began to settle, did Warren push his skirmishers out farther. “I am making an advance with skirmishers, only to better my position and to prevent troops being formed too near it,” he explained to headquarters.

Night, and the topography west of Locust Grove, would allow the Confederates to slip away overnight. Lee would withdraw his men to the west bank of Mine Run, a mile away, and there dig in. His defenses would become among his most formidable positions of the entire war.

On the morning of Nov. 28, Warrens’ men—now bolstered on the left and right by the missing wins of the army—cautiously advanced from their position at Locust Grove only to find the Confederates had vanished. When the advancing troops “came in sight of the valley of Mine Run, a very ugly looking line of hills had been rendered more repulsive in aspect by fallen trees and lines of freshly dug earth.” At the sight of the Confederate works, Federals settled into a new position of their own, woefully unhappy about the prospect of assaulting the Rebels.

The episode along the Orange Turnpike at Locust Grove—in front of Robinson’s Tavern (also called “Robertson’s Tavern”)—became one of the few scenes of the entire campaign captured as an image.

Today, the Orange Turnpike has been widened to four lanes, but the slope of the arrow-straight road remains the same, and the ridgeline where Warren deployed his artillery is still plainly visible. A strip mall, which seems oddly out of place in the otherwise rural Wilderness, now sits on the site of the old tavern; the original tavern building itself was moved to a nearby lot and now serves as a house.

If you compare the two images, you can still see the avenue of Warren’s approach, clear as a picture.

Enjoyable read.

Thank you!

Referring to the Harpers Weekly 1860s image, the line of soldiers on the right would be standing along a road that was part of current day Governor Almond road. From battle maps available online, I know Meade’s HQ was somewhere off of Gov. Almond but zinc just can’t figure exactly where, not enough detail and error in the maps.

Chris, I’m surprised you don’t mention in your articles the fact that Robertson’s Tavern still stands near the historic intersection at modern day Locust Grove. The historic tavern and key landmark currently sits just north of the Exxon station–a few yards from where it stood in November 1863. It was moved sometime after the war — but still survives!!

My apologies – you do mention it above. I guess I was hoping for a current photo.

I’ll try and post one for you later today.