Confederate Monuments in Massachusetts: Who knew? (Part 2)

Emerging Civil War welcomes back guest author Rob Wilson

Emerging Civil War welcomes back guest author Rob Wilson

Part 2 (Part 1 is available here.)

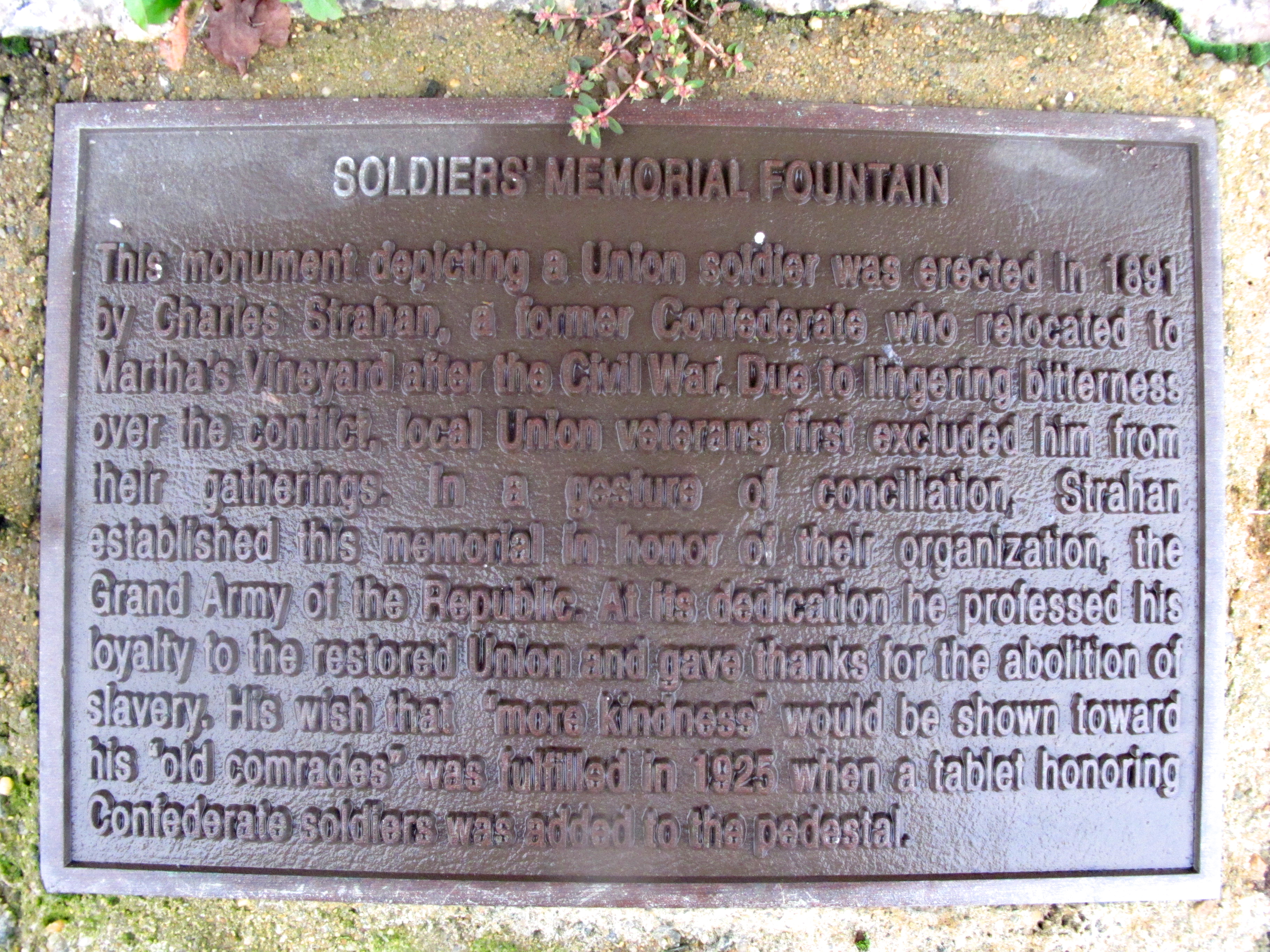

The story of how a memorial to Confederate soldiers landed on Martha’s Vineyard in 1925 actually begins in 1891. That’s when the Soldiers’ Memorial Fountain, topped by a zinc statue of a Union soldier, was erected in Oak Bluffs to honor members of the island’s chapter of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), the preeminent organization for federal veterans of the Civil War. It is to that monument’s cast iron base that the tablet was affixed, among three existing plaques honoring GAR members. That plaque— declaring itself “In memory of the restored Union” and “in honor of the Confederate soldiers”— was installed with the support of the GAR’s surviving veterans and many other local citizens.

The fact that the Confederate plaque resides on a Union monument partly accounts for its acceptance. Yet there are deeper reasons it has avoided the kind of controversy that doomed the Fort Warren memorial, reasons contained in the remarkable and intertwined stories of Civil War veteran Charles Strahan and the monument. It was he who proposed and ultimately financed the statue. An Oak Bluffs resident for seven years at the time that memorial was dedicated, he had much in common with the federal veterans who enthusiastically backed his idea to erect a monument. Save one extraordinary difference: during the Civil War, this veteran fought for the Confederate States of America.[i]

Stranhan had been living in the loyal Union state of Maryland when the war started. A secessionist sympathizer, he joined the Maryland Guards, a militia unit with Confederate leanings that was absorbed into the 21st Virginia Infantry Regiment, Army of Northern Virginia. Wounded in the summer of 1862, at the Battle of Seven Pines, Strahan was discharged. Once recovered, he reportedly re-enlisted in the ANV and remained in service the rest of the war. By one record, he was a lieutenant on Maj. Gen. Isaac Trimble’s staff at Gettysburg.

Nearly 20 years after the war ended, the veteran moved with his family to Oak Bluffs, bought the town’s newspaper and renamed it the Herald. Eventually accepted by most of his new neighbors, Strahan’s outreach efforts to GAR members were unsuccessful. However, he persisted and, after years, his attempts to connect won over several federal veterans. One of those men wrote a letter-to-the-editor at the Herald, pressing his comrades to accept “a certain long-ago Confederate officer (now a worthy, law-abiding resident of our Island city).”

The proposal to build the monument followed, the publisher offering to cover its costs by donating part of his paper’s subscription fees. The GAR’s Henry Clay Wade Post subsequently invited him to speak at a Memorial Day ceremony. The Union veteran introducing Strahan asserted that “[he] has proven his loyalty to Martha’s Vineyard, and especially his loyalty to our Post…” Asked to speak, the one-time Confederate soldier shared his feeling that “the mists of prejudice which have hung like a cloud over me, in this, my adopted home, are fast disappearing under the sunlight of your affectionate and brotherly hearts.”[ii]

As the monument project approached conclusion, the expatriate southerner reportedly donated $500 of his personal savings towards a shortfall in its budget. At the monument’s dedication, on August 13, 1891, Strahan’s five-year-old daughter pulled off the American flag shrouding the statue. Speaking to a large and enthusiastic crowd, the veteran reportedly “gave thanks for the abolition of slavery,” a remarkable public statement for a white southerner to make in the post-reconstruction era. He also shared his vision of a reunited nation: “That this comes from one who once wore gray I trust will add significance to the fact that we are once more a union of Americans, a union which endears with equal honor… that Massachusetts and South Carolina are again brothers; that there is no North nor South, no East nor West, but one undivided, indivisible Union.”[iii]

A time after the dedication, Strahan wrote of a dream he had for the monument’s future. Paraphrasing words Stonewall Jackson uttered on his death bed, the one-time Confederate soldier shared his hope that the island’s federal veterans someday might place on the statue “a token of respect to their old foes in the field, who have passed over to the other side of the river and are resting under the trees.”[iv]

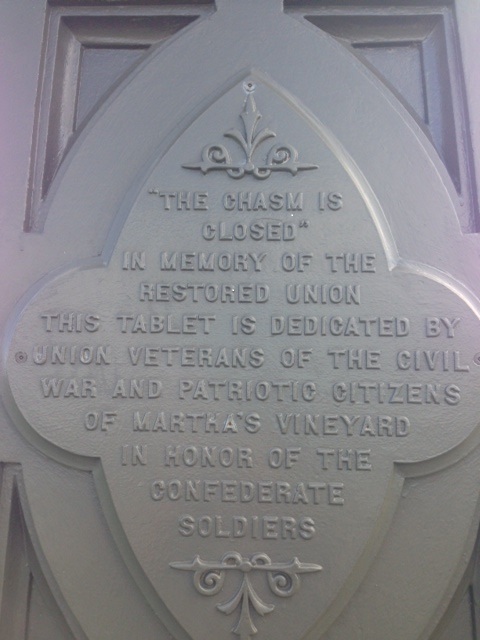

Thirty four years later, in 1925, the Vineyard GAR’s few surviving members banded together to honor Strahan’s wish. A new plaque was affixed to the monument’s base and unveiled at a well-attended ceremony. “THE CHASM IS CLOSED,’” it reads, declaring: “IN MEMORY OF THE RESTORED UNION THIS TABLET IS DEDICATED BY UNION VETERANS OF THE CIVIL WAR AND PATRIOTIC CITIZENS OF MARTHA’S VINEYARD IN HONOR OF THE CONFEDERATE SOLDIERS.”

Eighty-six and frail, Strahan was unable to attend the ceremony. A dedication speaker noted his absence, remarking in her speech that the time had come to honor “our ex-Confederate soldier.”[v]

Fast forward to last August, just after Charlottesville’s monument-related violence. Contrasting the Soldiers’ Memorial Fountain to the controversial statue in that southern city, an editorial in the Martha’s Vineyard Gazette posited the island memorial expressed “an aspiration that is as urgent today as it was when it was unveiled in 1891: to heal a nation’s deep divisions.” The monument‘s message, the editor continued, “couldn’t be more different than that of the Confederate statues [that symbolized] resistance to efforts to end Jim Crow laws and other forms of racism.”[vi]

Not all Gazette readers agreed. Some letters-to-the-editor at the Gazette and the Martha’s Vineyard Times were critical of the plaque, asserting a recognition of Confederate soldiers had no place in Oak Bluffs, given its black heritage. Several letters linked the monument to the reconciliation movement. This post-Reconstruction school of thought, common in both North and the South, ignored vital details of the Civil War, such as the triumph of emancipation and the horrors of slavery, instead focusing on themes such as loyalty to one’s cause, heroism, and North-South reconciliation.[vii]

Defenders of Charles Strahan and his Soldiers’ Memorial Fountain responded, both on line and on blogs, some noting that the southerner had publicly given thanks for slavery’s abolition and that symbols and code words for the Confederacy and the Lost Cause are absent on the tablet. The monument, one wrote, embodied the unity and healing Lincoln intended when he spoke of binding the nation’s wounds in his Second Inaugural speech. Another interpreted the monument project as part of a Strahan’s “lifelong effort to mend” a heart wounded by war, and a sincere declaration of loyalty to a Union restored.[viii]

Despite the heartfelt criticisms, the monument debate appears to have ebbed. For example, there were no monumental arguments among the audience members crowded into the Martha’s Vineyard Museum for a late August program that examined the history of the Soldiers’ Memorial Fountain and discussed how it fit into the national monument debates. Called in October, the office manager in the Oak Bluffs Town Administrator’s Office reported only one complaint about the plaque to the town. But the island resident who had scheduled time on the Selectman’s September meeting agenda to propose removal of the memorial, subsequently canceled his appearance.

The critics of the Soldiers’ Memorial Fountain and its tribute to Confederate soldiers are not likely to go away. Nor will those who have been moved by the story of Charles Strahan, a man who once served the Confederacy, settled on the Vineyard and embraced island life, launched a successful campaign to close the chasm that separated him from Union veterans, inspired a monument to a reunified Union and gave thanks for slavery’s abolition. They might compare the Vineyard’s little-known monument to the famous Eternal Light Peace Memorial in Gettysburg, commemorating the 75th anniversary of the battle. Dedicated on July 3, 1938, that towering structure also honors the soldiers of North and South and celebrates a reunited nation.[ix]

As he dedicated the monument, speaking to a Gettysburg audience estimated at a quarter million, President Franklin D. Roosevelt expounded the very themes Strahan had enunciated at his monument’s 1891 unveiling.

“All of them we honor,” FDR said of the veterans of the Civil War, his words broadcast on national radio. “[Not] asking under which Flag they fought then thankful that they stand together under one Flag now.”[x]

Thanks to Tom Hodgson, a Martha’s Vineyard resident and a descendent of Charles Strahan, for providing information and photographs for this series of posts. To view a piece he posted on his blog about the Soldiers’ Memorial Fountain, go to https://thetompostpile.wordpress.com/2012/10/09/charlies-statue/

[i] Tom Dunlop, “Uniting the Divided: A Civil War monument in Oak Bluffs honors both Confederate and Union soldiers,” Martha’s Vineyard Magazine, 8/2013, http://www.mvmagazine.com/news/2013/08/01/uniting-divided Accessed 8/18/2017.

[ii] Martha M. Boltz, “Peacemaking long after last shot,” Washington Times, 8/22/2005, http://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2005/jul/22/20050722-085343-9433r/ Accessed 9/2/2017;

Tom Dunlop, “Uniting the Divided: A Civil War monument in Oak Bluffs honors both Confederate and Union soldiers.”

[iii] Quotation taken directly from the Soldiers’ Memorial Fountain Plaque; Dunlop, “Uniting the Divided;” Boltz, “Peacemaking long after last shot.”

[iv] Dunlop, “Uniting the Divided”

[v] Boltz, “Peacemaking long after last shot”

[vi] Martha’s Vineyard Gazette, Editorial Page, 8/17/17 https://vineyardgazette.com/news/2017/08/17/monument-healing

[vii] Ibid.; David W. Blight, Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American History (Harvard University Press, Cambridge Mass., 2001), 4, 9-11.; Brian Matthew Jordan, Marching Home: Union Veterans and Their Unending Civil War, (Liveright Publishing, New York, 2014), 88-90, 104.

[viii] Martha’s Vineyard Gazette, 8/17/17

[ix] Steve A. Hawks,” Eternal Light Peace Memorial,” 2017, Gettysburg/Monuments, http://gettysburg.stonesentinels.com/other-monuments/eternal-light-peace-memorial/

[x] Franklin D. Roosevelt, “Speech of the President: Gettysburg, July 3, 1938,” Civil War Trust, https://www.civilwar.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/fdr-gettysburg-speech2.pdf .

Interesting article. Also interesting is the contemporary zeitgeist of destroying whatever you don’t agree with. And…. that the Vineyard wanted to secede from Massachusetts in 1977.

Thanks for your comment, David. I remember the “Mouse That Roared” secessionist fever that flared up on the Vineyard back in 1977. Your reply inspired me to look back on the news coverage. Go to http://www.nytimes.com/1977/04/06/archives/massachusetts-isles-wave-secession-flag.html for the story.

Excellent and timely article.

Thanks for your kind words John.

Who knew, indeed! Thanks for the contribution, Rob. Sounds like the “monumental argument” was quelled by good old-fashion Yankee stoicism.

Thanks Chris. In addition to “Yankee stoicism,” I think a good dose of local pride in Strahan’s remarkable and very unusual story put a damper on the argument. That said, there are islanders, too, who strongly feel the plaque should be removed or altered.

Just a little history note from a Marylander. There is a book titled, ” A Southern Star for Maryland and the Secession Crises”, written by a John Hopkins faculty member by the name of Lawrence M. Denton. Maryland was far from the loyal union State as mentioned in this article and had she not been invaded, she would have joined her sister states of the CSA. How ironic that when invaded, members of Francis Scott Keys family were imprisoned as southern sympathizers.

Thanks Robert, for that interesting fact. I knew there was a lot of sympathy for the Confederate cause in Maryland, but I didn’t know of Denton’s assertion that the state came that close to secession. I believe, however, that Marylanders did not rise up in mass, as Robert E. Lee had hoped they would when Confederate forces invaded. Perhaps the desire to join the Confederacy that Denton identified ebbed as the war progressed?

One reason that they did not rise up in mass is because the president suspended habeas corpus, allowing northern troops and federal officials to arrest those who expressed southern sympathies and to seize private property. Having already been occupied, it was quite intimidating when threatened with the loss of your rights under the Constitution, the Bill of Rights your liberties and property.