Christmas Arrives in January at a Washington D.C. Camp of Instruction

Emerging Civil War welcomes back guest author Rob Wilson

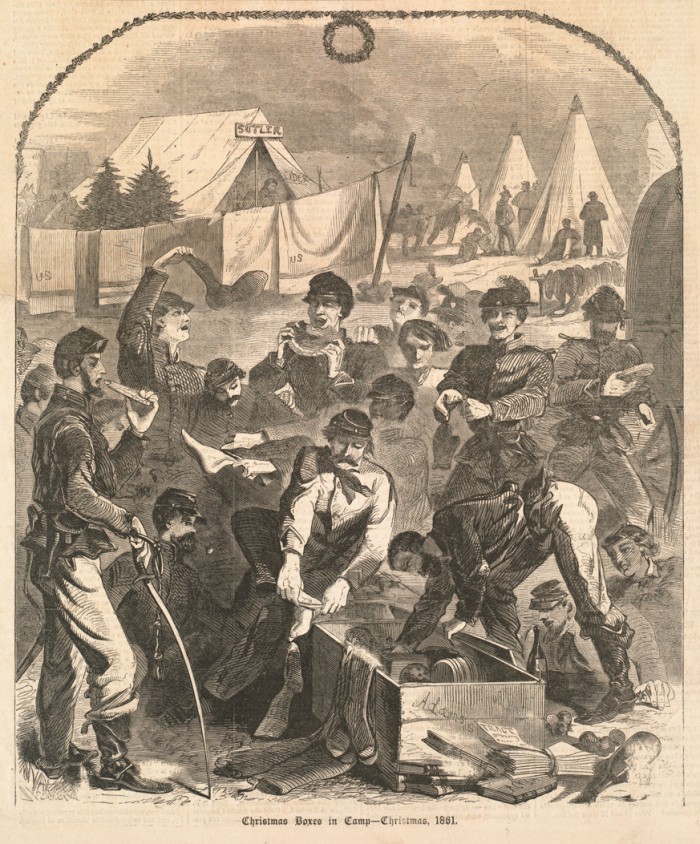

Illustration by Winslow Homer that appeared in Harper’s Weekly (Library of Congress).

Combing through my great grandfather’s Civil War letters for a holiday season story, I learned how, in 1861, he celebrated Christmas in January. That year George A. Marden was a fresh volunteer in the Army of the Potomac on December 25, and just a month into his training at the U.S. Sharpshooter’s Second Regiment Camp of Instruction in Washington, D.C. The letters home— which were saved by his parents, back in Mont Vernon, N.H.— have been passed down to me through my family.

By multiple newspaper accounts, this Christmas was a joyous occasion for most of the tens of thousands of Union soldiers training for war in 1861 at the Army of the Potomac camps in and around Washington, D.C. The weather leading up to the day had been miserable, but Christmas morning dawned “with all the beauty of a Pennsylvania May Day,” wrote a Philadelphia Press reporter. The Keystone State troops he visited that day had been excused from drill and were busy decorating their camp. “Our boys… had quite a jovial time, all things considered,” he wrote.[i]

From the tone of his Christmas day letter, however, Marden had not joined in the camps’ general merriment and was feeling pretty blue. The 22-year-old from the tiny town of Mont Vernon had volunteered for the Sharpshooters in November. That month he and his Company G comrades— all boys from southern New Hampshire—had traveled some 500 miles by train and steamship to their Camp of Instruction. The fresh recruit was spending what likely was his first holiday season away from family and friends. In his letter of December 25, he wrote of missing his usual snowy New England Christmas at home. Yet homesickness was not the only reason for the soldier’s low spirits.

Despite the warming sunshine bursting forth on the 25th, the month of December had delivered its share of icy and wet days to the capital city. The soldier wrote that the harsh conditions were making camp life extremely difficult.

Despite the warming sunshine bursting forth on the 25th, the month of December had delivered its share of icy and wet days to the capital city. The soldier wrote that the harsh conditions were making camp life extremely difficult.

Our rain storm cleared off in a snow squall and came out in a gale of wind and cold snap… I seldom have heard the wind blow harder, and it froze up tight. You may imagine that a tent would not be the most comfortable place in which to pass the night. I confidently expected every moment that the tent would leave us. We could keep no fire for our stovepipe chimney blew down, and I have not passed such a disagreeable night on the ground. Those who had fireplaces were even worse off, for the wind drove the fire all over the inside of the tents and came near causing a general conflagration.[ii]

The storm, he continued, blew down two hospital tents, leaving the sick inside exposed to the wind and cold. “In our Reg. the 2nd, of 700 men 150 are on the sick list,” Marden wrote. “Two men died night before last.” Just the week before, the soldier had visited one of the unfortunate soldiers— a Sharpshooter from New Hampshire he knew— as the man lay in his tent, on a bed of straw, suffering from measles and a bad cold and cough.

After describing a ration of raw salt pork he had been issued to fry or boil on his own because his company’s cookstand had been damaged badly in the storm, the lonely Private Marden concluded his woeful eight-page letter with an epicurean fantasy. “I should like a Christmas dinner from home and a few fried sausages if I didn’t have to pay the express.”

His letters do not indicate whether the Sharpshooter actually expected his family to grant his wish. But sixteen days later, on January 10, a substantial collection of holiday gifts from Mont Vernon arrived, packed in a barrel and addressed to Private George Marden. The delivery— which included a variety of food items that could be considered sumptuous by our own 21st Century standards— apparently caused quite a stir in the Second Regiment camp. Here is my ancestor’s account of the event, which brought some belated Christmas cheer to a day that was “wet and nasty… so it continues just foggy and drizzling and mud ankle deep.”

My Express barrel arrived at half past three in the P.M. To say that I was tickled wouldn’t to begin to express it. So it came off the wagon a dozen of the boys clamored around me to help carry it to our tent, eager and noisy… I manned the hatchet and commenced my first assault in a military capacity. I am proud of the success of my charge… The Sausages came out all straight in one sense, though crooked enough in another. The brown bread took best… I distributed a slice and a link to some of my particular friends and the way it brought New Hampshire to their minds was gratifying. Some jumped right up and down. The sponge cake was delicate and sweet and was a fitting addition to the rest. The baked chicken brought up the rear, and filled the post as bravely as Marshal Ney in Russia.* I don’t forget the cheese which like all the other things was excellent and in excellent order.”[iii]

Marden wrote that he shared much of his food with his enlisted Company G comrades, and delivered a portion of the “rear guard” chicken to a sick friend from New Hampshire soldier in another regiment. He also carried “a piece of the cake, a few of the sausages and a part of the brown bread” to one of the captains with whom he was friendly, perhaps hoping to bolster his chances for the promotion to sergeant towards which he’d been working.

“I didn’t get any more than taste the things for I got enough to eat and ‘the boys’ needed it all,” he continued. “I can’t tell which they were most pleased with, but you may all rest assured that everything was thankfully received.”

The bounteous barrel also contained some practical items that Marden especially appreciated. “I was most pleased with the clothing, and visions of clean shirts, clean collars and a pair of boots I could wear pleased me more than all the edibles,” he gushed. “When I realized them all this morning, I came out a new man.”

The soldier knew well that the cost of the various purchases and the shipping of the express barrel constituted a considerable expense for his parents. The gift of boots “I could wear” (as opposed to his uncomfortable government-issued footwear) were, to Marden, a treasure. They were made by his father, who owned a small shoemaking facility and shop in Mont Vernon. George had worked there when he was not in school, and his wages helped to fund his college education.

As he continued his winter training in Washington during January and February, the cold and miserable weather slowly would improve. Yet, challenges of a more desperate and deadly variety awaited on battlefields in Virginia, Maryland and Pennsylvania. For Marden, those risks would commence when he was promoted to sergeant, transferred to the U.S.S.S. First Regiment staff, and shipped to southern Virginia for the Peninsula Campaign. But the Sharpshooter, like so many of his Army of the Potomac comrades, would weather war’s cruel hardships and carry on. Letters and the occasional packages received from home—arriving at Christmastime or anytime— would play an essential role in boosting the soldiers’ morale through the Civil War’s darkest moments.

* Ney had been a leader in the French army, and was well-known in Marden’s time. The Marshal’s command of the retreating French rear guard is credited with saving Napoleon’s forces from annihilation during their disastrous 1812 invasion of Russia.

[i] Philadelphia Press, Dec. 27, 1861

[ii] The Civil War letters of George A. Marden, Dec. 25, 1861 (Archived at Rauner Library, Dartmouth College, Hanover N.H.)

[iii] Ibid., January 10, 1861

What a treasure these letters are. You can just hear the eagerness and appreciation in his words, and the mention of bringing “New Hampshire to their minds” with brown bread and sausages says volumes about Union soldiers far from home. Thanks for this post. Anyone have a recipe for brown bread?

Thanks Meg. Unfortunately, my great great grandmother did not include her brown bread recipe when she passed George Marden’s Civil War letters down through my family. But do not despair! There is an authentic Civil War recipe for Yankee Brown Bread at http://www.geniuskitchen.com/recipe/yankee-brown-bread-297096. Enjoy!

Rob–Now Mr. Place and I can both make Yankee Brown Bread! Huzzah! and thanks.

Meg: You are welcome. Glad to share the recipe. If you decide to bake up some Yankee Brown Bread, feel free to ship it express barrel (as George’s mom sent it to him, at camp). I also would gladly accept a baked chicken, cheese, sausages, etc. and on your way to the post office, why not pick me up a pair of size 12 brogans, just like George’s? 🙂

Thank you .will use some of this in our program we do here every month . this month winter in camp

Thanks for your thanks, Thomas. I’m glad you can use my post for your winter camp program. Hopefully you’ll have better weather than George Marden did!

What a great collection. Letters (and stories) like these make me appreciate the things I have, like a roof on my head during a storm and good clothes when I need them. Great share.

Thanks M.B. Your testimony to 20th Century conveniences is well taken. After reading my ancestor’s accounts of the cold, heat, disease and medieval medical practices he endured during the Civil War– which the found as dangerous as fighting the war– I too am glad to be living in modern times.