“I am a poor colored soldier…” – Finding Private Anthony Wren

ECW welcomes back guest author Jon-Erik Gilot

Several years ago the historical society in my hometown of Mount Pleasant, Ohio, received a donation of books, photographs, and papers relating to Pinkney Lewis Bone. Bone was something of a local celebrity in Mount Pleasant, having served as a drummer and stretcher bearer in the 52nd Ohio Volunteer Infantry. He returned home to open a grocery store in a ca. 1803 log cabin and lived into the 1930’s as one of the areas last surviving Civil War veterans. Some of the village elders still recall seeing Bone riding in the back of a car in the Memorial Day parade. Today, his cabin is owned and operated by the historical society.

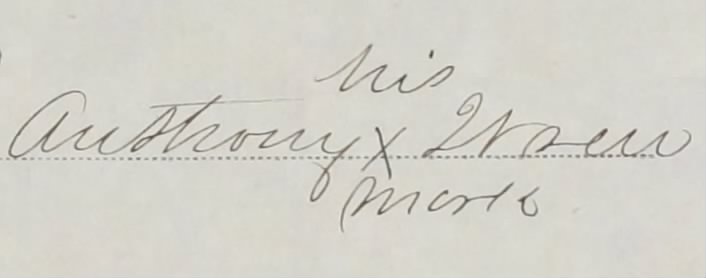

Among the material donated was a print from a ca. 1895 glass plate showing Pinkney Bone standing proudly in front of his store along with his wife and several children. What struck me most about the photo was not Pinkney Bone or the store, but the slightly out-of-focus individual in the bottom right corner. It was likely happenstance that he appeared in the family photo, perhaps just walking down the sidewalk at just the right time. Thankfully, his name was preserved on the photo along with each of the Bone family members. Here’s a better look…

Though difficult to make out, the name reads “A. Wren.” Having spent more than two decades researching our local Civil War soldiers – particularly our African American soldiers – the name jumped off the page. For the first time, I could put a face to one of Mount Pleasant’s African American Civil War veterans. Armed with a name and a face, I set out to learn more about Anthony Wren.

Though difficult to make out, the name reads “A. Wren.” Having spent more than two decades researching our local Civil War soldiers – particularly our African American soldiers – the name jumped off the page. For the first time, I could put a face to one of Mount Pleasant’s African American Civil War veterans. Armed with a name and a face, I set out to learn more about Anthony Wren.

Mount Pleasant was something of an anomaly in 1860. The small village of 1,600 residents in eastern Ohio, located just a few miles from the slave market in nearby Wheeling, had become a safe haven for runaways and freed African Americans, so much so that a full 15% of the village population in 1860 was African American. Edwin Stanton’s grandmother, Abigail Stanton, had brought her freed slaves to the area in 1800, granting each a piece of property to farm. The predominantly Quaker population was active in any number of abolitionist activities, ranging from the earliest antislavery publications in the United States (The Philanthropist, published in Mount Pleasant by Charles Osborne in 1817) to a bustling “Free Labor” store, where nothing produced by slave labor was sold. A number of local residents were likewise active on the Underground Railroad, shuttling runaways across the Ohio River and north to freedom. Many former slaves opted to remain in Mount Pleasant, feeling safe among the Quaker population. Anthony Wren could be counted among that number.

According to the 1900 census, Anthony W. Wren (an additional ‘n’ is alternately used on several documents) was born in January 1828 in Virginia. We don’t know his parents’ names nor where exactly in Virginia he was born, though it’s possible he hailed from Southampton County, Virginia, the child of or descendant of slaves freed by Richard Wrenn, a Southampton Quaker who manumitted his slaves in 1783. Richard’s son, William Wrenn, would later seek permission from the Gravelly Run Monthly Meeting to travel to eastern Ohio and view the prospects of the growing population there. Given the exploding violence in Southampton County with the 1831 Nat Turner rebellion and the subsequent slaughter of approximately 200 innocent African Americans, it’s possible that Anthony’s parents decided to head out to Ohio themselves. Whatever the circumstances may have been, we know that by 1860 Anthony Wren was living in Mount Pleasant, Jefferson County, Ohio, where he worked as a farmer.

In August 1864 an army recruiter arrived in Mount Pleasant and set up shop in the AME Church in hopes of enlisting some of the local African American population for the war effort. More than a dozen men from the village enlisted, complementing the nearly two dozen others who had earlier enlisted in the 55th Massachusetts, 5th USCT and other regiments. Among that number was Anthony Wren. These men joined nearly two dozen more enlistees from neighboring Barnesville, Ohio, and transferred to Camp Delaware, Alliance, Ohio, where they officially mustered into federal service for a term of one year.

Wren and the others waited for their regimental assignment as the camp swelled to nearly 400 men, at which point they were transferred to Nashville, Tennessee, to form the nucleus of the 9th United Stated Colored Heavy Artillery. Wren and the other men from Mount Pleasant were assigned to Battery D, and while designated as heavy artillery, would function as infantry for the duration of their service. The regiment was assigned to the Department of the Cumberland to serve as laborers.

Battery D was stationed near Nashville at Camp Foster, which had been established as a point of rendezvous for African American recruits as well as a place to gather the hundreds of contraband streaming into the Federal lines. Tasked with constructing breastworks and improving defenses, Wren became debilitated with rheumatism, the pain in his legs and arms plaguing him for the rest of his life. By December, Battery D was relocated to make repairs at Fort Houston and neighboring Fort Negley. During the Battle of Nashville on December 15 – 16, 1864, the men marched out of their winter quarters, and, exposed for more than a week without shelter from the weather, a number of men fell ill. Anthony Wren again became debilitated with rheumatism and measles. The battery spent the remainder of the winter and following spring performing manual labor around Nashville.

In a deposition found in Anthony Wren’s pension file, one of his comrades testified that during the summer of 1865 while on battalion drill in Nashville, the men were ordered to run at double-quick time. Wren and several others were overtaken with the heat and exhaustion and were trampled by the men running behind them. Wren was carried to the hospital, complaining of a rupture and pain in his bowels. He was placed on light duty until July 1865 when the regiment was broken up and the men transferred to a number of different regiments. Wren found himself in Company I 100th United States Colored Infantry, joining the regiment at Sneedsville, Tennessee. His comrade again testified that Wren continued complaining of pain in his legs and spent much of his time in the hospital, from which he would be mustered out on September 14, 1865, having served a little more than one year.

Wren returned to Mount Pleasant to continue work as a modest farmer. He married four times and fathered one son who did not live to adulthood. The 1880 census shows Wren as “sick,” a likely indication that he never fully recovered from his war service. The 1890 veteran’s schedule likewise notes him as suffering from rheumatism and a rupture. In June 1883, he filed for an invalid pension. Depositions collected from his comrades, neighbors, and associates testified that Wren had entered the service an able and healthy individual and was discharged a broken man. Several remarked how Wren was often confined to his bed, while others recalled hearing him complain of severe pain in his bowels while shoveling or doing heavy lifting. Wren said it best himself, while dictating to his pension agent – “I am a poor colored soldier and am so disabled I cannot make a living for my family.” He was rewarded with a modest pension for the remainder of his life.

In 1885 Wren became a charter member of the Jonathan Taylor Updegraff Post No. 549 of the Grand Army of the Republic, one of only two known integrated posts in the upper Ohio Valley. He participated in Decoration Day activities and enjoyed some stature within the community until his death on December 12, 1903. He was buried in a remote corner of Short Creek Cemetery in Mount Pleasant, an area today heavily overgrown and nearly one hundred yards from the nearest marked graves. His headstone makes no mention of his military service and is quickly weathering,

Nearly 180,000 African American men served in the Union army during the Civil War. Few left us with letters, diaries and photographs to document their service. Many remain faceless in forgotten cemeteries with pension files waiting to be explored. While his headstone may fade, Anthony Wren is faceless no more.

Mount Pleasant, Ohio

Jon-Erik M. Gilot, Director of Archives & Record for the Diocese of Wheeling-Charleston, is a 2006 graduate of Bethany College with a Bachelor of Arts in History and a 2011 graduate of Kent State University with a Master of Library and Information Science. Prior to his current position, he spent time working at the Library of Congress as well as a Pittsburgh-based preservation firm. A native of Mount Pleasant, Ohio – birthplace of abolitionist printing and focal point of Underground Railroad activity – Jon-Erik has spent more than two decades researching and writing on the Civil War era. He was a member of the Wheeling Civil War Sesquicentennial Committee and a contributing writer for the 2015 book “Wheeling During the Civil War.” He is a board member of the West Virginia Independence Hall Foundation; a Wheeling Historic Landmarks commissioner; and a frequent lecturer on Civil War and archival topics.

This is a great article. I am glad the author has taken the time to research the many black soldiers, particularly from Eastern Ohio (I am from St. Clairsville), who fought in the Civil War. Great work about a courageous group of soldiers.

A very good.read. Very enlightening

A very good article. It would be wonderful…. if Mr. Wren had a new grave marker,

and his grave site cleaned up.

You did some great history detective work to fill out and share this previously untold story. What an interesting narrative of the patriotism of black soldiers and the weathering the health hazards and challenges of Civil War military service! Good work and thanks. Your use of town and county records (and photographs) might inspire others of us to search those kinds of resources for the stories of individual veterans who remain, in your words, “faceless in forgotten cemeteries with pension files waiting to be explored.”

Excellent article. I have African American family members that lived in Mt. Pleasant…Lydia Bryant(Mason, Allen). She married Henry Mason and moved to Mr. Pleasant in approx. 1868. When Henry died, she married William Allen, who, I believe was native of Mt. Pleasant and was a soldier in the Civil War.) I am trying to find out more about her and her husbands. Pictures would also be welcomed.