Slaves and Sailors in the Civil War

The enlistment of African Americans as soldiers in the United States Army during the Civil War is a well-examined topic, but less appreciated is the story of freedmen and former slaves as sailors in the navy.

The enlistment of African Americans as soldiers in the United States Army during the Civil War is a well-examined topic, but less appreciated is the story of freedmen and former slaves as sailors in the navy.

Wartime experiences of these men (and a few women) are as distinct as the environments—ashore or afloat—in which they served.

Men of African descent in the sea service started out ahead of their land-bound compatriots and benefited from vastly expanded wartime opportunities.

But they did not significantly advance the conditions of service, finishing the war about where they started in better-than-slavery but less-than-equal circumstances.

In the army, African Americans achieved a monumental step forward, a tale of stoic sacrifice and daunting perseverance in the pursuit of freedom and equality as depicted in the popular movie Glory.

Starting from total exclusion—the federal Militia Act of 1792 outlawed their services—African-American soldiers sweated, bled, and died their way to broad acceptance as combat soldiers. They escaped bondage and approached equality at least in the enlisted ranks only to have that promise snatched back postwar to the muddy middle ground of segregation and circumscribed citizenship.

The navy always had been racially integrated; there were no laws like the Militia Act. African Americans hazarded their lives and freedom against the nation’s enemies in the colonial and United States navies while achieving a level of respect, relatively fair treatment, and economic opportunities generally not available ashore.

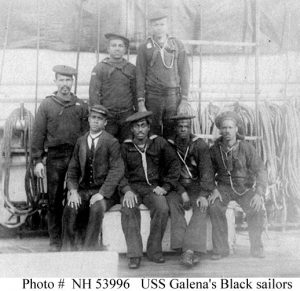

They were fully integrated into ship’s crews. Although performing primarily manual and service functions, they were not restricted to those roles. They equally manned the big guns, were trained in small arms, and performed the myriad of seamanship duties expected. With persistence and performance, African Americans could attain petty officer (non-commissioned) positions equivalent to crewman of European descent and were paid accordingly.

Through the quasi war with France, the War of 1812, and the Mexican War, economic growth and westward expansion generated continuing shortages of merchant sailors for the navy to recruit. Restrictions on enlistment of foreigners and general bias by mariners against navy service created increased opportunity for African Americans. Such service also generated controversy, adding fuel for antislavery advocates in the debates on the meaning of liberty.

Commodore Isaac Chauncy wrote of his African-American crewmen during the War of 1812: “To my knowledge a part of them are not surpassed by any seamen we have in the fleet; and I have yet to learn that the color of the skin…can affect a man’s qualifications or usefulness.” He had nearly fifty onboard and considered many of them among his best men.[1]

Commodore Oliver H. Perry praised the bravery of his many African-American crewmen after the crucial battle of Lake Erie in September 1813. Captain Isaac Hull, commanding the USS Constitution (Old Ironsides) in her desperate struggle with HMS Guerriere concluded: “I never had any better fighters than those n—ers. They stripped to the waist & fought like devils, sir, seeming to be utterly insensible to danger & to be possessed with a determination to outfight white sailors.”[2]

While African Americans faced hardship and death alongside shipmates, such service did not materially improve their lives ashore, and peacetime efforts were made to exclude them from the navy. Navy Surgeon Usher Parsons recorded that they made up a tenth of the crew of the frigates USS Java and the USS Guerrier. “There seemed to be an entire absence of prejudice against the blacks….” That was not entirely true but still it applied much more often than on land.[3]

The navy at sea was its own world with its own authoritarian structures, customized through millennia to the unique needs of shipboard life and hardly less strict in its way than slavery. Officers were immersed in a cosmopolitan service accustomed to sailors of all shades and always desperate for men.

It would have been disruptive of efficiency and discipline to place some into a separate category based just on color and treat them differently, and there was no need to. While this was still very much a class system, the qualifications of race, which played such a central social and economic role on land, had little importance at sea.

The policies of the United States Navy changed drastically in the nineteenth century, eventually leading to a career enlisted service. After decades of resistance by traditionalists, including many seamen, the ancient practice of flogging was abolished in 1850. The measure to end service of alcohol or grog was passed on the day after the battle of Antietam, September 18, 1862.

These measures reflected the social crusades of the second Great Awakening. Seamen’s welfare resonated with many other issues of that socially conscious era, including slavery, and led to significant improvements in the conditions of both merchant and navy sailors.

African Americans continued to enlist in substantial numbers through the 1820s and 1830s, although regulations from the 1840’s onward limited their numbers to 5 percent of the enlisted force. Southern officers increasingly brought slaves afloat or enlisted them and collected the salaries.

As the issues heated up, Northern political backlash led to severe restrictions on employment of slaves. At the same time, economic hardship was forcing many other men back to sea taking available berths. African Americans constituted only about 2.5 percent of the enlisted force in spring 1861.[4]

As the war exploded so did the navy. African Americans recruits were mostly freedmen at first, many having naval or maritime experience.

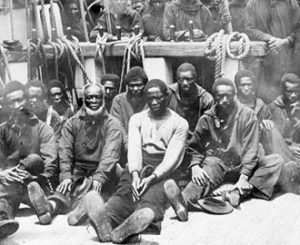

But by September 1861, naval vessels of the blockade, along the coasts, and later up the Mississippi were inundated with fugitive slaves, many wishing to enlist.

Commanding officers desperate for recruits pleaded with Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles for authorization to take them. Despite the ambiguity of the contraband’s legal status and the secretary’s questionable authority to act, Welles permitted enlistment of former slaves whose “services can be useful.”

Recruitment of contrabands (and freedmen) was carried out quietly, out of public view, and with much less controversy than would arise concerning the army. The most recent research has identified by name nearly eighteen thousand men of African descent (and eleven women) who served in the U.S. Navy during the Civil War. From spring 1861 through fall 1864, the percentage of African-American sailors increased steadily from less than 5 percent to a peak of 23 percent—a significant segment of manpower and nearly double the proportion serving in the army.[5]

Contrabands made up a considerable majority of those sailors; nearly three men born into slavery served for every man born free. By fall 1865, most wartime volunteers had been discharged, but African Americans still constituted 15 percent of the enlisted force, more than three times the percentage in service at the beginning of the war.[6]

Even without formal policies, persons of African descent were broadly associated with menial labor and personal service. Class and racial prejudices could informally segregate them and constrain their opportunities afloat. But such practices varied widely, influenced by location, type of vessel, and the personalities of officers and ship’s company.

Ships assigned to stores and supply duties, in contrast to warships, were disproportionally manned by African Americans. Ocean-going warships had relatively few, perhaps 5 to 10 percent.

Ships assigned to stores and supply duties, in contrast to warships, were disproportionally manned by African Americans. Ocean-going warships had relatively few, perhaps 5 to 10 percent.

Blockading vessels along the Atlantic coast drew many more, and on the Gulf coast not so many, while ships of the Mississippi Squadron relied mostly on them.

Freedmen from Northern states or other countries were more likely to gain sometimes grudging respect of officers and shipmates, particularly if experienced in the profession of the sea. They spoke and acted in more culturally comfortable ways; they were more likely to be accepted as equals and advance a few rungs up the enlisted ladder.

Those from northeast port cities might have commercial maritime experience, perhaps on the burgeoning steam packet service to Europe as cooks, stewards, deckhands, firemen, or engineers. Young men from towns and villages of New England often had two- to three-year whaling voyages under their belts. Along the shores of Chesapeake and Delaware Bays and Long Island Sound, they were familiar with small craft used in oystering, crabbing, and fishing. Many others stoked the furnaces and tended the boilers of river steamers.

Former slaves, however, continued to be stigmatized by a supposition of inferiority, were more stringently segregated among the crews, routinely assigned manual labor and busy work, and rated and paid at the lowest levels. Contrabands also provided valuable labor at shore installations.

The Confederate ironclad CSS Virginia exchanged broadsides with the steam frigate USS Minnesota in Hampton Roads on April 8, 1862. Minnesota’s aft pivot gun, manned by an African-American crew, was hotly engaged and two men were wounded.

“The Negroes fought energetically and bravely—none more so,” wrote their commanding officer. “They evidently felt that they were thus working out the deliverance of their race.”[7]

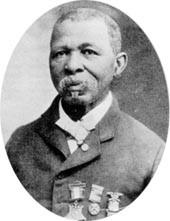

As in previous conflicts, African Americans of the Civil War navy proved their valor in many hard-fought clashes. John H. Lawson, Landsman, USS Hartford, won the Medal of Honor for heroism during the Battle of Mobile Bay. African-American sailors received 8 of the 307 Medals of Honor issued by the navy during the war.

[1] Steven J. Ramold, Slaves, Sailors, Citizens: African Americans in the Union Navy (DeKalb: Southern Illinois University Press, 2002), 15.

[2] Ibid., 16.

[3] Ibid., 21.

[4] Joseph P. Reidy, “Black Men in Navy Blue during the Civil War,” Prologue Magazine 33, no. 3 (fall 2001), https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2001/fall/black-sailors-1.html, accessed February, 2018.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ramold, Slaves, Sailors, Citizens, 122.

I find this subject fascinating. Nowhere near enough work has been done on the Civil War navies, much less work on the men who peopled those navies. Huzzah! . . . and thanks for the sources. I am glad we have decided to add our sourcework to the blog, and I suspect amazonsmile is glad as well. Again, thanks.

I am one of those who has learned little about the Civil War Navy, let alone sailors of African descent in the Civil War Navy. I learned a lot from your article. I was surprised by the fact that, at one point during the war, nearly one quarter of Navy personnel were Black. Thanks for bringing that and other facts about Union sailors of African descent to light.