A Conversation with Emma Murphy (part two)

(part two of five)

As we continue our Women’s History Month commemoration, we’re talking his week with Emma Murphy, a park guide at Andrew Johnson National Historic Site. Prior to landing her full-time permanent position there, she’d been working most recently as a seasonal ranger at Gettysburg National Military Park. Yesterday, she explained a bit about the complexities of getting a full-time permanent position with the Park Service.

————

Chris Mackowski: You mentioned to me the other day that there were a number of other people at Gettysburg, where you’d previously been stationed, that were in the system and waiting for a position to open up, and you had equated the situation to loving your troops enough but then having to send them into combat, because a supervisor ultimately has to make some hard choice about which one of those people to hire if a position does open up. What do you think about all those folks that are like airplanes circling the airport, waiting for their chance to land?

Emma Murphy: I think that’s very risky. I fully admit that you can fall in love with the park and want to stay there because you love it so much, and your goal is to be there for the rest of your career—but that’s not how the Park Service is designed. It was for a little while, where families could stay there and settle, but we’re starting to see a shift. There are a lot of people who want to move up in the Park Service, but you have to be willing to move and be willing to sacrifice your time to come circle back. It’s almost like the plane landing: to get there, your goal might have to change along the way.

That’s something I’ve noticed with people who are very successful in the Park Service and move up: they have a goal in mind, but they don’t necessarily have a location in mind of where that goal will be. There’s a piece of advice that I got when I was trying to get in to the Park Service, and that was to not settle for a Civil War park, because landing at one is almost impossible. Everybody wants to work at a battlefield, and I don’t blame them because it’s one of the most fun things to do—which sounds terrible because there was so much bloodshed—but the effect you have on visitors is almost intoxicating and thrilling at the same time.

As Ernie Price at Appomattox told me one time, it almost becomes an addiction where you have to get your NPS fix, and no matter how much you try to step back, that nag is constantly there.

So all of the NPSers that are out there with me—I don’t want to say I feel bad for them, because I understand and don’t pity them for wanting to stay at a spot, but I also feel bad about the fact that they may be worried or scared to be adventurous and get out and try something new. And if you don’t have the means to be able to pick up and move across the country to another state, you may be stuck in this vicious cycle that the park has, and it can turn into years and years and years of waiting. I’ve seen a lot of people that have had their mental and physical health deteriorate because of that, and I didn’t want to do that. It does make me feel terrible to watch people physically and mentally and emotionally deteriorate. It’s something that shouldn’t happen, but it’s a reality that some people face when you’re unable to breach the wall of permanent position. It’s almost like a taboo to say that you want to be a permanent, but that small chance of getting in is enough for some people to keep going until someone finally asks themselves, “When is enough enough?”

My answer was, after three seasons at Gettysburg, I had to find somewhere that had a position open—I had to be willing to leave. A lot of that had to do with my contract, because my contract didn’t allow me to up and leave and become a permanent; I had to work the system and get in through the Pathways system. Had that not happened, I don’t know if I could’ve financially and emotionally kept going through season after season as a regular seasonal because of the qualifications: you have to beat veteran preference, and you have to try and push through different qualifications at each regional level.

So in 2017, that reality became a purpose: to find the answer within myself as to whether I wanted to just work for Gettysburg or for the Park Service—and it was the Park Service. So, knowing that at the regional level I wouldn’t get a regular seasonal position, I had to find another way in. It’s unfortunate that the question you have to ask yourself is “When is enough enough?”

CM: You said you’re now basically doing what you’ve always wanted to do. What is your Civil War origin story? How did you fall in love with the Civil War and decide that this is what you wanted to do with your life?

EM: That’s a funny story because everyone always assumes it was my fiancée or my dad, but it was actually my mom that got me into it. She wanted to be a Civil War reenactor.

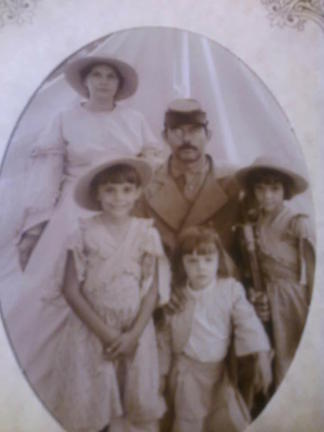

We were from Illinois in south Chicago, and there’s not much Civil War stuff out there. You have Lincoln and you have a little Grant, and that’s it for out in the middle of nowhere in a cornfield. My mom wanted to Civil War reenact, and by the time she started, she’d made her own clothes and she’d started the hobby with my dad. After her second or third reenactment, she was obviously pregnant with twins: myself and my sister, Rachel.

So, growing up, being engulfed in the Civil War was normal. It was something that was just normal on a Saturday after soccer practice, and it became part of my life as something that I didn’t even think about—until a family movie night when I was about eleven years old. My mom was going through the tapes of movies she wanted us to watch, and she found one, and when she put it in the VHS slot, it was a recording of Starman and Glory. They accidentally cut off the beginning of Glory, so I didn’t get to see the start of it, but when we played it, I was so upset and disturbed at the end because basically everyone dies. I was just appalled and wondered how it could happen. They had been so dedicated and worked so hard, and it was ridiculous, and I never wanted to watch that movie again.

That didn’t last very long. It turned into this huge obsession with the 54th Massachusetts and Robert Shaw. I was in love with him and the unit and the movie. I was so obsessed; it wasn’t a normal thing for a 6th grader to be liking. I tried to buy the movie at Wal-Mart when I was 11 and couldn’t do it because it was rated R—they wouldn’t let me buy it, so my father had to take my $20 that I got for my allowance and purchase my copy of Glory and hand it to me.

It turned into an obsession there, but where it became a part of who I am is something that I’m very proud of: I don’t stop. I fight like hell, which is kind of the theme of Glory. In 6th grade, we had a research project, and I wanted to do it on the 54th Massachusetts, and it was pretty much a paper on Glory because I basically regurgitated what happened in the movie, and I made a poster that had all the pictures of stills from the movie and actual pictures of the unit, and Robert Gould Shaw, and I made it into the collage. I was horribly bullied and called a freak because “the Civil War is over and it’s not that cool and nobody likes that.” They used to shove my books off of my desk because I carried around the letters from Robert G. Shaw—that was my everyday reading for reading time.

So, anyways, I had to put the poster on the windowsill because it was too big, but coming back from recess, I found my poster completely crumpled and stomped on and in pieces. Everybody was like, “Oh no, it looks like you can’t do it. I guess you have to pick another normal topic.” So I stood there and had a moment where I had to either admit defeat or fight like hell. So I took it home—and I didn’t realize that laminating was an actual machine; I thought teachers just put packing tape on something until it became a solid sheet of plastic—so I taped my poster up with clear packing tape, and it was crumpled so you couldn’t really see it, but it was clear as day for me and, damn it, I still went up at the end of the year and gave my presentation and everybody was silent because I did it. That was kind of the moment where I realized this was going to be a lifelong thing.

But that was in 6th grade, and obviously there is a lot of time left before you decide what you want to do with your life, so I didn’t realize that this could be a part of an education and part of my own research and my career until I was about to go off for college. Originally, I was going to be a professional French horn player in the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. The Chicago Youth Symphony Orchestra was looking into having me audition and be one of their French horn players before going into the official CSO, but I had two facial surgeries in high school, and the last one had my mouth wired shut for nine months, so I figured it probably wasn’t a good idea to put my entire career on my facial muscles when they didn’t really work properly—and it was just a birth defect that I had to work with, everything’s fine now and has been since then, about 8 years ago, but I panicked. I was a junior in high school—I was 17—and I didn’t know what to do.

I will give full credit to Pete on this one that—thank God he did this—when I walked into my first internship interview in 2011, I was very nervous, although I thought it went really well. But because I was the younger of two freshmen to apply, the Park Service representative said he wanted the other student—but she wanted to go to a specific spot, not necessarily the one she was going to be offered—so he didn’t know who he should pick. Pete flat-out said that he should pick me. Coming straight out of that person’s mouth after the 150th of Fredericksburg event, he said the best decision he made in 2012 was to hire me as one of the interns even though he originally hadn’t want to. I appeared too young and didn’t have any experience, but Pete had told him he was making one of the biggest mistakes if he didn’t pick me. Even now, 6 years later, anytime I talk to him, he says, “So are you still talking really fast or have you learned to slow down?” [laughs]

So that’s basically my Civil War lifestyle all the way up to my Civil War career. It was a long road, but it was really worth it and really fun.

———–

In tomorrow’s segment of the interview, Emma will talk about finding her way at her new park and what she’s discovering about Andrew Johnson.

I fondly remember the all Murphy women at reenacments and seeing the twins grow into young ladies. Congratulations !