Annie Brown: The Forgotten Conspirator

In my Civil War class, I have students read Tony Horwitz’s book, Midnight Rising: John Brown and the Raid that Sparked the Civil War, to learn about John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry. Many Civil War readers know Horwitz best from his initial foray into the genre with Confederates in the Attic. In my opinion though, Midnight Rising is even more compelling. My students spend four weeks discussing its contents and finish by writing a paper to answer the question “Did John Brown fail?”. There is never a dull moment in either conversation or written word when it comes to this topic.

In my Civil War class, I have students read Tony Horwitz’s book, Midnight Rising: John Brown and the Raid that Sparked the Civil War, to learn about John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry. Many Civil War readers know Horwitz best from his initial foray into the genre with Confederates in the Attic. In my opinion though, Midnight Rising is even more compelling. My students spend four weeks discussing its contents and finish by writing a paper to answer the question “Did John Brown fail?”. There is never a dull moment in either conversation or written word when it comes to this topic.

However, one aspect of the John Brown story that is often overlooked is his daughter Annie’s participation in the raid. When John Brown set up camp at the Kennedy Farm in Maryland, just five miles from Harpers Ferry, for organization and reconnaissance work during the summer before the raid, Annie and Brown’s daughter-in-law Martha joined him there as part of his cover story. The two women arrived on July 19, 1859 and stayed just over two months until September 29.

I decided to explore Annie’s role in the whole affair in a presentation for International Women’s Day on March 8, 2018, at a day-long symposium offered at Capital University in Columbus, Ohio. My research extended beyond Horwitz’s insights and confirmed my perception of Annie as a bold and courageous young woman who contributed to both her father’s raid and to the construction of his memory.

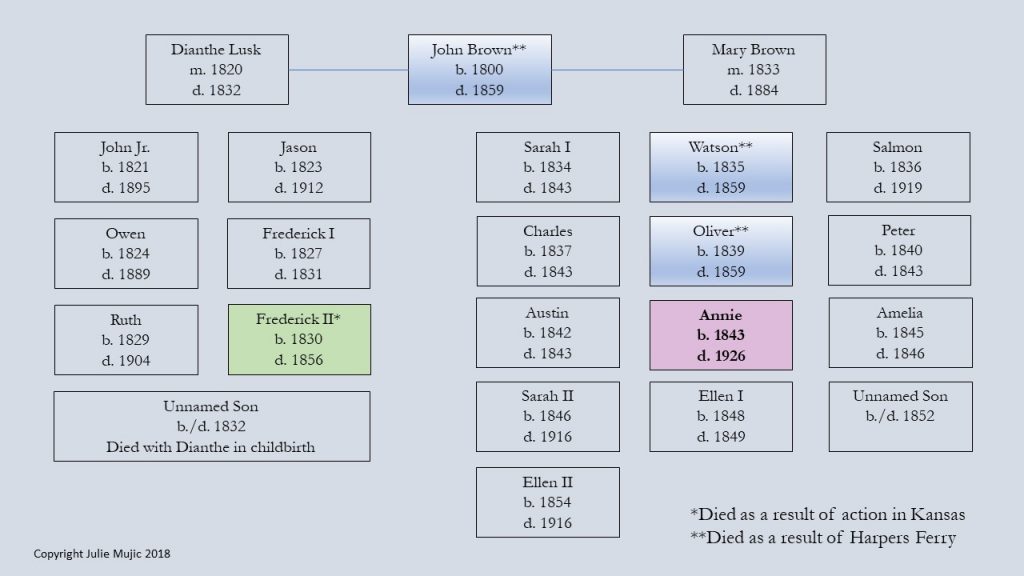

Annie Brown was John Brown’s fifteenth child, born to his second wife, Mary, in 1843.

In the summer of 1859, she was 15 years old and had been raised in a deeply religious household that centered on her father’s determination to bring about an end to slavery. When Annie arrived at the Kennedy Farm in July 1859, she was excited to assist Brown in his plans, which she had heard about for years. She and Martha went to work cooking, cleaning, making bedding, and doing laundry. But, her most important role was that of lookout. She watched for nosy neighbors and intercepted them so they would not discover the growing number of men arriving at the home. She called Brown’s raiders her “invisibles” and became devoted to them.

The days were very long, but she spent time watching the men plan, drill, and debate a wide range of topics. Annie heard, and sometimes participated in, heated conversations about slavery and religion; revelations about both topics caused fundamental shifts in her perspective and she never held her father’s religious views again after this experience. Indeed, she even questioned her part in Brown’s plan for Harpers Ferry:

“It was sometimes a hard matter for me to reconcile myself to the fact that the father who had always before this taught me to speak the truth should place me in a position where I was obliged to constantly tell lies, go by a false name, and live a false life… I used to wonder if God would bless a work that had to be done that way.”

These doubts did little to detract from her enthusiasm for the cause and she and Martha returned home on September 29, 1859, anxious to hear of her father’s success. Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry commenced on October 16. The incursion lasted less than two days, and Brown and six of his men were arrested, ten men died during the raid, and five men escaped. Oliver and Watson Brown, two of Annie’s brothers, were among those killed. Brown was tried, convicted, and hanged in December 1859.

Annie was despondent over news of the raid’s failure. Her sister, Ruth, later recalled,

“Annie’s grief was terrible to see. She had known every man who fell in the fight, had been present at all their conferences, and was like a sister to many of them…She went about the house pale, silent, and tearless. She neither slept nor ate, and I feared for her reason”

Annie wrote, just two days after Brown’s execution, “For my part I feel proud when I think that his blood runs in my veins.” She never wavered in that sense of dedication to her father and she also defended the other men for the rest of her life.

During the Civil War, Annie despaired that she could not fight as a soldier. She went into Virginia and taught freed slaves in schools set up by Union officials but in 1864 she moved to California with her mother and siblings to seek a new life and economic opportunity. They all needed a break from the constant scrutiny of being John Brown’s family.

Annie’s postwar life was difficult. She married an older man with a penchant for alcohol and she and her children suffered abuse for many years. They were never financially stable. Despite these obstacles, Annie remained focused on controlling the narrative about her father. In the years following the Civil War, Annie kept a close eye on the books written about both John Brown and the raid on Harpers Ferry. She spoke stridently against interpretations that presented him as crazy or dangerous and she often wrote for newspapers to critique new publications.

One of Annie’s biggest points of frustration was how little credit she received for her role. In the roundup after the raid, as her brothers at home feared arrest for conspiracy, no one ventured to ask whether she should also be held responsible for her role, which she found insulting. It also took constant demands on her part for people to believe that she had perspectives that were worth listening to – that her knowledge of the raiders and of her father’s purpose could shed light onto the mission and its meaning. As late as 1894, she remarked, “It always seemed a little queer to me that so many persons have attempted to publish books or articles on John Brown without consulting me just a little.”

Annie died in 1926, having suffered from poverty most of her life. Her legacy is complicated by statements she made later in life that adhered to Jim Crow notions of race, especially her vocal criticisms of the black community for not being grateful enough to her father for his actions on their behalf. I highly recommend the book The Tie That Bound Us: The Women of John Brown’s Family and the Legacy of Radical Abolitionism by Bonnie Laughlin-Schultz for more insight into how Brown’s remaining children shaped, avoided, and lived with his memory. Annie was a part of that story, actively espousing a narrative of heroism on the part of her father and his “invisibles” until the day she died. While she did not tote a gun into Harpers Ferry on that fateful October night, her actions at the Kennedy Farm that summer helped disguise her father’s true intentions and thus contributed to his ability to execute an event that shook the country to its very core. Annie Brown never apologized for her support of the raid, both at the time and in later years. She was a critical part of the story and wanted to be remembered that way.

Julie Mujic is a Scholar-in-Residence at Capital University and owner of Paramount Historical Consulting, LLC. She also serves on the Board of Trustees for the Columbus Historical Society and the Westerville Public Library. Feel free to contact Julie through www.juliemujic.com.

All quotes can be found in Bonnie Laughlin-Schultz, The Tie That Bound Us: The Women of John Brown’s Family and The Legacy of Radical Abolitionism (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2013), pages 59, 66, 67, and 147.

“Shook the country to its very core…” is putting it mildly. What I still find both amazing and appalling is the cloak of romanticism that still enfolds this demented fanatic, and zealots like Yancey and Rhett in the South. 750,000 dead, untold thousands crippled, the complex infrastructure, both physical and financial of an entire region decimated, racial issues unresolved, and Annie Brown was “frustrated” that she didn’t get more credit? John Brown couldn’t be satisfied with the butchery of Pottawatomie; by working to defeat all possibilities of gradualism or rational democratic process, he deserves the rich condemnation of history. As do the reactionaries of the South.

“possibilities of gradualism or rational democratic process”

LOL. A couple hundred years of American slavery wasn’t enough for you I guess.

“ the complex infrastructure, both physical and financial of an entire region decimated”

LMAO. Did you whine about the destruction of Nazi Germany too ?

You lost. Now stfu and go on to hell

Congratulations, this is the new worst thing I’ve ever read on the internet.

John Brown is one of the greatest heroes in human history.

I would love to be a fly on the wall in your class Miss Julie during those four weeks. Watching students grapple with such a complex issue involving so many hot button factors and come to there own decision is one of the joys of life. Great contribution ANY month of the year, not just Women’s History month. Yet another great hire by ECW. I look forword to more outstanding and informative articles Miss Julie, hey your the one who keeps setting the bar so high ?????/5 Red apples!!! (95% of the litirature I consume speaks of John and his son, no mention at all of the ladies)

My bad, did not spend enough time on your bio. Dr. Julie it is forthwith

Your report on Annie Brown was so very interesting, since I had never read of any reference to her or her remaining family. I live in Columbus, OH, and would appreciate receiving any notices of future classes or talks that you would offering in the area. My husband and I attend as many of the Central Ohio Civil War Roundtable as we are able. Are you on their speaker list?

The despicable comments made by John Pryor, above, go far towards illustrating the nature of the ongoing battle for the very soul of America which presently divides the country. On the one hand are the revisionists and apologists who would be just fine with Plutocracy and Fascism, and on the other are those who have learnt the Lessons Of History, and are determined not to repeat them. Kudos for ‘Ted’ in his reply: you ought to give Talks, sir. :o) As for Mr. Pryor and his ilk, I have the following words for you: ‘America: Change It Or Lose It.’

I read and enjoyed Horowitz’ book years ago, and appreciate the opportunity to become reacquainted with Annie.

Sorry for the length of this, but it can’t be helped. This is a very interesting piece. I am no expert on John Brown but he is most certainly one of American history’s most compelling characters. But one fact remains: he is never viewed in a neutral context. He is either the most despicable of villains, or he is perceived as a most revered hero. Or so it seems. Frederick Douglass, among others, lauded him as a hero and a visionary. Others scorn him then and now as a murderous demagogue with something akin to a ‘Messiah Complex’. I doubt that any future judgements of him will arrive at a universal determination of just what he was, or remains.

That said, I find his daughter Annie to be quite interesting, to say the least. This article portrays her as somewhat ‘whiny’, in that she believed she never got credit for what she did in her father’s camp pre-raid and in her being ignored as a source for information about her father. Perhaps the financial difficulties she had in her adult life contributed to her frustrations, in that her info might have been a hoped-for source of income? Regardless, she was obviously bothered by it all.

But did she have a point? It is reasonable to conclude that she could have provided quite a few insights about her father’s insights, motivations, ambitions, character, etc. Did she have valid reasons for feeling the frustration she did? I personally do not know, but the question stands.

The comments on this thread covered a fairly wide range of things. ‘Nazis’ were mentioned, and I will get to that in a moment. There is a term that is often bandied about that says “The end justifies the means”. No one can argue that the elimination of a long established evil like slavery was, and remains, a great thing. So do the end results of what John Brown contributed to justify any of the means taken to achieve them, especially by him? In wartime, the winning side not only gets the spoils, but they usually get to write the narrative. I mentioned ‘Nazis’ at the beginning of this paragraph. The ‘means’ taken to destroy them resulted in the deaths and maimings of countless innocents, both in their home country and in the countries they occupied. The same can be said of Japan. Nazi and Japanese leaders were tried for war crimes. In that context, the Allies employed mass firebombing raids on entire cities in both countries. Had the Nazis/Japanese prevailed, and the Allies homelands conquered by them, there no doubt would have been Allied leaders facing public war crime proceedings. As it was, the great evils that both regimes represented were vanquished, thus, those means are usually excused.

Does any of that apply to John Brown? Should he receive any CREDIT for how things turned out? Should blacks in the USA today view him as Frederick Douglass did? In THAT regard, I find this statement from the author of this article somewhat at odds: “Her legacy is complicated by statements she made later in life that adhered to Jim Crow notions of race, especially her vocal criticisms of the black community for not being grateful enough to her father for his actions on their behalf.”

I don’t find how that compares with ‘Jim Crow’ at all. Does she have a point that blacks then in that later part of her life, and I will add blacks today, owe her father any real gratitude? I think THAT is a fair question to discuss

sorry for my poor english, I’m french and John Brown has always fascinated me, and it was a pleasure to discover a little more about his daughter

Thanks so much for posting this. I live near Harpers ferry and have been trying to become more knowledgeable about the historical aspects of it. And one of the exhibits of John Brown’s museum there is a very short mention of Annie and I was very curious about her and was just about to go the long route of searching indexes of books for references. I plan on checking to see if the book you mentioned is in my library. Thanks again!

I want to recommend a book to all of you. The title is fire on the mountain and the author is Terry Bisson. It’s a what if novel where John Brown’s raid succeeds and ignites a revolution by Black people. I love this book

My grandmother Alice Adams was Annie Brown Adams grand daughter. They lived in Humboldt County. Grandma Alice remembered Annie as very stern. At one time, Annie possessed a good amount of her father’s writings and correspondence. But my grandmother recalled Annie burning them. She didn’t want any of John Browns personal letters to be open to anyone getting them. My family did have clippings and old photos, and a very small type of journal that belonged to Annie. There were only about 8 pages with writing. As a child I loved reading it over and over.