Bittersweet Appomattox

First Lieutenant Robert Pratt belonged to the 5th Vermont Infantry, a regiment that rightfully claimed credit as the first unit to irreparably break the Confederate lines southwest of Petersburg on April 2, 1865. Pratt played a pivotal role in the Union assault that morning and survived to tell the story of the battle that forced the Confederate evacuation of Richmond and their surrender a week later. The day after Appomattox, Pratt reflected on the Petersburg breakthrough. He looked forward to the bright future ahead of him but had lost several close friends during the decisive combat. The nineteen year old officer attempted to sort these feelings out in his diary entry of April 10, 1865.

“We know now that the war is ended and how it thrills me with joy to know that we have accomplished what we have fought [four] years for. I can hardly get through my head that we can go on picket and not keep a vigilant look out for rebels. All I want now is an education and I am bound to have one. We think the fighting is done and that the day is not far distant when we will start for home. We often think of Ed Brownlee and Charlie Ford. How hard it seems that they should get killed in the last fight.”

Both fallen soldiers belonged to Captain Charles Gould’s Company H of the 5th Vermont Infantry. Sergeant Edward Brownlee, a native of Montreal, was killed on the parapet during the charge on April 2nd. Lieutenant Colonel Ronald A. Kennedy, commanding the 5th Vermont, wrote Brownlee fell “in the thickest of the strife while cheering on the men of [Company H].” Though Pratt was just yards away at the time, the lieutenant did not learn that his friend was killed until that night.

Two of Corporal Charlie Ford’s brothers had already been killed during the war–one at Mine Run, the other at Spotsylvania. The twenty-two year old was among the first to reach the Confederate lines and was cut down by a bullet while cheering, “Come on boys, the works are ours!” Both Brownlee and Ford were buried on the battlefield and later reinterred at Poplar Grove National Cemetery, today a unit of Petersburg National Battlefield.

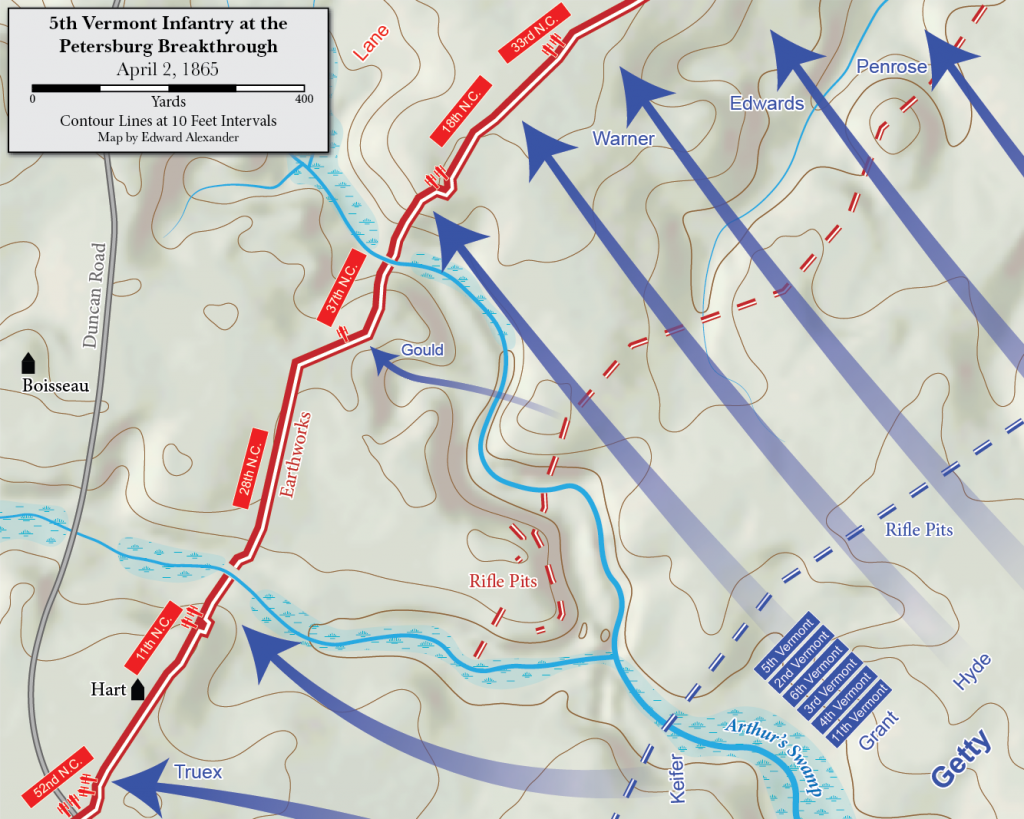

Lieutenant Pratt also acted gallantly that morning. Kennedy wrote that Pratt “added materially to his reputation of being a soldier in every sense of the word, as well as one of the most unequaled daring.” The lieutenant charged forward armed with his officers’ sword. When just a few hundred yards away from their target, Captain Gould shouted orders to “Bear to the left.” Pratt guided about fifty men into a defilade where they took cover from Confederate fire and reported the unit’s strength to the captain. Gould deemed it a sufficient number. The captain wanted to press forward immediately, fearing fire from both directions if they lingered in between the Confederate works and the next wave of Union attackers.

Gould swiftly led the way to the imposing earthen wall, outpacing the rest Company H as he rushed through a gap in the tangled abatis and into the fortifications. The young captain received credit as the first soldier to scale the Confederate earthworks but suffered severely for that distinction. North Carolina infantrymen bayoneted him in the back and jaw, struck him on the head with the flat of a saber, and battered his body with their clubbed muskets. Gould battled back as best he could until Corporal Henry Recor pulled him back into the safety of the ditch.

Pratt meanwhile formed the rest of the company to attempt the desperate struggle up to the parapet. He did not see Gould enter the earthworks but soon received word that the captain was dead. Though Gould survived his wounds, he was in bad shape and stumbled back to the Union lines to seek reinforcements and medical care. For the rest of the day, Pratt would lead Company H. The lieutenant stated they entered the Confederate earthworks at 5:04 a.m., twenty-four minutes after the boom of a cannon from Fort Fisher signaled the beginning of the Union assault.

A Confederate artillery piece was poised just to the left of Pratt’s entry point and threatened to fire a devastating volley into the waves behind the 5th Vermont. Pratt rushed to the cannon and swung his sword toward the gunner before the Confederate could fire. The cannoneer dropped his lanyard and dove for safety underneath the gun carriage. Pratt sent him to the rear as a prisoner before leading his company further down the line.

Afterward, Captain Gould was properly recognized as the first to breach the earthworks and later received the Medal of Honor for that action. While responding to one inquiry about that decisive morning, Gould wrote: “It was reported to Lieutenant Pratt that I had been killed inside the works. Forming the men in the ditch, he led them into the work, and, after a short but desperate fight, captured the guns and a number of prisoners, and held the works until other troops arrived; but in the excitement of the battle and his anxiety to rejoin his command, Lieutenant Pratt left his guns and prisoners to the first comers, and, omitting to place guards upon or take receipts for his captures, did not receive the credit to which he was entitled.”

Glory could wait that morning. Bigger prizes lay ahead. By the end of the day the Vermonters had swept four miles of the Confederate line south to Hatcher’s Run and turned north to attack the artillery defending Robert E. Lee’s headquarters on Petersburg’s western outskirts. They settled in for the night around the smoldering ruins of the former Confederate headquarters at Edge Hill. “We were completely tired out,” Pratt wrote that night in his diary. There he learned of Sergeant Brownlee’s death and “went to sleep a crying.”

Detailed to the skirmish line the next morning, Pratt briefly entered Petersburg before joining in the race westward that led to Appomattox. The VI Corps fought again at Sailor’s Creek on April 6th but the Vermonters were not engaged. Assigned a rear place in Ulysses S. Grant’s mobile pursuit column, they had only reached Farmville by the time of Lee’s surrender.

On April 9th, Pratt was detailed to guard the town. He posted pickets along Main Street and in a church near the Ladies College. “All very quiet,” he wrote. Rumors trickled in of Lee’s surrender but Pratt’s attention was briefly drawn elsewhere. “We have to start and look at the Misses sitting in the window of the seminary. There is so many of them and they have the name of being so much secesh and we are so timid we do nothing but gaze. If I were not afraid of a flogging would go and tell them that Lee had surrendered.”

Official word of the surrender arrived the next day. Pratt collected his thoughts on his friends’ sacrifice and wrote his poignant diary entry. He remained in the army until mustering out as a captain on June 29, 1865. Immediately he sought to make up for the teenage years he had lost while in the army.

Four summers earlier he had joined the 5th Vermont as a fifteen year old on break from his studies at Brandon Seminary. The son of a modest laborer on a small farm, Pratt had attended public school and worked on his own to earn money to attend the seminary. He valued education, evidenced in his diary entry on April 10, 1865, and resumed studying upon his return to Vermont. Robert graduated the following year. His brother Sidney also served with the 5th Vermont until receiving a serious wound at the Wilderness. A doctor advised that Sidney move west after the war for health reasons and Robert joined him in relocating to Minnesota in November 1866.

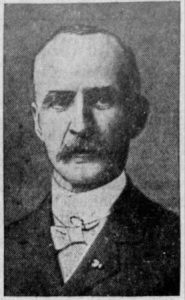

Settling around Minneapolis, Robert worked at a lumber yard and eventually managed his own lumber hauling team. A bright entrepreneur, he eventually bought his own land to timber and managed a lucrative business. He married Irene Lamoreau on August 30, 1871, and the couple had seven children.

Pratt became involved in politics and served on the Minneapolis city council from 1884 to 1887 and was elected to the school board in 1888. Seven years later he was elected Minneapolis mayor and was reelected after two years to a second term. An admirer wrote, “It is doubtful if Minneapolis ever had a more popular and efficient chief executive.” Pratt died on August 8, 1908 and was buried in Lakewood Cemetery. In a resolution passed to honor their former colleague, the city council noted:

“As a citizen and official Mr. Pratt always evidenced great interest in educational matters, and it may truly be said that his greatest public service has been on the Board of Education… Mr. Pratt was a man of pure mind and he lived a clean and useful life. His long and useful service in this community has indelibly impressed itself upon the history of this city.”

Pratt fulfilled the life he dreamed of the day after Appomattox. Tragically, two of his close friends would not enjoy the same. Lee’s lines had been stretched to their limit by April 2, 1865, but breaking both them and the Confederate commander’s will to fight required sacrifice until the very end.

We read so often of veterans whose lives were tragic after the war ended, and this is dreadful. Nevertheless, we must remember that most veterans went from the army forward to live useful, productive lives.They positioned America to roar into the 20th century ahead of many other countries in many ways. Life is never easy, but American vets continue to give, even after they take off the uniform. This gentleman is a good example. Thank you.

Thanks for this compelling story, and for following the thread of Robert Pratt’s like through his post war years. I agree with Meg’s comments on their impact on America. The post civil war “Guilded Age” is often remembered mainly for its corruption and robber barons, but the fact is it was a time of America’s advancement in many areas. And Civil War vets– just like the veteran “Greatest Generation” of the WWII era– were among its greatest leaders.

Pratt is my great great grandfather and it was very interesting to learn more about him thank you for putting this together.

I would like to have a bronze military marker from the U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs installed at the gravesite of Robert Pratt. There is a large Pratt family stone at the gravesite and a very small flat marker that simply says Robert Pratt, 1845-1908. It says nothing about his military service. However, Lakewood Cemetery in Minneapolis only allows one marker per person. The small marker would have to be removed and the VA marker installed in its place. I cannot request this because I am not a relative or descendant of Robert Pratt, but I am a Civil War historian. I would need permission in writing from a living descendant of Mr. Pratt. The markers are free from the VA and Lakewood Cemetery would install it. Please contact me about this project. Thanks. Gary Nelson in Minnesota.

I have his 6th Corps badge from the Wilderness

I discovered this article by accident this morning. I am also a descendent of Pratt. I enjoyed the story. I see that his mindset has been shared and passed down to his family. Some of his characteristics are continued to be taught to his extended family today. God Bless!

I would like to have a bronze military marker from the U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs installed at the gravesite of Robert Pratt. There is a large Pratt family stone at the gravesite and a very small flat marker that simply says Robert Pratt, 1845-1908. It says nothing about his military service. However, Lakewood Cemetery in Minneapolis only allows one marker per person. The small marker would have to be removed and the VA marker installed in its place. I cannot request this because I am not a relative or descendant of Robert Pratt, but I am a Civil War historian. I would need permission in writing from a living descendant of Mr. Pratt. The markers are free from the VA and Lakewood Cemetery would install it. Please contact me about this project. Thanks. Gary Nelson in Minnesota.