Unvexed Waters: Mississippi River Squadron, Part I

History offers few examples other than the Civil War and Vietnam of extensive operations on inland shallow waters involving specialized classes of war vessels commanded and manned by naval personnel. The struggle for the Mississippi River, the spine of America, was one of the longest, most challenging and diverse campaign of the Civil War. The river extended 700 miles from Mound City, Illinois, to the Gulf of Mexico.

Strategically, the river war was an extension of blockade, an outgrowth of the Anaconda Plan. On June 10, 1862, Major General William T. Sherman wrote to his wife Ellen: “I think the Mississippi the great artery of America, whatever power holds it, holds the continent.”[1] But in technology and tactics, river warfare was an entirely new concept. Both navies started with nothing—no warships, no experience, no tactics, no command structure, no infrastructure.

Operations would involve: Joint and amphibious expeditions; reduction of powerful shore fortifications; interdiction of enemy trade, communications, and transportation; and river patrol and guerrilla suppression, all while sustaining and protecting friendly activities.

Technology would include ironclads, steam-powered gunboats, modern fortifications and artillery, and mines, all relatively untested instruments of war. The U.S. Navy, an exclusively deep-water force, had never thought very much about any of these challenges.

Under the watchful eyes of the commander in chief, Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton developed a close partnership, built a robust riverine force from nothing, and coordinated on strategy.

There was no joint staff, and no protocols or mechanisms for directing joint operations. The officers of one service, however senior, could issue no orders to an officer of the other service, however junior. Coordination at the operational level depended entirely on the willingness and abilities of field commanders to plan and execute together.

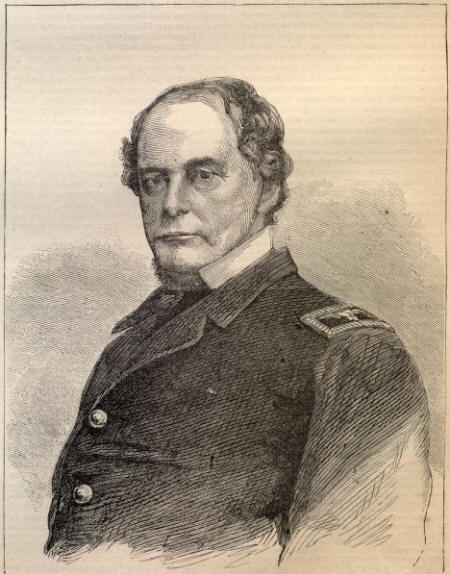

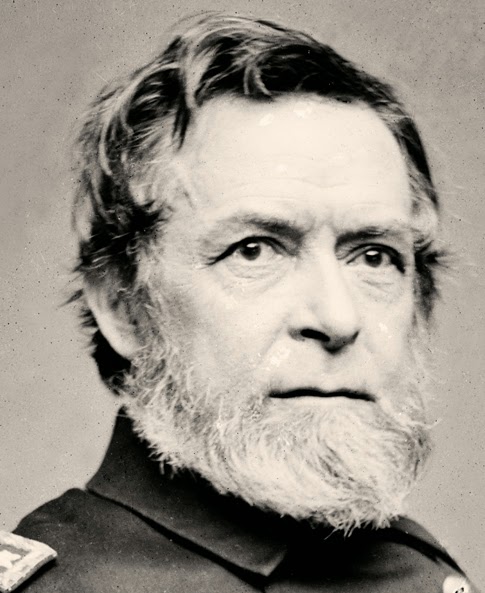

A lack of joint perspective impeded many operations and negated strategic opportunities, but Flag Officer Andrew H. Foote, Flag Officer H. Charles Davis, Admiral David D. Porter, and General U. S. Grant put differences aside. From his first battle to his last, Grant incorporated the navy as an integral combat and logistical arm, and he credited navy compatriots as a major factor in victory.

In May 1861, Secretary Welles appointed Commander John Rodgers to: Establish “a naval armament” on the Mississippi and Ohio rivers, blockade or interdict Rebel communications, and “aid, advise, and cooperate” with army commanders “in crossing or navigating the rivers or in arming and equipping the boats required.”[2]

This ad hoc fleet would become the Western Gunboat Flotilla, a unique “joint service” organization. Gunboats were manned by navy personnel, but were converted or built using funds from the War Department, and were under the command of the army.

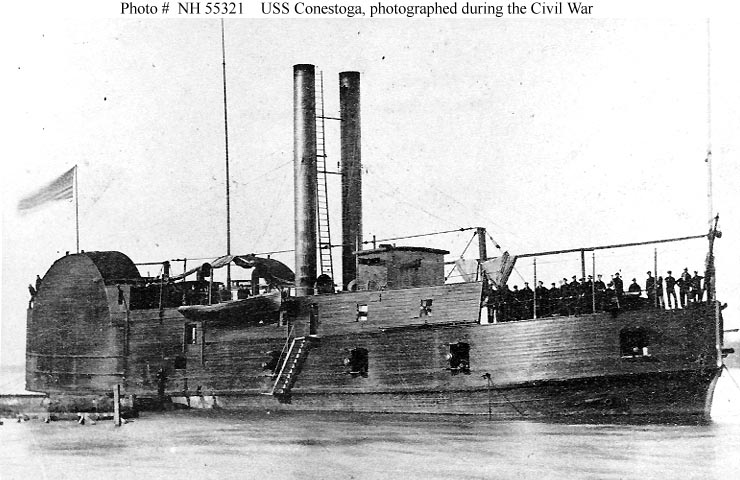

Working out of Cincinnati, Rodgers purchased three commercial steamers and contracted for their conversion. The USS Conestoga, USS Tyler, and USS Lexington were the first commissioned warships dedicated to river conflict.

Boilers and steam pipes were lowered into the hold; superstructures were removed and replaced with 5-inch thick oak bulwarks; sides were pierced and decks strengthened for six or eight guns.

Rogers acted entirely on his own initiative, without instructions, plans, authority, and initially without funding. He was rebuked by the Navy Department for so doing. These small but powerful vessels probably saw more service than any other gunboats in the Western Theater.

The next step was to design and build gunboats from the keel up, producing the first uniform river warship class and the first U.S. ironclads to enter combat.

Rogers partnered with James B. Eads, a wealthy St. Louis industrialist and self-taught naval engineer who risked his fortune to build the vessels. He was an exceptional river navigator and would become a world-renowned civil engineer and inventor.

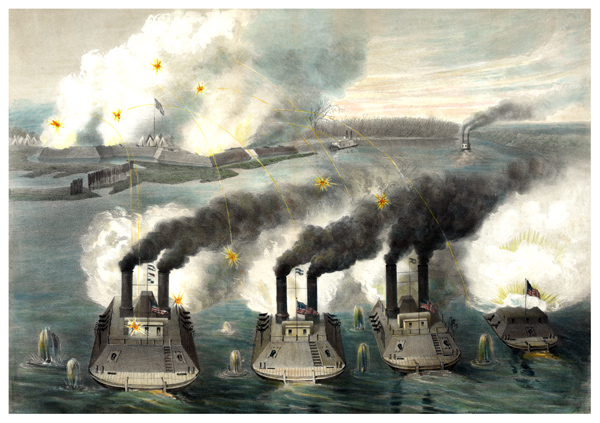

Noted naval architect Samuel Pook designed the ironclads, which were thereby dubbed “Pook Turtles.” They combined firepower, protection, and mobility in a manner achieved by few contemporaries, but with defects.

The armor was inadequate. Maneuverability was restricted. They had no watertight compartments to isolate damage. They were vulnerable to mines, which sank the USS Cairo and USS Baron De Kalb, and to ramming, which sank (if only briefly) the USS Cincinnati and USS Mound City.

These ironclads were the backbone of the river flotilla taking part in almost every significant action on the upper Mississippi and its tributaries.

Other ironclads included the USS Benton, a converted center-wheel catamaran snag boat (the largest and best vessel of the Western flotilla), and USS Essex, along with a few smaller and partly armored gun-boats.

Dozens of other flat-bottomed river steamers were purchased and converted into armed and armored warships to patrol, escort, transport, and communicate over hundreds of miles of rivers through occupied territory. Thin metal sheeting, usually tin, provided small arms protection, hence “Tinclads.” The luxurious USS Black Hawk became Admiral Porter’s command ship.

The United States Ram Fleet—later the Mississippi Marine Brigade—was an odd duck, a small volunteer navy commanded by a family with no military experience. It was the brainchild of noted civil engineer Charles Ellet, Jr. who was convinced that, with steam power, ramming again was a viable naval tactic.

In March 1862, he persuaded Secretary of War Stanton to appoint him a colonel of engineers with authority to build his own flotilla. Ellet converted several powerful river towboats, heavily reinforcing their hulls for ramming. Boilers, engines and upper works were lightly protected with wood and cotton. Originally not armed, they later were fitted with several guns.

Colonel Ellet reported directly to the Secretary of War, operating independently of the squadron and theater commanders. When Ellet received a mortal wound at the Battle of Memphis in June 1862, command passed to his younger brother, Alfred, and to his son, Colonel Charles R. Ellet. The rams figured prominently in actions around and below Vicksburg into 1863 and performed supporting roles for the remainder of the war.

Colonel Ellet reported directly to the Secretary of War, operating independently of the squadron and theater commanders. When Ellet received a mortal wound at the Battle of Memphis in June 1862, command passed to his younger brother, Alfred, and to his son, Colonel Charles R. Ellet. The rams figured prominently in actions around and below Vicksburg into 1863 and performed supporting roles for the remainder of the war.

In February 1862, Flag Officer Andrew Foote succeeded Rodgers as flotilla commander. He and Grant formed a potent army-navy team against Fort Henry on the Tennessee River and Fort Donelson on the Cumberland, blowing open the Confederacy’s heartland, exposing Nashville, Shiloh, and eventually Chattanooga along a wet highway into northern Mississippi and Alabama.

The main Rebel defense line in the west collapsed, abandoning all of Kentucky and most of middle Tennessee along with crucial economic resources such as iron and pork. These were perhaps the deadliest strategic strokes of the war as well as the greatest single supply disaster for the Confederacy.

Foote’s gunboats pounded the poorly sited and constructed Fort Henry into submission before Union troops even arrived.

Foote’s gunboats pounded the poorly sited and constructed Fort Henry into submission before Union troops even arrived.

At Fort Donelson his ironclads took considerable damage until “Unconditional Surrender” Grant surrounded and battered the Rebels into capitulation, bagging an entire Confederate field army and beginning Grant’s rise to supreme command.

Together they achieved a strategic outcome George McClellan would fail to obtain during the Peninsula Campaign that spring.

Part 2 will complete the story.

(Extracted from a paper presented at the North American Society for Oceanic History (NASOH) Annual Conference, St. Charles, Missouri, May 22, 2018. This presentation with PowerPoint is available for interested groups. See www.CivilWarNavyHistory.com.)

[1] Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman to Ellen Sherman, June 10, 1862, University of North Dakota, Sherman Family Papers.

[2] Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, vol. 22 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1894-1922), 280, 284-285.

Thank you for posting this I’ve just started reading a novel (The Narrow Fury) based around this campaign by an author called Donald A. Joy this will be very helpful in following all the various ships and characters.

Looks interesting. Good to see some Civil War navy fiction. I’m happy to shed some light on a fascinating subject.

I look forward to the next blog post, If Donald Joy’s in the afterword to his books is to be believed he is writing a longer series that will cover various aspects of the navies role in the Civil War.

I’ve read the first book ‘A Sudden Thunder’ which runs from December or 1860 until just after the Battle of Hampton Roads and I am looking forward to the third book whenever it appears.

Fantastic article, Dwight! Great research!

On the 21st of April 1862 a two-ship task force proceeded up the Tennessee River from Pittsburg Landing and completed a mission attempted twice before: destruction of the Confederate “fast transport” Dunbar. Discovered near Florence Alabama a short distance up Cypress Creek, the Dunbar was aground in shallow water; sailors from the U.S. gunboat Tyler set her ablaze and burned her to the waterline. In addition, a smaller sternwheel steamer of only 80 tons and drawing less than four feet was encountered in operation as transport by the Rebels on the Tennessee River below Muscle Shoals. The Alfred Robb was forced to surrender to the task force; soon she was armed, provided with “armor” around pilot house and quarterdeck, and crewed by “strong Union men” from Savannah Tennessee. At some stage, the Robb was given the additional identification Number 21. But she was the first Tinclad operated by Federal Forces on the Western Rivers.

The above details of Union tinclad Robb are provided in order to recognize the 160th Anniversary of the capture of that vessel; and to assert that “despite having identification No.1 the Rattler was not the first Tinclad (as claimed in other references.)”