Trial by Fire for the U.S. Sharpshooters at Yorktown, Part 1

Emerging Civil War welcomes back guest author Rob Wilson.

The men of the 1st Regiment, U.S. Sharpshooters (U.S.S.S.) were tired and hungry as they slogged along the muddy road from their base at Ft. Monroe. It was April 5, 1862, and they were leading a long Army of the Potomac III Corps column towards Yorktown. The soldiers had marched hard the previous day, bivouacked the night on wet ground, gulped down a cold breakfast, and started marching again. Now, adding to the misery, an intermittent rain soaked their uniforms.

Yet the physical discomforts of this march were not the Sharpshooters’ foremost concern. The men were in Southern Virginia and moving into Confederate-held territory. Yorktown lay just ahead, through the rain and mist, and the river port was well fortified. Enemy resistance was guaranteed. In addition, most in the 750-man regiment had never seen combat. These Sharpshooters faced the kinds of existential questions any soldier confronts before his first battle. How might I react? Can I measure up? Will I live through the day?

All questions were soon to be answered. An artillery shell from a previously unseen enemy battery whistled by and plowed into a nearby field. Another followed. And another. Eventually a barrage, accompanied by rifle fire. It was about 11 a.m.

The federal soldiers now scrambling for cover were on the first leg of the Peninsula Campaign. Their column—in concert with a second force moving on a parallel road 12 miles to the south— was heading for Richmond, now 60 miles away. In all, 67,000 soldiers commanded by Maj. General George B. McClellan were marching up a peninsula to attack the Confederacy’s capital. McClellan’s men recently had traveled south to Ft. Monroe by boat, and additional troops were arriving there to join the campaign. Before going further, however, the Yankees had to take Yorktown.[i]

Many 1st Regiment letters and journals described the engagement’s opening shot. “I heard the report of a gun and a shell came sizzling along just over my head and struck about a hundred feet beyond us,” wrote Sgt. George A. Marden, one of those facing Confederate fire for the first time. “I don’t believe I shall ever forget that. I must say I made a reverential obeisance [bow], first to the right and then to the left and then to the centre” Another Sharpshooter’s letter described the sound of that first incoming round: “hooney whiz scream whiny rattle a shell right over our heads and down among the cavalry in our rear and the ball is opened.”[ii]

The “ball” would not end until about 9 p.m. The standoff in front of the Yorktown’s fortifications that followed— pitting McClellan’s forces against the Confederate Army of the Peninsula— continued until the town’s outnumbered defenders stole away, on the night of May 3. By successfully delaying the Union advance for a month, the Southerners enabled their comrades in Richmond to reinforce and fortify the city.*

While the siege has been widely studied in Civil War literature, most accounts dismiss the April 5 fighting that preceded it as insignificant. As Sharpshooter George Hastings observed in a letter home: “It was not an action but amounted to no more than a reconnaissance in force, a more feeling of the enemy’s strength and ascertaining his position.”[iii]

The day’s events deserve closer consideration. This “reconnaissance in force” was complex and dangerous. The engagement of April 5 measured the Sharpshooters’ skill and mettle while under fire. Examining who the men of the U.S.S.S. were, how they trained and how they performed in in the field— fresh off the boat from their Camp of Instruction in Washington— helps to explain why the regiment went on to play an important role in the siege, on the campaign and in future battles. The soldiers’ reflections— excerpted here from an assortment of letters, diaries, and memoirs— tell the untold story of April 5 at Yorktown. The soldiers’ writings candidly reveal how they individually responded when thrust into their first combat, as well as what they thought and felt in the aftermath of the fight.

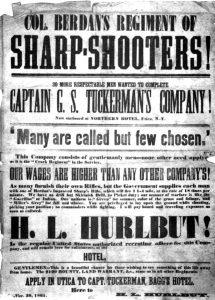

While companies of sharpshooters were attached to some U.S. Army infantry regiments (such as the 22nd Massachusetts and the 16th Michigan), the 1st and 2nd U.S.S.S. were the only Army regiments consisting entirely of expert marksmen. The idea for the Sharpshooters originated with Hiram Berdan. Although he had no previous military experience, the successful businessman and nationally-recognized target shooting champion reasoned that regiments of skilled riflemen, armed with state-of-the-art, long-range weaponry, would inflict heavy casualties on the enemy. He proved an excellent salesman. After meeting with President Lincoln and gaining a letter of support, in June of 1861, Berdan’s proposal to form the 1st U.S.S.S. was approved quickly by the Army. Permission to start recruiting for the 2nd Regiment soon followed. The men were popularly referred to as “Berdan’s Sharpshooters.”[iv]

To be admitted to a U.S.S.S. regiment, a hopeful recruit first had to land ten consecutive rifle shots within a target circle ten inches in diameter, firing from a distance of 200 yards. When training, the men learned tactics that broke with the army’s emphasis on using mass firepower. Rather than stand or kneel shoulder-to-shoulder to fire en masse, they maneuvered to maximize marksmanship skill. Companies broke apart into smaller units and individuals often took up solitary positions or acted as scouts. A newspaper article written as the Sharpshooters were forming stated that the men would be taught to operate on a battle’s “outskirts,” where they “will act independently, choose their objects, and make every shot tell.”

The weapon the Sharpshooters were promised when they enlisted— the breech-loading Sharps Rifle— was very accurate and could be loaded and fired three times faster than the muzzle-loading rifles used by Union and Confederate infantry. For a variety of reasons, however, the Army did not procure the Sharps Rifles for the U.S.S.S. in time for the beginning of the Peninsula Campaign. Berdan’s men instead were issued Model 1855 Colt 5-shot .56 caliber revolving rifles.** These weapons also had a higher rate-of-fire than infantry muzzle-loaders.[v]

All the men in the 1st Regiment’s Companies E and C and a smattering of Sharpshooters in other companies carried their own long-range target rifles. Many of these heavy but deadly-accurate muzzle-loaders were equipped with a telescopic sight when they were manufactured. The Morgan James Rifle was one of the more popular weapons, but a variety of target rifles were used.[vi]

U.S.S.S. uniforms also were different from standard Union issue, dyed green instead of blue. In woods and fields—where the unit often operated— the green clothes served as camouflage. On an open battlefield, they stood out amongst their blue-jacketed comrades, making them easy to identify in the heat of battle and to assign where needed most.[vii]

As the Yorktown siege progressed, Confederate soldiers took note how effectively the green coats wielded their special rifles, and the men of the U.S.S.S. became priority targets. It was common knowledge, one 1st Regiment soldier wrote, that “the rebels will give no quarter to Sharp Shooters.” Some of the marksmen minimized the dangers of being picked off by “dressing so [the enemy] cannot tell us from the infantry,” he continued. Later in the war, the southern press would start referring to the marksmen as snakes in the grass and green demons. One newspaper article would editorialize “they are nothing but murders creeping up & shooting men in cold blood & should receive the fate of murders.”[viii]

When that first Confederate artillery shell flew overhead at Yorktown, the Sharpshooters were in what one of the men wrote was the “post of honor,” at the head of the march. The 1st Regiment quickly transitioned from being first in the column to first into the fight. The special skills and tactics that the men had trained to master at their Washington D.C. Camp of Instruction finally were about to be tested.[ix]

To be continued…

Notes:

* There is not space here to examine the dynamics of the Siege of Yorktown. Briefly, McClellan’s massive seaborne invasion force had started landing at Ft. Monroe in late March. By mid-April, the Army of the Potomac would have 120,000 men in Southern Virginia. The two inland-bound columns on April 5 encountered a 16-mile-long chain of defensive works that spanned the peninsula, from Yorktown to the James River. Although the Confederate commander at Yorktown, Maj. Gen. John B. Magruder, ultimately would be reinforced, on this day he had only 15,000 men to defend his entire line. Magruder tricked the Yankees into thinking they were the ones outmanned and outgunned, pushing McClellan to opt for siege tactics. For more information on Magruder’s successful ploy, see To the Gates of Richmond: The Peninsula Campaign (New York: Ticknor & Fields, 1992), by Stephen Sears, pp. 35-39.

** Although the Colt rifles had a higher rate-of-fire than muzzle-loading rifles, their revolving cylinder could overheat and “chain fire” in multiple cylinder chambers, injuring the soldier holding it. The Sharps Rifles were delivered just after the siege of Yorktown ended, in early May, to the delight of many Sharpshooters, who carried the weapons for the war’s duration. The Colt and Sharps rifles not only fired faster than standard-issue Springfield rifle-muskets, they also were more than three times as expensive. As a result, relatively few were distributed to Union troops.

Sources:

[i] Stephen Sears To the Gates of Richmond: The Peninsula Campaign (New York: Ticknor & Fields, 1992) 35-37.

[ii] George Marden, U.S.S.S., Civil Car letters, April 6 (archived in Rauner Special Collections Library, Dartmouth college, Hanover, N.H.); Charles Seaton, 1st U.S.S.S., Co. F, U.S.S.S., Private Collection.

[iii] George Hastings, Co. H, 1st USSS in a letter to “Lillie,” April 12, 1862 (Missouri History Society, St. Louis, Mo., Lillie Devereux Blake Letters 1847-1886) http://mohistory.org/collections?text=George%20Hastings&collection=Lillie%20Devereux%20Blake%20Papers,%201847-1986&images=0).

[iv] Hiram Berdan, letter to Lt. Gen. Winfield Scott, June 13, 1861 (quoted in Roy Marcout, U.S. Sharpshooters: Berdan’s Civil War Elite (Mechanicsville PA: Stackpole Books, 2007), 9.

[v] Roy M. Marcot, U.S. Sharpshooters: Berdan’s Civil War Elite (Mechanicsville PA: Stackpole Books, 2007) 8-12; Correspondent, New York Post, June 4, 1861, quoted in Marcot, 9; Lt. Col. William V.W. Ripley, Vermont riflemen in the war for the union, 1861 to 1865 A history of Company F, First United States sharp shooters (Rutland,VT; Tuttle & Co., 1883, reprinted by Leonaur Ltd, 2011) 2-8.

Marcot, 55-59.

[vi] Marcot, 57

[vii] Ibid., 33-36

[viii] J.B. Delbridge, April 19, 1862 letter to the Wolverine Citizen, Flint MI (Michigan State University Library archives, Lansing, Michigan); Richard Pindell, “The Most Dangerous Set of Men,” Civil War Times Illustrated, August, 1993, p.46, quoted in Drew Gilpin Faust, This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War (New York; Alfred A. Knoph, 2008) 42-43; Petersburg newspaper originally quoted in William Green’s letter to his mother, transcribed in William H. Hasting’s Letters from a sharpshooter : the Civil War letters of Private William B. Greene, Co. G, 2nd United States Sharpshooters (Berdan’s) Army of the Potomac, 1861-1865 (Historic Publications, Belleville, WI) 226.

[ix] William Sankley, Co. B, April 7 letter to the Albany Evening Journal, April 15 issue (Library of Congress, retrieved at www.fultonhistory.com); Capt. C.A. Stevens, Berdan’s United States Sharpshooters In The Army Of The Potomac (St. Paul, Minn.; The Price McGill Company, 1892, reprinted by Old South Books), 37-38.

4 Responses to Trial by Fire for the U.S. Sharpshooters at Yorktown, Part 1