Unvexed Waters: Mississippi River Squadron, Part 2

Part I of this post introduced the unprecedented U.S. Army Western Gunboat Flotilla—soon to be reorganized as the U.S. Navy Mississippi River Squadron—and carried it through the victorious battles of Forts Henry and Donelson, Tennessee, in February 1862.

The next Union objective was the northern stopper in Rebel defenses of the mighty Mississippi: Island No. 10 near New Madrid, Missouri.

This enlarged sandbar at the bottom of a tight river U-turn mounted five batteries and 24 guns backed up with 7,000 Confederates. Navy Flag Officer Andrew H. Foote supported Major General John Pope against the obstacle in March and April.

Three weeks of furious bombardment by Foote’s gunboats along with rafts mounting 13-inch mortars achieved no results. Foote was hesitant to expose his ironclads to heavy shore guns again after suffering severe damage at Forts Henry and Donelson. Going downriver with the swift current was a whole lot easier than coming back up. The cumbersome vessels could be disabled and captured, and possibly turned against friendly river cities.

But Captain Henry Walke of the USS Carondelet insisted he could make it. The ironclad was covered with rope, chain, and whatever loose material lay at hand. A barge filled with coal and hay was lashed to her side. Her steam exhaust was diverted from the smokestacks out the side of the casemate to muffle sound.

On a moonless night under a thunderstorm, Carondelet slithered downstream unscathed and almost undetected. Another ironclad gunboat followed. The dramatic passage introduced a new, and previously unthinkable, naval tactic: driving vulnerable warships through narrow channels past heavily armed fixed emplacements.

Once past the batteries, the gunboats ferried Union forces across the river below the island, isolated and captured the outnumbered garrison from behind. This process would be repeated on a larger scale three weeks later at New Orleans, and subsequently at Vicksburg, Port Hudson, and Mobile.

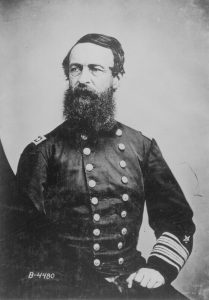

Flag Officer Charles H. Davis relieved Foote as flotilla commander in May 1862 and headed on downriver for Memphis with six ironclads, accompanied by Colonel Charles Ellet and his nine unarmed wooden rams.

Confederates had seized a motley collection of passenger, cargo, and tow boats to defend the river, converting them to rams armed with one or two guns—the Confederate River Defense Fleet. Like the Ellet rams, these were captained and crewed by civilian rivermen, nominally under army command, but operating independently and with little coordination.

Five of the swift Rebel steamers surprised and rammed the lumbering Union ironclads Cincinnati and Mound City at Plum Point Bend above Memphis on May 10. Both vessels were grounded and sunk in shallow water but were soon raised and placed back in service.

On June 6, eight of the Confederate converted paddlewheelers steamed out to defend Memphis cheered on from the bluffs by hundreds of citizens. After an inconclusive, long-range gunnery duel, the impatient Colonel Ellet, on his own initiative, charged through the ironclad line in his Queen of the West and struck the first Rebel vessel encountered, sinking it immediately, only to be rammed himself by another. The ram Monarch followed, while the ironclads closed to deadly range.

A raging melee erupted with no command coordination on either side. The Rebel squadron, unarmored and outgunned, was destroyed, marking the near eradication of Confederate naval presence on the river.

This was the only “fleet action” of the war, the last in which ramming was a primary tactic, and the last time civilians with no military experience such as Charles Ellet commanded ships in combat. Ellet’s ram fleet would become the Mississippi Marine Brigade under navy direction, employed primarily for amphibious raiding and support tasks.

The loss of Memphis, the Confederacy’s fifth-largest city and key industrial center, opened the Mississippi all the way to Vicksburg and opened West Tennessee to Union occupation.

But strategic opportunity was lost as attempts to reduce Vicksburg from the river that summer of 1862 failed for lack of army support when the indecisive Major General Henry W. Halleck became bogged down in the siege of Corinth, Mississippi.

Then a major reorganization transferred the Western Gunboat Flotilla to command of the navy and re-designated it the Mississippi River Squadron with a new and aggressive rear admiral, David D. Porter, in command.

Halleck was called to Washington and Major General U. S. Grant took over the Army of Tennessee.

Porter and Grant made a winning ream, melding the strategic flexibility of maritime power—within its limitations—with hard and smart fighting on land. But it was a learning process. In late December, Grant sent W. T. Sherman downriver with a major amphibious force for a landing at Chickasaw Bayou northwest of Vicksburg, only to be repulsed with heavy casualties.

That winter and spring, Grant conducted a series of fruitless operations to outflank the city by cutting canals, blowing up levees, flooding the Mississippi Delta, and pushing ironclads, gunboats, and troop transports through tiny, choked channels that must have resembled the upper Mekong in “Apocalypse Now.”

The general wrote in his memoirs that these efforts were intended primarily to keep his troops busy during the flooded and disease-ridden winter and that he had no expectation of success. This claim appears to be contradicted by his contemporary correspondence.

Grant’s final option was to march the army through the swamps down the west bank of the Mississippi, cross south of and get behind Vicksburg. Porter would have to sneak his gunboats and transports downriver past powerful Rebel batteries on the bluffs to accomplish the army crossing. This would be a one-way run. If the squadron survived the transit, it would be suicidal to steam back up against the swift current.

On April 16, 1863, a clear night with no moon, seven gunboats and three empty troop transports loaded with stores ran the gauntlet. Despite efforts to minimize lights and noise, the bluffs exploded with massive artillery fire. Confederates set bonfires along the banks to illuminate the scene. Union gunboats fired back.

The Union column hugged the east bank–so close they could hear rebel gunners shouting orders–to get under the line of fire with shells zinging overhead. On April 22, six more boats loaded with supplies made the run. The squadron incurred little damage with two transports lost, thirteen men wounded, and none killed.

Grant ferried his army across, laid siege to and captured the “Gibraltar of the West.” It was arguably the most brilliant campaign of the war, at least as important as the simultaneous victory at Gettysburg. The Mississippi River Squadron backstopped the army, closed the river, and provided continuous heavy artillery support. The fall of Port Hudson, Louisiana, the last Confederate stronghold on the river, followed quickly.

“The father of waters again goes unvexed to the sea,” wrote Abraham Lincoln. Other than the abortive Red River campaign in spring 1864, there would be no more major river engagements. But the Mississippi River Squadron would be busy for two additional years fighting Rebel guerrillas, suppressing enemy trade, and protecting friendly commerce.

(Extracted from a paper presented at the North American Society for Oceanic History (NASOH) Annual Conference, St. Charles, Missouri, May 22, 2018. This presentation with PowerPoint is available for interested groups. See www.CivilWarNavyHistory.com.)

Much like the seldom visited site of the 1942 Battle of Midway, the site of the joint operation against Island No.10/New Madrid suffers because there is no National Military Park established, so no opportunity exists for interested parties and school students to visit the scene of one of the most important, and certainly most interesting, campaigns of the Civil War. Without “a place” to visit (such as Gettysburg, Shiloh, Vicksburg) even scenes of great importance fade from public memory, which is a shame, because Island Number Ten involved:

– first use of 13-inch mortars lobbing 128 lbs. shells 2 1/2 miles

– the digging — and successful use — of an innovative canal (Bissel Canal)

– Robert’s Raid to take out the most important Rebel gun, allowing

– the Run of the Carondelet, followed by

– the Run of the Pittsburg.

– Along the way, a raid was conducted against Union City Tennessee (benefiting U. S. Grant’s operation against Rebel railroads, based at Pittsburg Landing)

– and a balloon was put to use with pilot John Steiner and an Army artillerist observing the fire of 13-inch mortars and correcting the timing of the explosive shells.

Thanks to Dwight Hughes for bringing the important story of Island No.10 to our attention.