All Star President of the New York Mutuals Captain Jack Wildey–Part 2

When the 11th New York got back to Washington and took stock of their situation, it did not look good: almost seventy men had been sent to Richmond as prisoners and as many as 177 were lost to action. At least thirty-five had been killed outright with more to soon die of their wounds. On August 12, 1861, the remaining members of the regiment were sent back to New York City to disband in preparation to reorganize, obtain equipment and recruit replacements.[1]With Captain Wildey’s fame preceding him, he rode home with his mates.

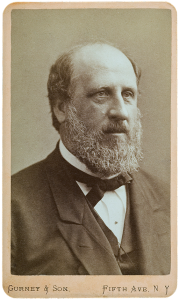

Although most of New York’s firefighters who fought for the Union supported Lincoln’s cause, they were, for the most part, Democrats. New York Mayor Fernando Wood was a notorious Confederate sympathizer and in order to get and retain loyalty in the city, Lincoln’s future Secretary of War Edwin Stanton (a Democrat before 1862) was tasked to make deals with whomever he could. This included Tammany Hall and William Magear “Boss” Tweed. Basically, the deal was this–toss some support to Lincoln in exchange for a couple of lucrative government contracts.[2]

In New York’s 1861 fall elections, Tweed needed people to run in some specifically designed “fusion” tickets that united Tammany Democrats with Lincoln Republicans. Tweed designed the race so that his candidates were entered in weak areas, assuring a win for Tammany Hall. Included in the fusion ticket sweep of offices was John Wildey, a candidate for City Coroner. Although the office of Coroner seems like an odd choice for a former Union army infantry captain, it must be pointed out that being a coroner in New York City at the time was a political endeavor, not a medical one. Coroners were paid by the dead body, and few questions were asked about how the body came to be dead. If the remaining family members chose to have their loved one buried by a Tammany-owned funeral home, the coroner got an even bigger kickback. Wildey owed his political career to Tweed, so it is likely that he was a willing participant in the corrupt coroner process. The New York Times 1889 obituary of Wildey states with a trace of irony: “He died in poverty. He had made plenty of money, but long ago lost the last of his fortune.”[3]He did not make that fortune as a fireman, a Civil War veteran, or in baseball.

And just what did Tammany politics have to do with baseball? William L. Riordan quotes George Washington Plunkett in his book Plunkett of Tammany Hall:

I hear a young feller that’s proud of his voice… I ask him to join our Glee Club. He comes up and sings, and he’s a follower of Plunkitt for life. Another young feller gains a reputation as a baseball player in a vacant lot. I bring him into our baseball club. That fixes him. You’ll find him working for my ticket at the polls next election. I rope them all in by givin’ them opportunities to show off themselves off. I don’t trouble them with political arguments.”[4]

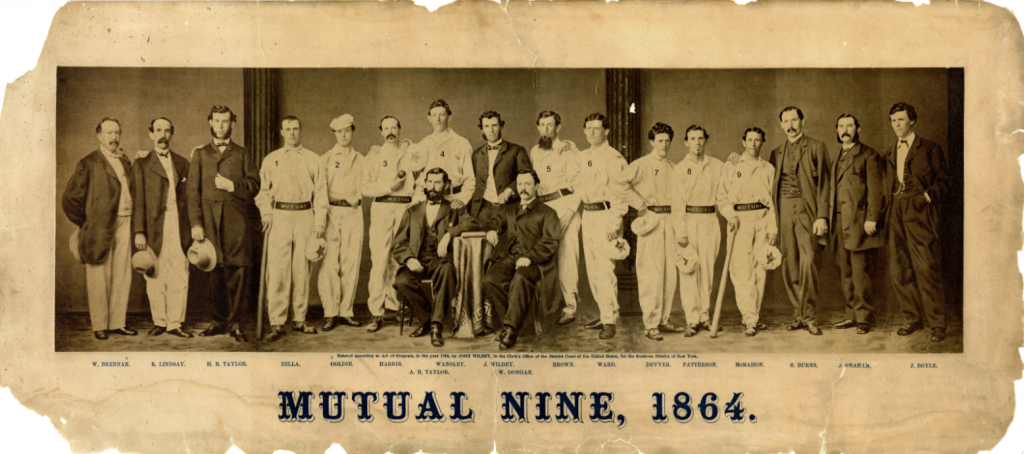

John Wildey’s Coroner’s Office found employment for many players in the New York Mutuals. Within a few years, Tammany Hall was contributing generously to the upkeep of New York’s most successful “amateur ” team. In 1862, many of the Mutuals players were on salary, although not in a way that could quickly be traced back to the team itself.

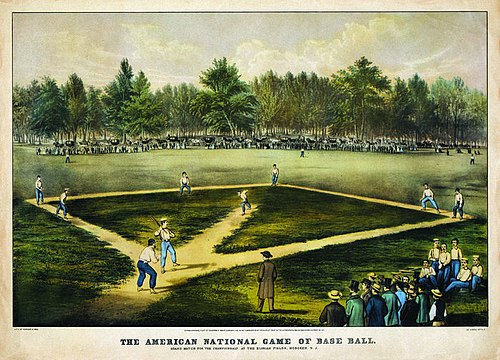

In 1865, the National Association of Base Ball Players (NABBP) met for the first time since the Civil War. Clubs gathered from ten states to elect New York Coroner/Civil War hero John Wildey as their national president.[5]Baseball was facing two huge problems at the time: whether or not the amateur, volunteer teams should become professional, and gambling. The Mutuals were not known for their honesty in baseball. Players had been receiving money for their efforts for several years in one way or another, and cheating on a game in which large bets were placed was not unknown. When there was cheating to be done, the Mutuals could be counted on to cheat in grand style. They were avid bettors and sore losers.[6]

The first generally considered “thrown” game was the contest between the Mutuals and the Eckford Club of Brooklyn on September 28, 1865. During the first four innings, the Mutuals played like the favorites they were. Gamblers moved through the crowds, making and collecting bets. In the fifth inning, things on the field changed dramatically–the Eckfords scored eleven runs! Games could be high scoring in the days when fielders, for example, had no baseball gloves and catchers were getting battered by trying to bare-handedly catch pitched balls, but it was the suspicious way that the runs were suddenly accumulated. Experienced Mutuals catcher William Wansley had missed two catches, had six passed balls and four wild throws one after the other.[7]

Daniel E. Ginsberg, in The Fix Is In: A History of Baseball Gambling and Game- Fixing Scandals, describes how catcher Wansley talked two more Mutuals players–Ed Duffy and Tom Devyr–into helping him throw the game against the Eckfords. Certain gamblers were informed of this new “condition,” and the fix was now a going concern. After the game, President Wildey facetiously chastised Wansley with “willful and designed inattention” as he played and, with the confession of Devyr, all three players were suspended from baseball.[8]In this way the Mutuals-Eckfords match officially became the first rigged game in the history of the sport. This was not some obscure contest. It involved the top teams in the largest city in the nation. New York was considered the cradle of baseball, and the majority of the amateur teams were in the New York metro area. This game had been thrown on the “biggest baseball stage in the country.”[9]Do not think for a moment that Wildey was not involved from the beginning.

City Coroner and former Captain John “Jack” Wildey had one more contribution to make to baseball, although this one was more honorable. He championed the return of Duffy, Wansley, and Devyr and by 1870 all three were back on the diamond. On November 30, 1870, Wildey was again elected President of the NABBP by a vote of 18-8. The organization also voted by a 2-1 margin to become professional. Wildey was completely in favor of this move. After all, the Mutuals had been illegally professional for years. His response to those who were loath to abandon their original amateur status was:

City Coroner and former Captain John “Jack” Wildey had one more contribution to make to baseball, although this one was more honorable. He championed the return of Duffy, Wansley, and Devyr and by 1870 all three were back on the diamond. On November 30, 1870, Wildey was again elected President of the NABBP by a vote of 18-8. The organization also voted by a 2-1 margin to become professional. Wildey was completely in favor of this move. After all, the Mutuals had been illegally professional for years. His response to those who were loath to abandon their original amateur status was:

We are perfectly willing to adopt such a rule, but I fear, ladies and gentlemen, if we did, the players wouldn’t observe it. It seems to me that the days are over when baseball is purely a game for amateurs.[10]

Four years before Wildey’s death, a history of the New York City fire departments concluded their biographical sketch of him with:

Everyone knows of Jack Wildey of ‘Black Horse Guard’ fame. He was always a great admirer of athletic sports of all kinds, and, although sixty-two years old, he would astonish some of the present generation should they try their strength against him.[11]

Captain John Wildey, of New York City’s Engine Company Number 11, of Tammany Hall, of the New York Mutuals, and of the 11th New York Fire Zouaves died in 1889. His obituary, although short, does not fail to mention that, “… in the Battle of First Bull Run he contributed by his bravery to saving the colors of the Sixty-ninth Regiment from capture by the rebels….”[12]

That, and baseball.

_________________________________________

[1]”Reports from Alexandria,” August 31, 1861: The New York Times.

[2]Kenneth D. Ackerman, Boss Tweed, (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 2007), 27.

[3]”John Wildey Died in Poverty,” Obituary, June 1, 1889, The New York Times.

[4]William R. Riordan, Plunkett of Tammany Hall: A Series of Very Plain Talks (New York” E. P. Dutton & Co., 1963) 25-26.

[5]William J. Ryczek, When Johnny Comes Sliding Home: The Post-Civil War Baseball Boom, 1865-1870, (Jefferson, North Carolina and London, McFarland & Company, Inc., 1998), 247.

[7]Philip H. Dixon, “The First Fixed Game: Mutuals of New York vs. Eckfords of Brooklyn,” Inventing Baseball: The 100 Greatest Games of the 19th Century, (SABR, 2013); 46,47.4

[9]Mark Souder, “Captain John Wildey, Tammany Hall, and the Rise of Professional Baseball,” [online version available through https://sabr.org/research/captain-john-wildey-tammany-hall-and-rise-professional-baseball].

[11]Frank Kernan, Reminiscences of the Old Fire Laddies and Volunteer Fire Departments of New York and Brooklyn, Together with a Complete History of the Paid Departments of Both Cities, (New York: M. Crane, 1885), 474. [online version available through https://archive.org/details/reminiscencesol00kerngoog].

[12]Obituary, “John Wildey Died in Poverty,” June 1, 1889, The New York Times.

There has to be some serious research to find this information. For a few moments in John Wildey’s life he fought the Confederacy, but much of his life he had to deal with real decisions in New York City: corrupt politicians, sports, everyday struggles and to survive in the post Civil War years of the Gilded Age. The Civil War gave and took away opportunities for advancement. With the transcontinental railroad completed in 1869, baseball the “National Pastime” spread throughout the North, South, and West. Whatever your political party, region, or personal preference, sports, and especially basebal, has been a unifier for the United States of America. It has been nice to get tup his morning and have my coffee and read about the Civil War, and baseball, since its my favorite sports to read about and later today watch the All Star Game with the author of this article. lol

My favorite fan!

A very interesting story, a precursor to the infamous Chicago “Black Sox” throwing the 1919 World Series (“Say it ain’t so, Joe”). Was cheating a widely accepted practice in Wildey’s time? And was anyone ever accused and legally prosecuted for it, do you know? Eight of the White Sox were.

Cheating was frowned upon, but it was not the scandal it became by 1919. After ball players became professional, it was a much bigger deal. One thing I have learned by studying this period is that sometimes things like cheating, graft, money laundering, etc. were much more casual crimes than they are today. It is an interesting topic. Organizations like Tammany provided social services for immigrants that the U. S. government did not provide. I think the quote from Plunkett of Tammany Hall is very enlightening. Thanks for bringing this up.

As usual Meg, an outstanding piece of research and writing. Far too often we overlook these boys as people off of the battlefield with real lives and interests other than tearing each other apart.

– Michael Aubrecht