Foraging With The 1st West Virginia Artillery

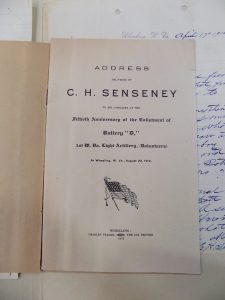

In August 1912, C.H. Senseney delivered an address on the fiftieth anniversary of the enlistment of Battery D of the 1st West Virginia Artillery. His reminiscence speech was later printed and bound in a booklet form, and I was lucky to see the copy preserved in the archive at Virginia Military Institute.

In August 1912, C.H. Senseney delivered an address on the fiftieth anniversary of the enlistment of Battery D of the 1st West Virginia Artillery. His reminiscence speech was later printed and bound in a booklet form, and I was lucky to see the copy preserved in the archive at Virginia Military Institute.

Along with regimental history, Senseney shared some stories about the artillerymen’s life and experiences on campaigns and in camps. Here’s an overview of the battery’s history and a few stories about foraging for food on the march.

Battery D was organized on August 20, 1862, in Wheeling, West Virginia, and served in the District of West Virginia/Department of Ohio until January 1863. That year the battery transferred to General Robert Milroy’s command and encamped near Winchester, Virginia and were involved in the Battle of Winchester. They maneuvered against Confederate cavalry commanded by General Rosser and joined Union General Sigel’s army for the New Market battle and campaign in the spring of 1864. The battery – commanded by Captain John Carlin – advanced up the Shenandoah Valley with General David Hunter, fighting at Piedmont, Lynchburg, and during the march back through West Virginia. The unit remained in West Virginia until they mustered out of service in June 1865.

Charles H. Senseney revealed some entertaining moments as members of his battery stole food during their advances in the Shenandoah Valley. The following two incidents made this researcher chuckle while trying to image the scenes.

One evening while at Clarksburg I was lying in my tent, not feeling well, when I heard Jim Mills tell some of the boys that down near the town he saw a fine, fat pig lying in a manure pile, and Mills said that when it got dark it would be a good thing to get some fresh pork. The boys agreed with him. Jim got an axe and he told the boys that he would hit Mr. Pig so hard that he would not grunt. They went off and in about half an hour they returned laughing. I asked Jim what was the matter, and he replied, “I hit him on the wrong end.”

Imagine that squealing scene in the barnyard and the thieving artillerymen tumbling over each other to get away before that farmer came out to see what was the matter…

Imagine that squealing scene in the barnyard and the thieving artillerymen tumbling over each other to get away before that farmer came out to see what was the matter…

Animals making noises to give away the situation seemed to be a trend since it happened again:

On our way back to Beverly, some of our squad picked up a goose and put him in a [cold] Sibley stove that we had on our caisson. Finally the goose began to squak. Captain Carlin rode by our caisson but failed to find the goose. As soon as we got a chance, the goose lost his head.

One has to wonder if Captain Carlin knew and chose to overlook the offense or if he was truly mystified by the squawking caisson as he rode along his battery.

One has to wonder if Captain Carlin knew and chose to overlook the offense or if he was truly mystified by the squawking caisson as he rode along his battery.

Other section of the speech offer memories about the rations issued to the artillerymen and how they cooked. Hardtack, cornmeal “pancakes”, bean soup, rice, and coffee are some of the issued foods that Senseney remembered.

These two short accounts about foraging (stealing) give detailed glimpses in the efforts of these soldiers to supplement their ration diet with fresh meat taken from the local civilians. Though foraging was wrong and frowned upon by the officers, the soldiers often viewed it as a necessary adventure to relieve the boring food in camp. In these particular remembered cases, the desperate and surprised animals created rather humorous situations to reconsider.

Interesting, behind the scenes story. It’s great you uncovered it. But it was not so amusing a tale to the central character, “Mr. Pig!” Or, more importantly, to the family that owned it.

Reading soldiers’ letters and diaries, I’ve run across a few “foraging” (thievery, really) stories myself. And stories of Union soldiers paying for or bartering for various food items. Whether they stole or obtained food honestly apparently varied, from campaign to campaign and commanding officer to officer. Also, I suppose, on the level of deprivation and hardship the Union forces experienced at a particular time.