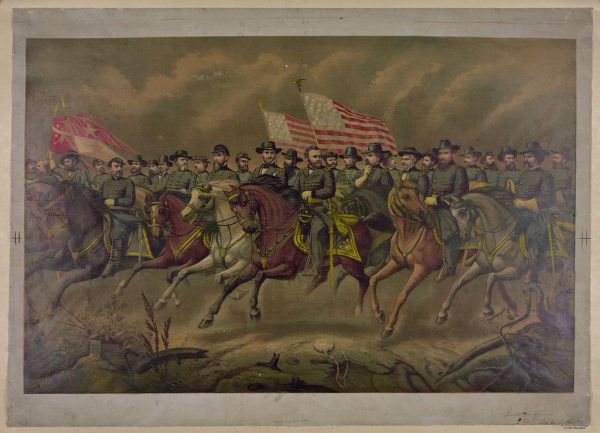

Grant Takes Command In The West

We often think of General Ulysses S. Grant’s “take command moments” in the East – especially at Emerging Civil War which has many members headquartered in the Central Virginia area near Grant’s big battlefields. However, in mid-October 1863, General Grant had another decisive promotion which would offer more Union victories in the West and continue paving the way for his arrival in Washington D.C. and Virginia in 1864.

On October 16, 1863, the Military Division of the Mississippi was created. Grant met with Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, who informed the general of the new military division and impending command. By October 18, Grant held command. Basically, the new commanded encompassed the Departments of the Ohio, the Tennessee, and the Cumberland and included all Union armies between the Mississippi River and the Appalachian Mountains.

Grant’s promotion shifted the commanders and order of battle in the military division. General Sherman commanded of the Department of the Tennessee while General Burnside controlled the Department of the Ohio, and General Rosecrans briefly held the Department of the Cumberland.

One of the Grant’s first actions in his new position: fire General Rosecrans and put General George H. Thomas in command of the Cumberland. Partly in response to troubles back in 1862 and partly due to the Union defeat at Chickamauga, Grant made this decision and had Stanton and Halleck’s approval to change commanders.

With a new military division and department commanders, Grant looked to the maps and military situation in the autumn of 1863. Chattanooga needed relief and the Union hold on east Tennessee dangled precariously. Confederate Generals Bragg and Longstreet could also cause trouble.

Though some of his supporters had lobbied for his immediate transfer to the East, Grant contentedly waited, writing, “My going [to the East] could do no possible good. They had there able officers who have been brought up with that army, and to import a commander to place over them certainly could produce no good.” He continued his considerations. “I can do more with this army than it would be possible for me to do with any other without time to make the same acquaintance with others I have with this. I know the soldiers of the Army of the Tennessee can be relied on to the fullest extent. I believe I know the exact capacity of every general in my command to command troops, and just where to place them to get from them their best services.” [1]

Between October 16 and 18, decisive steps gave Grant a massive district, armies at his command, and daunting military objectives. The stage was set – both in the west and the east. If Grant succeeded in the West, would President Lincoln have found his general to bring east to march on Richmond one last time? History tells us how that question was answered…

Source

[1] Excerpt from a letter from U.S. Grant to Elihu Washburne, quoted from The Man Who Save The Sunion: Ulysses S. Grant In War and Peace by H.W. Brands, page 265.

Minor quibble: Grant was given two orders placing him in this new command, one retaining Rosecrans, one replacing him with George Thomas; Grant chose the latter. I would say that Stanton and Lincoln gave Grant the freedom to choose his command team in his new position, not that they agreed to it a posteriori.

Hi James,

Thanks for pointing this out. We’ve updated the post and hopefully it explains a little more accurately.

Appreciatively,

Sarah Kay Bierle