Indian Aid: Ely Parker and the Surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia

Four months before giving birth to her son Ely, expecting mother Elizabeth Johnson Parker (Gaontguttwus to the Tonawanda Seneca tribe) awoke one night after experiencing a dream. Her mind’s vision showed a rainbow broken in two. The bottom of one half ended at the home of the local Indian agent in Buffalo, New York, while the other half concluded on the Seneca reservation. Unsure of its meaning, Elizabeth Parker sought the help of a dream interpreter. “A son will be born to you who will be distinguished among his nation as a peacemaker,” began the prophesy. “[H]e will become a white man as well as an Indian, with great learning; he will be a warrior for the palefaces; he will be a wise white man, but will never desert his Indian people or ‘lay down his horns as a great Iroquois chief’; his name will reach from the East to the West–the North to the South, as great among his Indian family and the palefaces. His sun will rise on Indian land and set on the white man’s land. Yet the land of his ancestors will fold him in death.”

Ely Samuel Parker came into this world four months later with big shoes to fill. He was born in Indian Falls, New York and bore the Seneca name Hasanoanda, which means Leading Name. Parker initially struggled in his schooling, especially when it came to learning English. He persisted however and quickly rose through the ranks of the Seneca tribe. At age 18, President James Polk even invited him to dinner at the White House.

Despite his rising star, Parker continued to face obstacles as an American Indian. He was denied the ability to practice law so he turned his sharp eye to engineering instead and found it a profitable profession. In 1851, at the age of 23, Parker became the Grand Sachem of the Six Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy.

Having plunged into the worlds of the Indian and the white man, Parker felt compelled to serve when the Civil War commenced. He unsuccessfully tried three times to tender his talents to the United States. Parker even wrote to Secretary of State William Seward who rebuffed Parker’s entreaty. Seward told Parker that the conflict was “an affair between white men… We will settle our own troubles among ourselves without any Indian aid.”

Never one to be deterred, Parker continually searched for ways to serve the United States. Two of his friendships from his time spent in Galena, Illinois served him well–those with Ulysses S. Grant and John E. Smith. The latter placed Parker on his staff with Grant’s endorsement. Following exemplary service at the Siege of Vicksburg, Grant plucked Parker away from Smith and appointed the Seneca Indian to his personal staff.

In a young life already filled with great accolades, Parker’s greatest day came 154 years ago at Appomattox Court House. Though Parker struggled with the English language in his youth, he was now adept at it and was known for his immaculate penmanship. As such, Parker personally penned Ulysses S. Grant’s reply to Robert E. Lee requesting a meeting between the two generals on April 9, 1865. Following the conclusion of pleasantries in Wilmer McLean’s parlor that afternoon, most of Grant’s entourage excused themselves while the surrender proceedings took place. Only a few of Grant’s staff remained by the general’s side. Ely Parker was one of them.

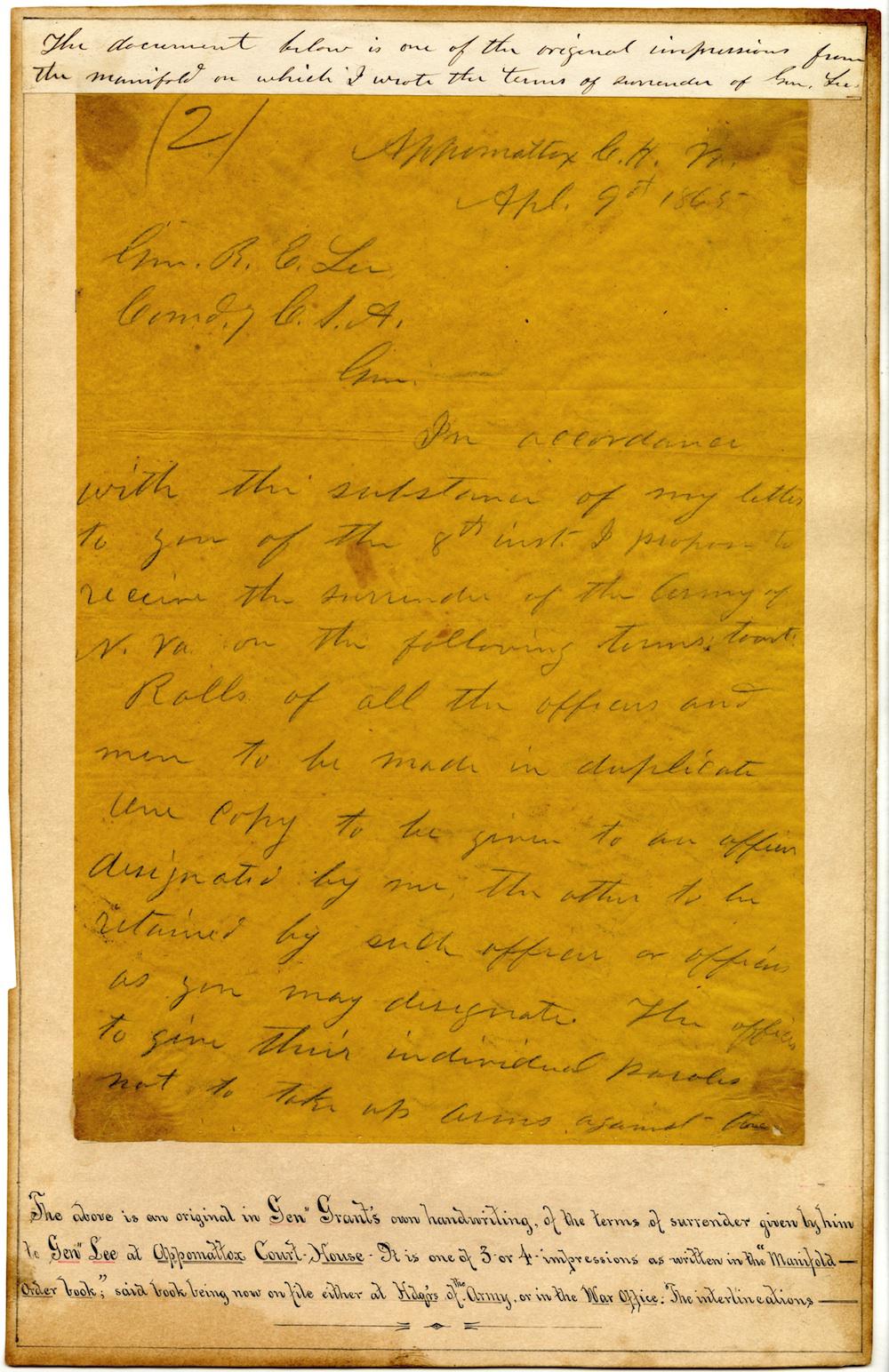

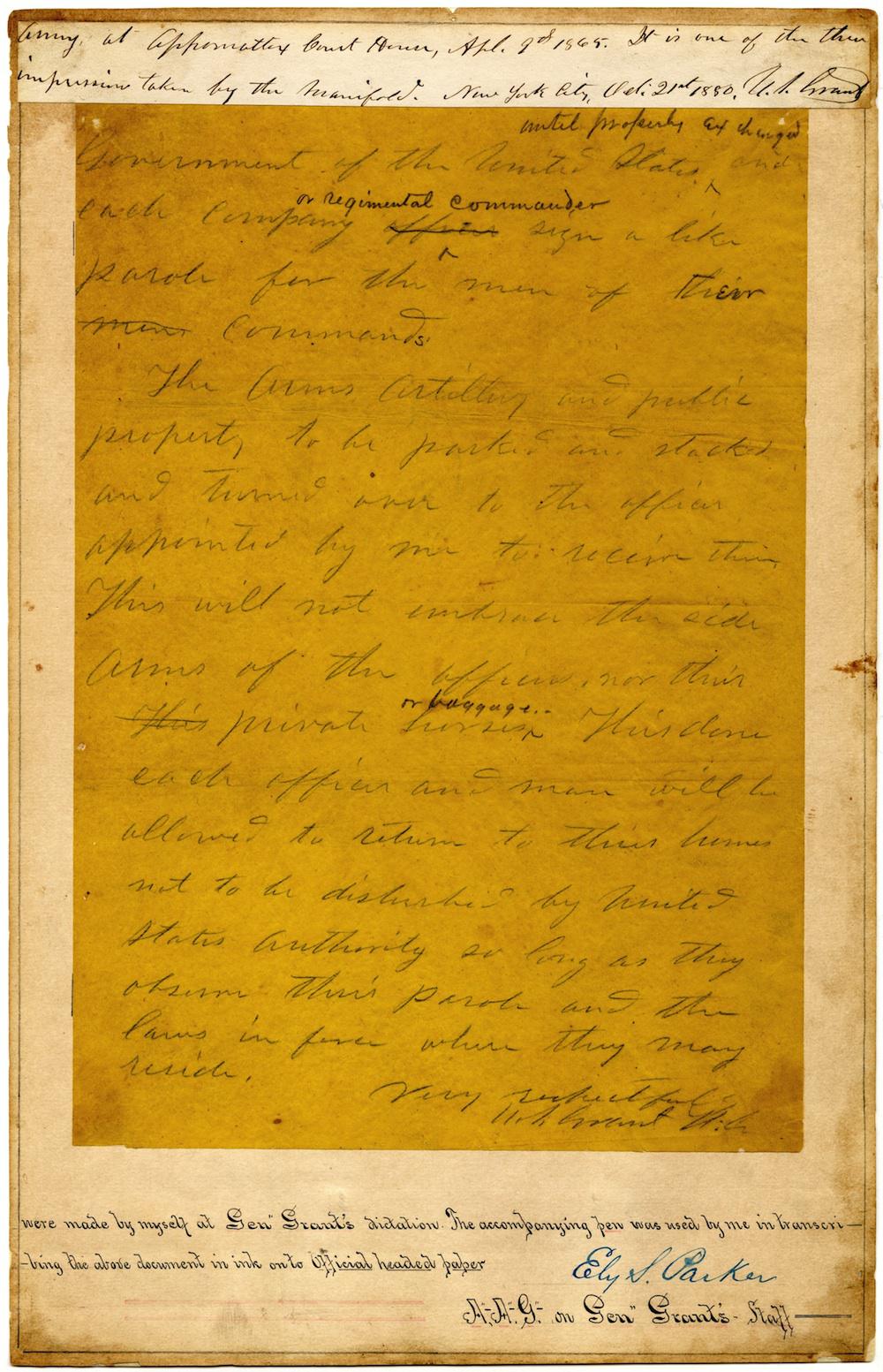

After Grant and Lee agreed to the terms of the Army of Northern Virginia’s surrender, Grant put the terms to paper. He scanned them with Parker peering over his shoulder and the engineer made several amendations to Grant’s handwritten terms. When the time came to prepare the official copies of the surrender document, the general turned not to Parker but to his senior adjutant Theodore Bowers. Nerved by the momentous occasion, Bowers’ hand was too shaky to write the official documents, though. The task became Parker’s, whose penmanship skills churned out the terms of the surrender.

Long after the guns of war fell silent across the former Confederacy, Ely Parker retained one of Grant’s handwritten copies on which the general originally drafted the surrender terms. It was one of his prized possessions from the war.

Following Appomattox, Parker and Grant continued their friendship. Grant stood as Parker’s best man at his wedding and under the Grant administration, Parker fittingly led the Bureau of Indian Affairs. He died in 1895 and lies resting in Forest Lawn Cemetery in Buffalo.

Ultimately, his mother’s dream came true–Parker lies in former Tonawanda Seneca territory. However, William Seward’s prediction that the “affair between white men” could be settled “without any Indian aid” proved grossly false. Parker’s pen firmly inked the ceremonial end of the Confederacy and the end of the Civil War.

Fantastic, just fantastic.

Thanks, Chris!

In 1969, the National Geographic Society published a hardcover book called The Civil War…in the book is the Tom Lovell painting of the surrender…ever since then, i wondered about Colonel Parker and how he came to be a member of General Grant’s staff…now i know! Thank-you.

Thanks for taking the time to read it, Mark!

I have this book still. Carried it around a lot as a kid in the 80s.

Great article! His encounter with General Lee is the best;

In the room of the surrender General Lee saw Eli and stared at him for a moment and then extended his hand and said, ‘I am glad to see one real American here.’ Eli shook his hand and replied back to Lee, ‘We are all Americans.’

Great introduction. Better than I could have done. Could not some information have been presented on how it was that Parker went to Galena, IL and how he came to meet Smith & Grant. And the author chose not to mention REL’s comment to Parker, which was refreshing, everyone else feels compelled to, and if I haven’t read that 100 times I’m uninformed. Mr. Seward should have known that there were many Indians in the ranks “aiding” to settle the issue.

Hi Henry, thanks for reading the article. Parker was an engineer and was assigned a project in Galena in 1857. Grant and Smith were living there at the time and thus the three became acquainted.

Very enjoyable article, Kevin, as always.

Thanks, Gene!

I did program on him for my CWRT, got to talk to his great nephew personally. I admire this man greatly, noted Grant never noted his “friend ” in his memoir