The Lincoln Tragedy In Artwork

On the evening of April 14, 1865, President and Mrs. Lincoln when to Ford’s Theater to see a comedy entitled Our American Cousin. At the theater, John Wilkes Booth slipped into the presidential box, fired a small pistol, then leaped over the railing to make his exit. With a bleeding and unconscious president suffering from a head wound, the evening became a tragedy. A Lincoln Tragedy, An American Tragedy.

The following morning at about 7:22 a.m. Abraham Lincoln died, plunging the already struggling nation deeper into grief and retribution. Members of his cabinet and other political leaders clustered around his deathbed – shocked, grieving, or already plotting their next moves in the governmental power vacuum created by the president’s death.

Through the decades, artists have depicted the deathbed scene and their interpretations have varied through the years. Here are a few examples of the final scene in the Lincoln tragedy:

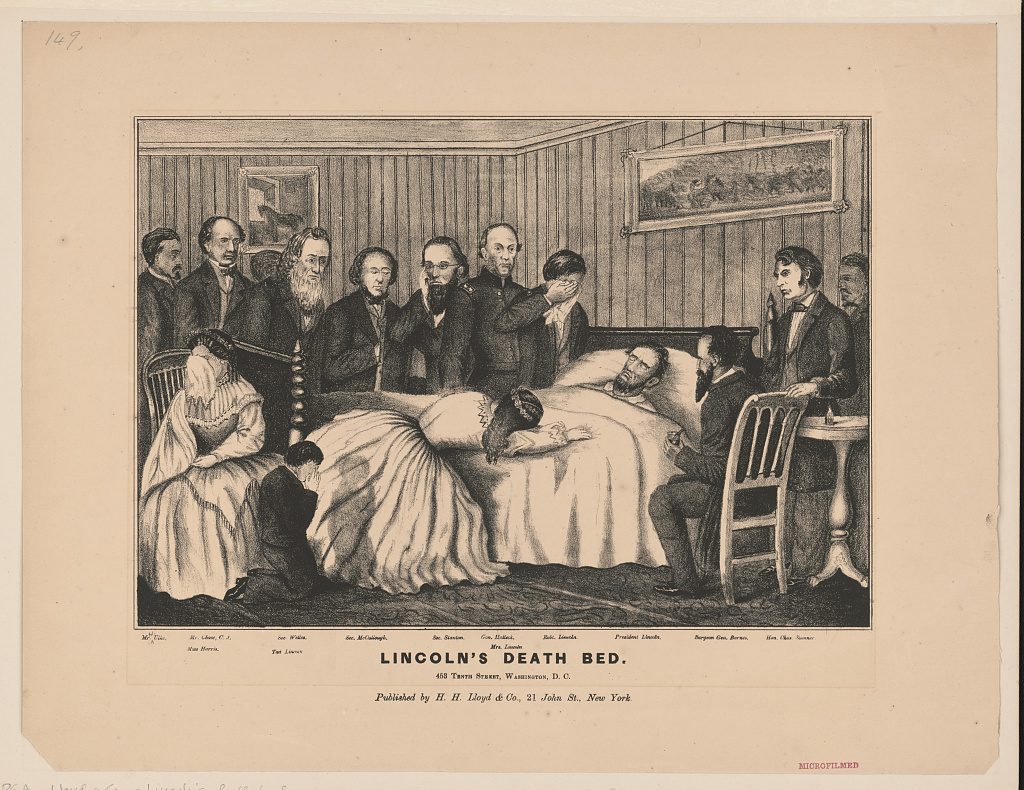

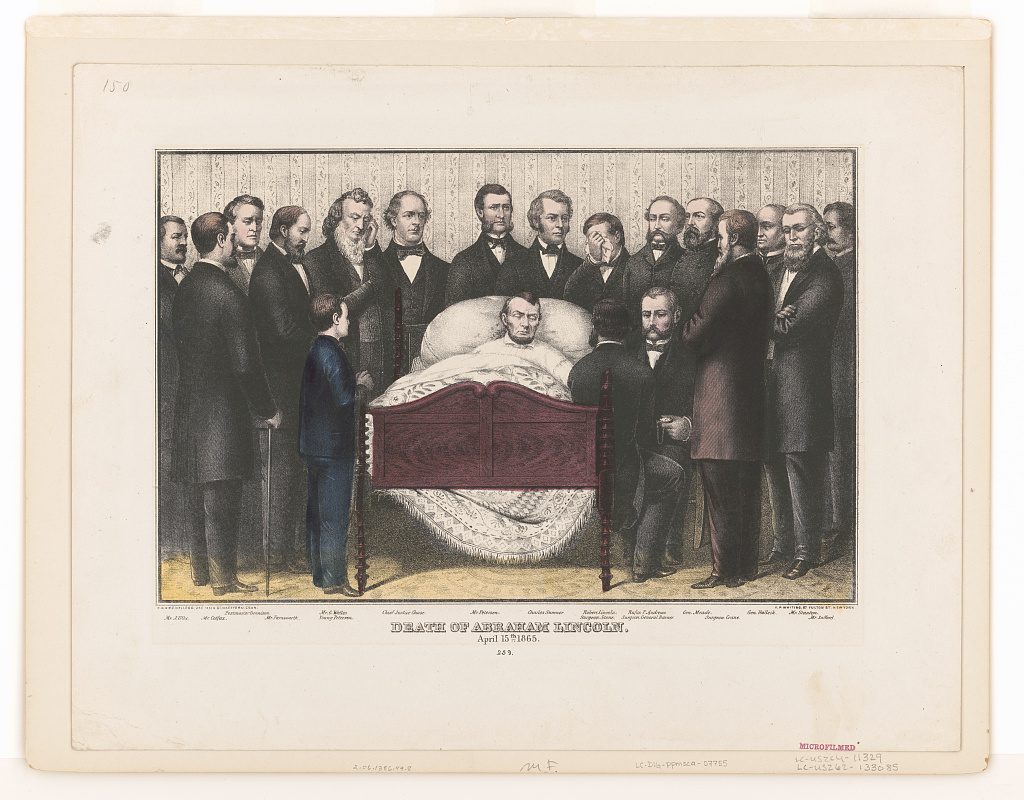

“Lincoln’s Death Bed: 453 Tenth Street, Washington D.C.” is one of the early published illustrations of the April 15th scene. Created and published by H.H. Lloyd & Co in New York, the scene includes family and prominent political figures clustered around the dying executive’s bed. Significantly, the publisher named the figures:

“Mr. H. Utke, Miss Harris, Mr. Chase, C.J., Tad Lincoln, Sec. Welles, Sec. McCullough, Sec. Stanton, Gen. Halleck, Mrs. Lincoln, Robt. Lincoln, President Lincoln, Surgeon Gen. Barnes, Hon. Chas. Sumner.”

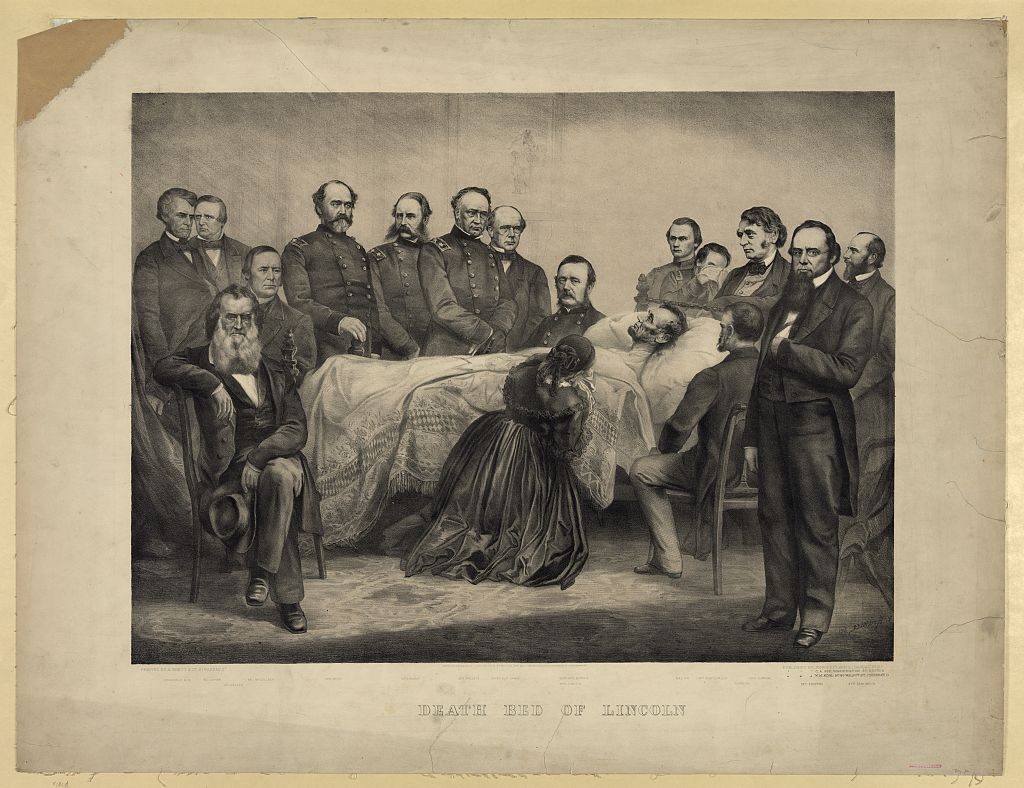

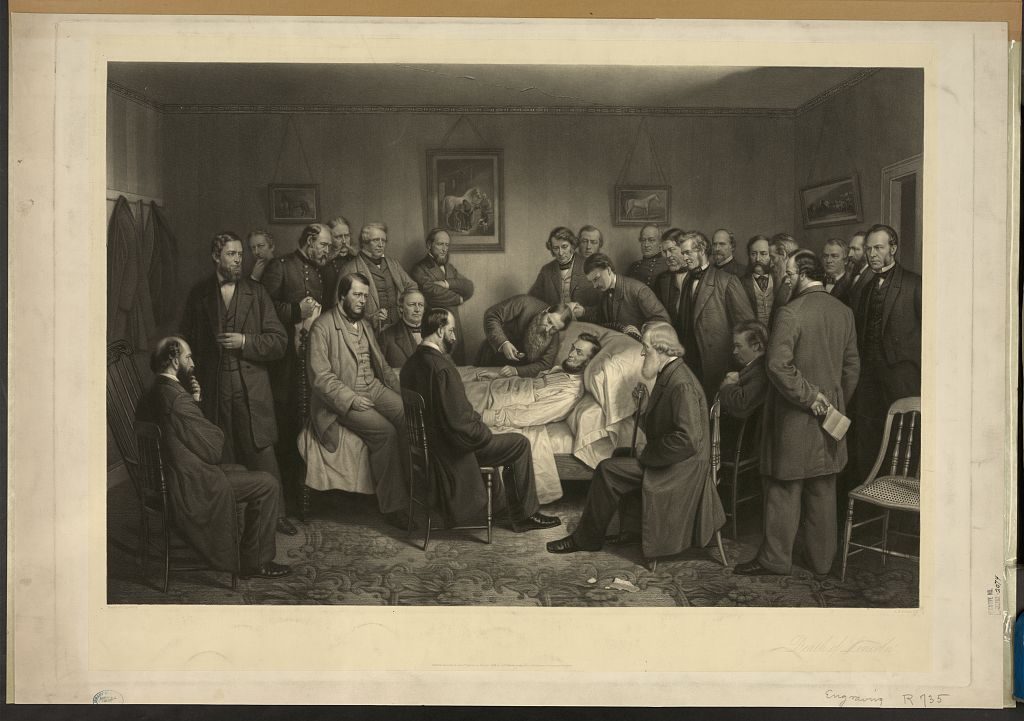

Another 1865 print – this one published by Jones & Clark and A. Brett & Co. – is similar to the previous piece. However, this one adds a strong military presence with generals in uniforms. Mary Lincoln is again shown kneeling and weeping, but Miss Harris is absent.

From left to right: William Dennison, Post Master General, Sec. John P. Usher, Sec. Gideon Welles, Sec. Hugh McCulloch, General Montgomery C. Meigs, General Christopher C. Augur, General Henry Halleck, Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase, Surgeon General Joseph Barnes, Mary Todd Lincoln, Major John M. Hay, Captain Robert Todd Lincoln, surgeon Charles Leale, Senator Charles Sumner, Sec. Edwin M. Stanton, and Attorney General James Speed.

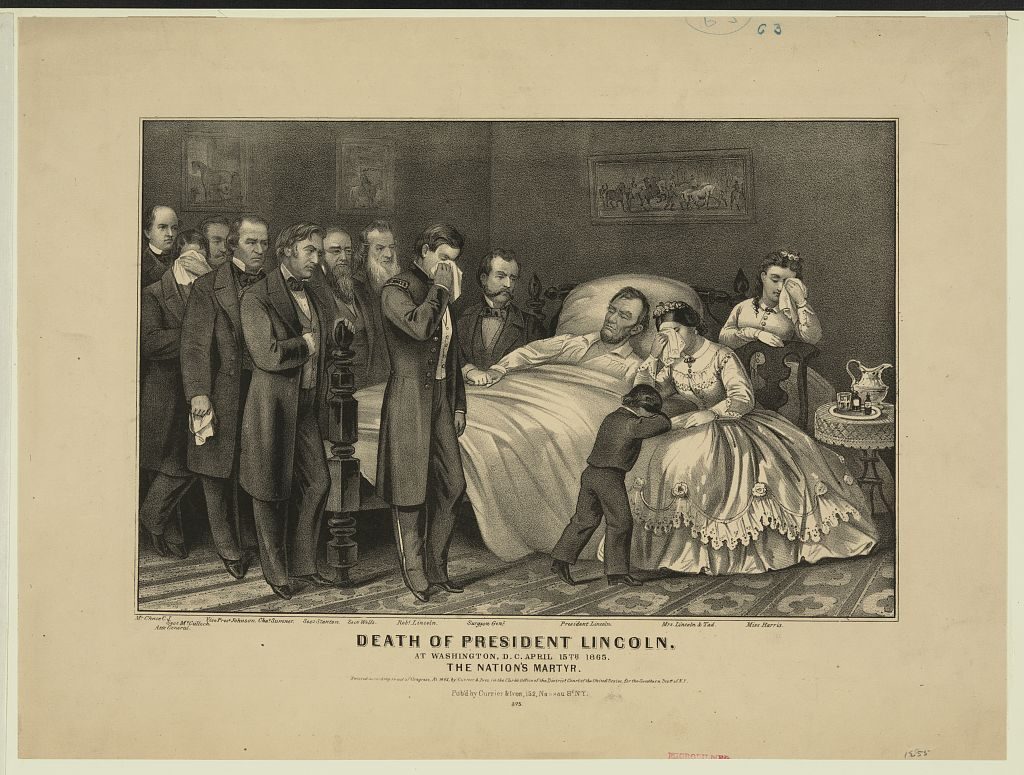

Currier and Ives’s took their 1865 print a step farther, including the words “The Nation’s Martyr” in their title. They positioned Mary Lincoln and the boys as part of the central focus while the politicians take a more side role, though they named and identified all figures in this print.

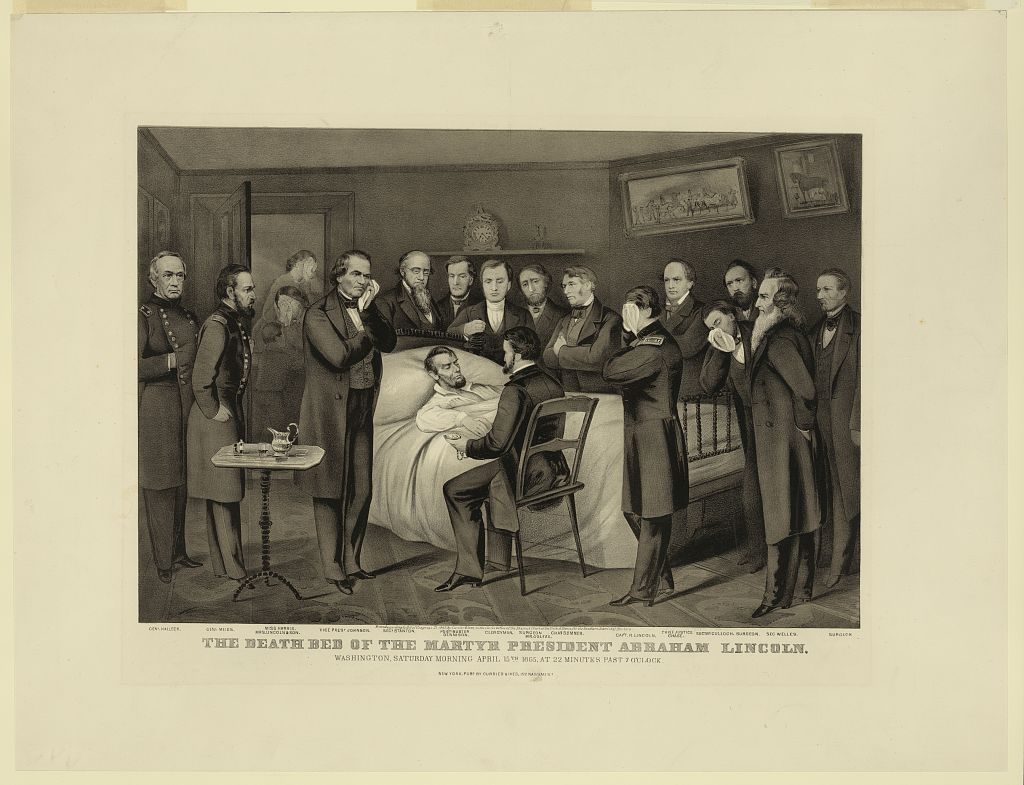

A second 1865 print by Currier and Ives. Notice how in this illustration Mrs. Lincoln has been pushed to the doorway and the male leaders take the roles of mourners. Andrew Johnson stands prominently beside Lincoln’s bedside, and the figures are labeled in the artwork.

E.B. and E.C. Kellogg attempted to show another angle of the scene in their 1865 print. Varying from other illustrator’s side view, they opted for a straight-on view of the dying president and clustered the politicians and other leaders around. Mary Lincoln makes no appearance here, but Tad Lincoln watches at the foot of the bed. They also labeled the political leaders in their scene.

In 1875, artist Alexander Hay Ritchie created this depiction for popular art prints. Following the tradition of other artists in many ways, Ritchie made a significant change. There are no women in this version. Mary Lincoln does not grieve. It is almost a scene of politics around the dying president’s bedside.

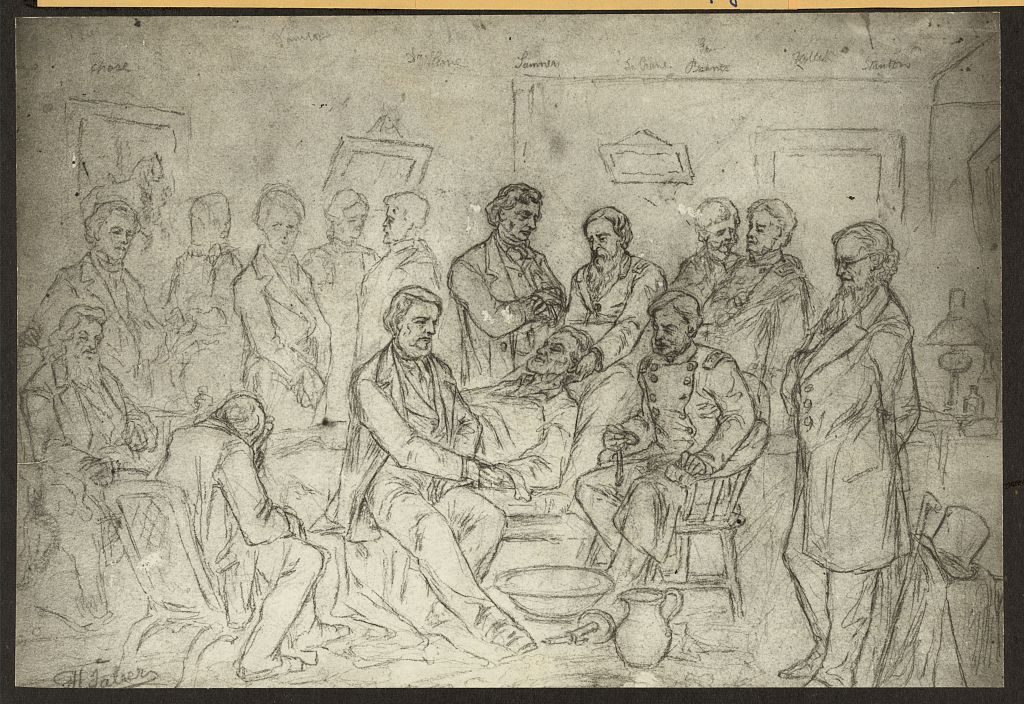

Do we have any “real time” images of the scene that night and morning? Yes. Artist Alfred Waud made some sketches, but some of the most significant were drawn by Hermann Faber.

In contrast to the prints, Hermann Faber created two sketches of the room before the doctors sent all non-essential persons from the chamber. Faber – an artist serving on the Surgeon General’s staff and already familiar with creating illustrated medical records – offers a glimpse into the scene.

Notice the surgeon holding up the president and bandaging his head. Political leaders look on, and Mary Lincoln is absent while her husband is undergoing medical care.

The second of Faber’s sketches depicts the medical men still attending while more cabinet members and other leaders have arrived. Note the timepiece in the seated man’s hand, probably to measuring the president’s pulse.

The artistic prints clearly reflect a historical reality, but the real time sketches seem to offer the most valuable insight. Later, artists would add political leaders and the Lincoln family to their scenes as they wanted, not always careful of historical facts.

Political leaders entered and exited that night. Dr. Leale, Gideon Welles, Edwin Stanton, Dr. Robert S. King, and Charles Sumner stayed through the long hours. Mary Lincoln came and departed as she went through varying stages of confession and grief. Robert Lincoln did arrive at his father’s deathbed, but Tad Lincoln stayed at the White House, inconsolable in his grief and finally put to bed by one of the staff.

Looking at these prints and sketches, we can take away several observations of the facts and later opinionated perspective on the scene of President Lincoln’s deathbed:

- The event and scene captured the American mind. Perhaps this scene came to represent the thousands of unrecorded and unillustrated deaths that had occurred in the last four years.

- Lincoln’s deathbed in reality and depiction evoked the old ideas of “good death” along with the battlefield changes. Lincoln died in a bed, surrounded by grieving family and friends – but he also died of a wound.

- The artistic interpretations became a tool of imagery and borderline propaganda – depending on the presence, position, and attitude of political figures and/or Lincoln’s family members.

Perhaps final stanza from Walt Whitman’s poem O Captain! My Captain verbally reflects the scene in the Peterson House on April 15 which visual illustrators tried to record. Lincoln’s death signaled a new period of political and national turmoil, but for the mourners it was an intensely personal moment.

My Captain does not answer, his lips are pale and still,

My father does not feel my arm, he has no pulse nor will,

The ship is anchor’d safe and sound, its voyage closed and done,

From fearful trip the victor ship comes in with object won;

Exult O shores, and ring O bells!

But I with mournful tread,

Walk the deck my Captain lies,

Fallen cold and dead.

I often think about Tad Lincoln.How on earth did he cope with his life? His father must have given him such strength and such a positive view of the world. Tad endured many deaths in his short lifetime. He saw national mourning for Elmer Ellsworth as well as his father. Both boys were deeply affected by the deaths of those they had known–Edward Baker comes to mind. Then he lost his brother while he survived. He was at another play when his father was shot–survivor’s guilt? I think he was simply an amazingly strong person, even though he was so young. It makes sense that he stayed with his mother intil his own death at eighteen.

“Pa is dead. I can hardly believe that I shall never see him again. I must learn to take care of myself now. Yes, Pa is dead, and I am only Tad Lincoln now, little Tad, like other little boys. I am not a president’s son now. I won’t have many presents anymore. Well, I will try and be a good boy, and will hope to go someday to Pa and brother Willie, in Heaven.”

from “All the President’s Children” by Doug Weed

Yes, I was reading about Tad while working on this article. So sad (please send handkerchiefs). I just couldn’t find a way to work it into the article this time, so I appreciate you adding it to the comments.

This article may interest you…rogerjnorton.com/tadfile.pdf..