A Visit to the Site of the Final Surrender

To reach the site of the last Confederate surrender, I first have to cross a cemetery. Along the back wall, three brick stairs offer access to a gravel pathway that leads off into the woods and the 35-acre Doaksville archaeological site. However, recent rains have flooded across this cemetery, funneling down the back slope and washing away part of the brick wall. In my cowboy boots, with their smooth soles, I have to pick my way careful across the soggy mess. Otherwise, I’ll slip and slide down the bank, too.

To reach the site of the last Confederate surrender, I first have to cross a cemetery. Along the back wall, three brick stairs offer access to a gravel pathway that leads off into the woods and the 35-acre Doaksville archaeological site. However, recent rains have flooded across this cemetery, funneling down the back slope and washing away part of the brick wall. In my cowboy boots, with their smooth soles, I have to pick my way careful across the soggy mess. Otherwise, I’ll slip and slide down the bank, too.

I make it to the stairs and then up and over. Along the waiting path, fourteen interpretive panels explain the history of the former trading community–once the largest in all of Indian Territory. Today, nothing remains of Doaksville except for a number of stone wells, all capped, that dot the landscape like checkers that have all been kinged. A few stone foundations hunker next to the path and behind trees. In an old stone jail, the outline of the three jail cells remains clearly visible, even if now completely impotent with no walls or bars.

The 3/4-mile trail makes a topsy-turvy loop the way a go-kart track might twist back-and-forth and go up and down small rises before bringing you back to the start. I’m the only one out here, so there’ll be no racing.

The place feels abandoned, which is no surprise because that’s literally what happened to it. When the railroad came through this part of Oklahoma, it bypassed Doaksville in favor of Fort Towson just a couple miles to the south. That, in effect, killed the village. As a historic site, Doaksville falls under the purview of the Oklahoma Historic Society, which takes care of the place.

I have driven up from Dallas, by way of Paris, Texas. I crossed the Red River—flowing high from the recent rains and brownish red from the subsequent run-off—and passed through the Choctaw reservation. I expected things to be more, well, dusty, I guess, but the state is beautiful: rolling grasslands punctuated by stands of forests. The Dust Bowl, whatever its power of impression on me, has been long gone.

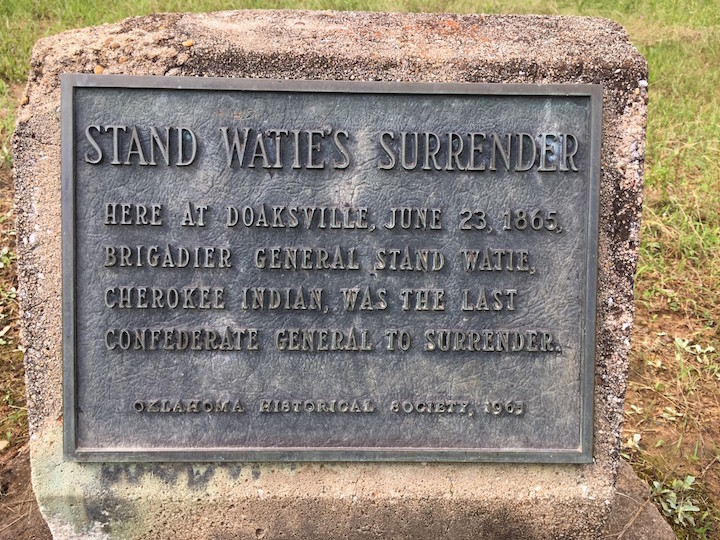

The Doaksville archaeological sites sits one mile north of the modern town of Fort Towson. Here, on June 23, 1865, confederate Brigadier General Stand Watie surrendered his troops to Lieutenant Colonel Asa C. Matthews and his Federal troops from the historical Fort Towson. There seems to be no exact tally of the number of men serving under Watie at the time of their surrender, only that he led a mixed band of Creek, Seminole, Cherokee, and Osage Indians. Theirs was the last surrender of Confederate troops in the war.

The Doaksville archaeological sites sits one mile north of the modern town of Fort Towson. Here, on June 23, 1865, confederate Brigadier General Stand Watie surrendered his troops to Lieutenant Colonel Asa C. Matthews and his Federal troops from the historical Fort Towson. There seems to be no exact tally of the number of men serving under Watie at the time of their surrender, only that he led a mixed band of Creek, Seminole, Cherokee, and Osage Indians. Theirs was the last surrender of Confederate troops in the war.

It wasn’t as though Watie had been holding out to some bitter end. News from the east just hadn’t reached this far until well into June. As late as April 24, Federal cavalry intercepted a Confederate mail bag that made it clear no one knew yet about Lee’s April 9 surrender at Appomattox or Joe Johnston’s April 18 surrender at Bennett Place.

General Edmund Kirby Smith surrendered Confederate troops of the Trans-Mississippi on June 2 at a ceremony in Galveston, Texas. It took three weeks for word to make its way north from there to Indian territory where Watie and his force had been operating in the war’s late months more as partisan rangers than as a formal military force.

Beyond that, I know a little about the Civil War in Indian territory. I know most of the Indian nations sided with the Confederacy, which offered them far more generous treaty terms than United States government.

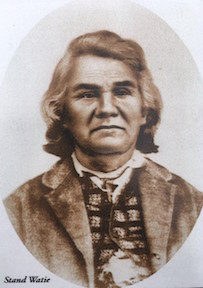

Watie, born Degataga, which meant “Stand Firm,” was a mixed-blood Cherokee who had controversially supported Indian removal from Georgia in the 1930s. He led the earliest push for Confederate allegiance, even raising a unit, the 1st Cherokee Mounted Infantry, before his nation even declared an allegiance. Cherokee leader John Ross had initially urged neutrality, but soon, he and the Cherokee followed Watie’s lead and cast their lot with the South. It would be a fickle alliance, though, and by August of 1862, Ross and a majority of the Cherokee switched sides, although Watie remained loyal to the Confederacy to the end.

Watie, born Degataga, which meant “Stand Firm,” was a mixed-blood Cherokee who had controversially supported Indian removal from Georgia in the 1930s. He led the earliest push for Confederate allegiance, even raising a unit, the 1st Cherokee Mounted Infantry, before his nation even declared an allegiance. Cherokee leader John Ross had initially urged neutrality, but soon, he and the Cherokee followed Watie’s lead and cast their lot with the South. It would be a fickle alliance, though, and by August of 1862, Ross and a majority of the Cherokee switched sides, although Watie remained loyal to the Confederacy to the end.

Watie participated in a number of engagements in the Trans-Missisippi Theatre, mostly in Indian Territory, although he notably took part in the fight at Pea Ridge, Arkansas, and Wilson’s Creek, Missouri. On May 10, 1864, he earned his promotion to brigadier general. He became, by far, the most famous Native American figure from the war (although, as someone who comes from Western New York, home of the Seneca nation of Indians, I’ve always been partial to Eli Parker of U.S. Grant’s staff).

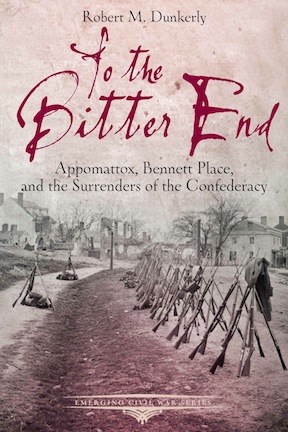

My interest in coming to Doaksville, though, has less to do with Watie himself than its standing as a surrender site. Bert Dunkerly’s excellent ECWS book To the Bitter End recounts the slow unraveling of the Confederacy, which began with formal precision at Appomattox and progressed in increasingly disjointed fashion over subsequent months. Watie’s surrender was as much a final loose end on a long tattered strand then anything else, so it’s a little wonder that it’s little remembered. But it was the final military surrender, nonetheless, and so piqued my curiosity and desire to see it for myself.

My interest in coming to Doaksville, though, has less to do with Watie himself than its standing as a surrender site. Bert Dunkerly’s excellent ECWS book To the Bitter End recounts the slow unraveling of the Confederacy, which began with formal precision at Appomattox and progressed in increasingly disjointed fashion over subsequent months. Watie’s surrender was as much a final loose end on a long tattered strand then anything else, so it’s a little wonder that it’s little remembered. But it was the final military surrender, nonetheless, and so piqued my curiosity and desire to see it for myself.

One of the Doaksville trail’s waysides, explaining the surrender, stands next to two small monuments no taller than my knees. On one, a plaque offers a few sentences commemorating the existence of Doaksville; the other commemorates Watie’s surrender. Juxtaposed against the expansive park at Appomattox, and the well-manicured site at Bennett Place, these two markers on the edge of a clearing of overgrown grasses has a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it feel.

My boots crunch in the gravel as I finish the loop and head back to the stairs that will take me to the cemetery and across the sopping slick grass to my car. I leave satisfied that I’ve checked off a site I’ve long wanted to see, but I also leave with more questions than answers, with more things to investigate and learn. Doaksville, it seems, is not so forgotten after all.

Chris, first of all the Hershey Civil War Roundtable wants to Thank You for presenting The Battle of the Wilderness to our group. Everyone is still talking about your excellent talk and looking forward to the Field Trip this fall.

My Family is from Oklahoma and during one of my visits to Oklahoma,I went to this surrender site. It is out of the way, but am important and interesting place to visit.

In one of the final episodes of Ken Burn’s excellent series, The Civil War, it is stated, “Palmito Ranch, fought in May 1865 in Texas was the last battle of the Civil War. It was a Confederate victory.” This, and the above recognition of Stand Watie, serves to indicate the War of the Rebellion was not neat and tidy, neither “beginning” out of the blue on 12 April 1861, nor ending April 9th 1865 …constructs developed for the “only complete as necessary” instruction of children’s history in primary school. The full story is much more complex and interesting, don’t you think?

To complete this picture, folks, note that the list of Stand Watie’s forces did not include Choctaw. The Choctaw forces, under Principal Chief Peter Pitchlynn, surrendered separately at Doaksville on the same day. (Pitchlynn was not subordinate to Watie, incidentally.) It is also important to recognize that Doaksville was the capital of the Choctaw Nation 1860-1863.