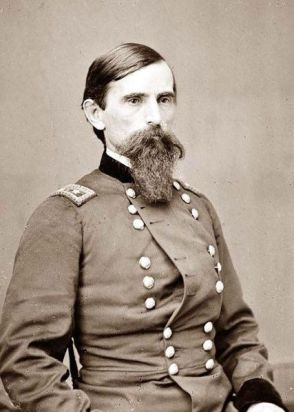

Lew Wallace Secures the B&O– For the First Time (Pt. 2)

It was a busy June for Lew Wallace. He and his 11th Indiana Zouaves had been posted at Cumberland, Maryland to guard the vital Baltimore & Ohio Railroad bridges across the Potomac River.

Their raid against Romney, Virginia had elicited a Confederate response, and now, by late June, 1861, it seemed like the Hoosiers were on their own. Wallace feared the worst– a Confederate attack directly against Cumberland, and made plans to keep his retreat open into Pennsylvania, just ten miles away.

The Unionists of Cumberland came together to help Wallace’s men. In his autobiography, Wallace wrote that the town provided his troops with fresh food, ammunition, and even tobacco when there was a “famine” of the latter’s availability.[1]

While the Cumberlanders were helping Wallace, others in the area annoyed him to no end. On June 21, two regiments of infantry and a battery of artillery from the Pennsylvania Reserve Corps received orders to leave Harrisburg and head for the Pennsylvania-Maryland border. While the Pennsylvanians were sent to help Wallace, the state’s governor Andrew Curtin gave the expedition’s commander, Col. Charles Biddle, puzzling instructions that Biddle was not to go past the state line. Wallace called the situation “ludicrous” and prevented him from going back on the offensive.[2]

The Pennsylvanians were out of sorts because of their orders, too. Eagerly leaving for the front, the soldiers established Camp Mason & Dixon, but soon changed the name sarcastically to Camp “Misery and Death,” as one Pennsylvanian explained, “on account of the sickness which prevailed, and scarcity of rations.”[3] Others were frustrated by their governor’s orders that hamstrung them and left them unavailable to cross into Maryland and join Wallace’s force. Riding towards their camp, Wallace remembered that Lt. Charles Campbell, in command of the Pennsylvanians’ artillery, “had not taken kindly to the restraining order.” Campbell’s guns were “extended over what he energetically denominated, ‘the damned state line.’”[4]

With the Pennsylvanians of no use for the time being, Wallace still had to make plans in case the Confederates attacked his positions. With only his Zouaves at hand, Wallace needed to think outside the box. He sent soldiers into the countryside to gather as many horses as they could, which disappointingly came to be only thirteen mounts. The horses, Wallace wrote, “were pretty fair, but would have been condemned by a government inspector.”[5] Picking thirteen soldiers, Wallace chose Cpl. David B. Hay to lead them. Hay was described by another as, “a soldier in the Mexican War and was a fighter and a daredevil from away back.”[6]

Hay and his fellow soldiers were to scout the area, and bring any intelligence back to Wallace. They began daily patrols into the countryside around Cumberland, trying to see if there were Confederates threatening Wallace’s location. On June 26, Hay had his greatest test outside of Cumberland.

The Hoosiers were riding south, heading for a small town called Frankfort, lying halfway between Cumberland and Romney. As Hay’s riders approached the town, they “found it full of cavalry.” Clearly outnumbered, the Indianans turned around and began to retrace their steps. Confederate troopers, spotting them, spurred after the Federals.[7]

Hay’s scouts made good time and soon evaded their pursuers. Behind them, the Confederates split up and continued their search. One party of riders, about seven men, were led by Capt. Richard Ashby, the younger brother of cavalier Turner Ashby. Richard Ashby led his troopers forward, trying to find their Federal prey.[8]

The Hoosiers found the Virginians first, though. Hay’s men lay in wait, and when Ashby’s men came into view, the Indianans opened fire with their rifles. In the melee that followed, David Hay received a sword slash and two pistol wounds, and Richard Ashby, unhorsed by his buckling horse, was shot and subsequently stabbed in the abdomen with a bayonet. He died seven days later. The Virginian cavalry broke for Romney, and Federals made their back towards Cumberland. Two of the Hoosiers rode ahead, searching for a wagon to put the wounded Hay into.[9]

As they made their retreat, Hay’s mounted infantry came to Kelley’s Island, situated to the east of Cumberland on the Potomac River. It had brush and large pieces of driftwood that offered the Federals a chance for cover and concealment. And the soldiers would need it, because on their heels was Richard’s brother, Turner, who rode hell bent for leather to the sound of the firing.[10]

Captain Turner Ashby rode at the head of a dozen Virginian troopers. He came to the edge of the water facing Kelley’s Island, and seeing the Federals, cried out, “Charge them, men, and at them with your bowie knives!” The river, about thirty or forty-five yards wide at that point, slowed the cavalry charge as the horses and riders galloped into the water.[11]

Hay’s Indianans opened fire. Two Virginians were killed, and Ashby was wounded, his horse killed. As the Virginians finished their wild charge, the two forces closed in on each other. The Hoosiers carried their rifles and sword bayonets, which Wallace wrote were “fairly good for hand-to-hand encounter.”[12]

What followed was a furious melee that pitted both sides in what amounted to a running fight as the Federals made brief stands among the rocks. Both sides came to wildly overstate the losses they inflicted on each other; a Zouave reported they had killed “thirty-one of the rebels” while a Confederate, reporting the Federal strength to be about forty, claimed the Unionists had “eight or ten killed.” Remember though, in the skirmish at Kelley’s Island, both sides had about a dozen soldiers. The losses appear more likely, on both sides, to be counted in the single digits.[13]

Darkness and the arrival of Hoosier reinforcements brought an end to the fight. The two Indianans who had been sent ahead to find a wagon, hearing the gunfire at Kelley’s Island, instead spurred for Cumberland. They reported to Wallace, who turned out two companies of the 11th Indiana to march to the island. Those companies arrived to find the skirmish already over. Hays’ scouts had fled under the growing darkness, and Turner Ashby brought his squad’s worth of troopers back across the river into Virginia.[14]

On June 27 the 11th Indiana went out again towards the island, and brought back the only Federal fatality from the day before, Pvt. John C. Hollenbeck. They buried him in a funeral that involved the whole regiment and “Honors of War.” A witness wrote “It was very impressive.” Wallace recommended Cpl. Hay, who recovered from his wounds, receive a promotion to second lieutenant.[15]

The dual cavalry skirmishes on June 26, involving just small parties of mounted men on both sides, had caused more casualties than Wallace’s strike on Romney with his entire regiment. But those fights, seen as victories for the 11th Indiana, garnered their colonel praise from all directions. His commanding officer, Maj. Gen. Robert Patterson, issued congratulatory orders that praised the conduct of the 11th. Maj. Gen. George McClellan and U.S. Congressman Schuyler Colfax both personally wrote to Wallace to offer their congratulations.[16]

In the space of sixteen days since his arrival at Cumberland, Wallace’s raid against Romney and his scouts’ cavalry skirmishes had brought the war front and center for the people living there. He continued his objective of guarding the Baltimore & Ohio, and now it remained to be seen if there was to be any more fighting along the tracks.

_____________________________________________________________

[1] Lew Wallace, An Autobiography, Vol. 1 (Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1905),294.

[2] Ibid., 296.

[3] John Bard, History of the Old Bucktails (Clearfield County Historical Society, 2013), 5.

[4] Wallace, 296.

[5] Ibid., 293.

[6] Thomas W. Durham, Three Years with Wallace’s Zouaves: The Civil War Memoirs of Thomas Wise Durham, ed. Jeffrey L. Patrick (Macon: Mercer University Press, 2003), 40.

[7] Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies in the War of the Rebellion (OR) Ser. 1, Vol. 2,134.

[8] Frank Moore, ed., The Rebellion Record: A Diary of American Events, Vol. 2 (New York: G.P. Putnam, 1864), 242.

[9]James B. Avirett, The Memoirs of General Turner Ashby and His Compeers (Baltimore: Selby & Dulany, 1867), 110; OR, Ser. 1, Vol. 2, 134-135; Durham, 41; Gail Stephens, Shadow of Shiloh: Major General Lew Wallace in the Civil War (Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society, 2010), 28.

[10] Durham, 41; Paul C. Anderson, Blood Image: Turner Ashby in the Southern Mind (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 2002), 81; Wallace, 302.

[11] Avirett, 111; Anderson, 81.

[12] Clarence Thomas, General Turner Ashby: The Centaur of the South (Winchester: Eddy Press Corporation, 1907), 30; Moore, 242; Wallace, 298.

[13] Durham, 41; Moore, 242.

[14] Wallace, Auto, 304.

[15] Durham, 42; Wallace, 305.

[16] Wallace, 305-307.

A rousing tale- thank you !