Stout Hearts: Attempting to Feed Both Civilians and Soldiers

ECW welcomes Katie Brown to share Part 2 of her research. (Find Part 1 here)

“The provision blockade is nothing; we shall have wheat, corn, and beef beyond measure…,” Sergeant S.R. Cockrill of Tennessee assured a friend in June 1861, “Fear nothing, success is certain.” [1]

Despite what we know today about hunger’s prevalence in the Civil War, there was initially some disagreement over the dangers of famine and starvation. “The South can never sustain this contest for any length of time,” The Vermont Phoenix reported in April 1861, directly contradicting Cockrill’s opinion. “Their enemies are not Northern troops alone; but the harder hearted foes, hunger, want of money, and slaves watching for an opportunity to apply the torch to Southern homes.”[2]

Despite some Southerner’s optimism, hunger soon became a recognized problem among leadership on both sides of the conflict. The Confederate government faced a problem in balancing the hunger of civilians versus soldiers. Despite their different situation occupying enemy territory, Northern leaders faced similar questions in Union-held areas.

Although soldiers were usually deemed a priority for food and resources, many soldiers went hungry. Leaders believed that, as young men, soldiers were more able to bear hunger than the women, children, and elderly that they had left at home. Rather than sending a request for food up the chain of command, many leaders instead implored the soldiers to face it “in a cheerful, manly spirit.”[3] Prior to an expedition far from his supply lines in April 1864, Union cavalry commander William Averell issued a general order, calling upon his men’s “soldierly qualities” to endure. “Hunger and fatigue will be your greatest enemies,” he wrote, “let them be met with stout hearts.”[4]

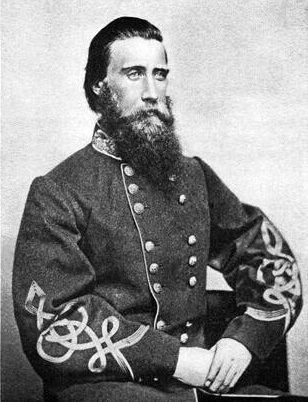

Some generals even presented hunger as a patriotic opportunity. “The fruitful fields of Tennessee are before us,” Confederate General John Bell Hood wrote to his men in November 1864, “and as we march to repossess them, let us remember that the country we traverse, perhaps with hunger, was a rich and bountiful land till wasted by the enemy, that similar desolation awaits every portion of our country relinquished to the invader, and let the privation be to us not a cause of murmuring, but an incentive and an occasion for the exhibition of a most determined patriotism.”[5] As General Hood implied, soldiers faced hunger because it was a part of their manly and patriotic duty to protect the civilians left on the homefront.

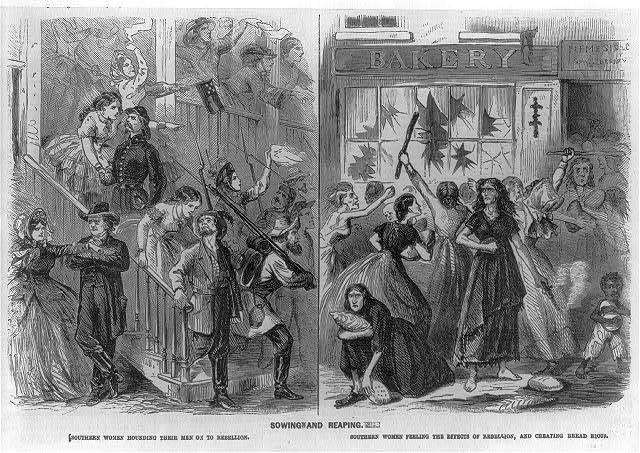

Initially, these civilians were not expected to face hunger the same way. While fasting days and “starvation parties” practiced by civilians of the Confederacy during the war show a similar recognition of the relationship between hunger and patriotism, leaders on both sides wrote countless letters and reports worrying about the hunger they saw among civilians across the South. These letters strike a different chord from those referring to the hunger of soldiers, particularly in their use of the word “starvation.”[6]

While no solid evidence exists of people in conflicted areas dying of starvation (other than prisoners of war who are a special case), both the leaders and civilians of the era believed this was a distinct possibility. As one man named John Tyler (but who was not the former president) wrote from Petersburg, Virginia, in July 1864, “All things taken together, our mere military status is good, but how my heart sinks within me at the inevitable suffering of our people through actual want and starvation… This I fear more than the muskets and cannon of the enemy.”[7] Another community in Alabama petitioned Confederate President Jefferson Davis on the grounds that they were starving, arguing that “Deaths from starvation have absolutely occurred, notwithstanding the utmost efforts that we have been able to make, and now many of the women and children are seeking and feeding upon bran from the mills.”[8]

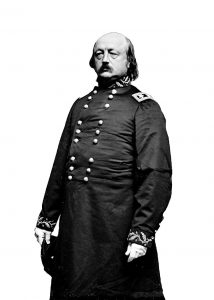

Faced with starving civilians, leaders of both sides set up welfare programs that would redistribute provisions. In Virginia, such efforts originally began at the local level as a means of supporting soldiers’ families; however, this was not always enough, and the state government began to step in to assist.[9] In Union-held areas, the responsibility of feeding civilians fell to the United States Government. Union forces were particularly startled by the hunger they found within New Orleans, which had been cut off from supplies for months. Union General Benjamin Butler dedicated many reports to this issue, writing that “the condition of the people here is a very alarming one. They have literally come down to starvation… I am distributing in various ways about $50,000 per month in food and more is needed.”[10] General Ulysses Grant maintained a similar approach to charity in Mississippi in December 1862, issuing Special Field Orders Number 21. The army had wrought destruction in the area and therefore should provide for the civilians who had been affected, he argued, for “…in a land of plenty no one should suffer the pangs of hunger.”[11]

This dedication to sparing the stomachs of civilians faded over time, however, and by the end of the war and even afterwards, hunger had become a weapon unto itself. In a letter demanding the surrender of Savannah, Georgia, General William Sherman wrote “Should I be forced to resort to assault, and the slower and surer process of starvation, I shall then feel justified in resorting to the harshest measures…”[12] Even Benjamin Butler changed his tune throughout and after the war, expressing a lack of concern for the starvation of civilians that was a far cry from his reports of New Orleans; in response to a proposal in 1867 to feed hungry Southerners using money from the Freedman’s Bureau, Butler responded: “The men and women who stood by and viewed without compassion the miseries endured by our noble soldiers will, if they experience a little starvation, themselves, be able to realize what was suffered in Southern prisons by those who fought our battles.”[13]

Leaders’ responses – like Butler’s – throughout the war to feeding civilians and soldiers was ultimately shaped by their belief in the importance of paternalism and their view of civilians (a term which largely referred to women, children, and the elderly) as helpless and vulnerable. As men, soldiers were believed to be more able to face the privations of warfare, such as hunger, and therefore were perceived as willing to sacrifice for the good of those still back at home. This expectation reflects the social structures of gender, class, and charity of the time, where wealthy men were responsible for the health and success of their households and communities and the helpless left at home could do nothing but wait for assistance.[14] Statements like Butler’s also reveal accusations of barbarity, where the starvation of civilians was seen as someone’s fault for not protecting and providing for those who could not defend themselves (another topic for another day). What these leaders’ observations do not tell us, however, is the reality of individual experiences of hunger, the impact that food shortages had on a personal level… and the disintegration of social mores that followed.

To be continued…

———-

Katie Brown is an emerging historian and freelance writer who graduated with her Master’s in History in 2018 and has since worked as the Program Coordinator for the Virginia Center for Civil War Studies at Virginia Tech. She believes in the power of history to teach a better understanding of the human experience and strives to write and teach history that is relevant to all.

Sources:

[1] S.R. Cockrill to [William S.] Walker, June 21, 1861, The War of the Rebellion, Official Records of the Civil War (OR), ser. 1, vol. 52, pt. 2, 114.

[2] “Local Intelligence,” The Vermont Phoenix, April 25, 1861.

[3] John Bell Hood, “General Field Orders, No. 35, November 20, 1864,” OR, ser. 1, vol. 45, pt. 1, 1227.

[4] William W. Averell, “General Orders, No. 1, May 1, 1864” OR, ser. 1, vol. 37, pt. 1, 365.

[5] Hood, “General Field Orders, No. 35.”

[6] In this case, civilian usually refers to the white residents of an area. There are dimensions of race to this study that are not explored here.

[7] John Tyler to Sterling Price, July 9, 1864, OR, ser. 1, vol. 40, pt. 3, 759.

[8] Citizens of Randolph County to Jefferson Davis, May 6, 1864, OR, ser. 1. Vol. 52, pt. 2, 667. This letter was written as a plea to Jefferson Davis to return the slaves that had been impressed by the Confederate army; as a result, it is possible that the letter’s assertion of starvation is an exaggeration. The citizens may have been presenting themselves as more helpless than they actually were in order to convince the president that their needs were greater than those of the army.

[9] William Blair, Virginia’s Private War: Feeding Body and Soul in the Confederacy, 1861-1865 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998), 75.

[10] Benjamin F. Butler to Henry W. Halleck, September 1, 1862. In Jessie Ames Marshall, Private and Official Correspondence of Gen. Benjamin F. Butler, Volume II (Norwood, MA: The Plimpton Press, 1917), 242.

[11] Ulysses Grant, “Special Field Order, No. 21, December 12, 1862,” OR, ser. 1, vol. 17, pt. 2, 405.

[12] William Sherman to William Hardee, December 17, 1864, OR, ser. 1, vol. 44, 737.

[13] “Southern Relief Bill,” New York Tribune, March 14, 1867. In Judith Giesberg, “The Fortieth Congress, Southern Women, and the Gender Politics of Postwar Occupation,” in Occupied Women: Gender and Military Occupation and the American Civil War, ed. LeeAnn Whites and Alecia P. Long (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2009), 185.

[14] Aaron Sheehan-Dean, Why Confederates Fought: Family & Nation in Civil War Virginia (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007), 116. As Sheehan-Dean writes, the local model of charity adopted by the state of Virginia and military leaders in places like New Orleans reflected antebellum expectations of charity.

Interesting subject- thanks.