“Down Fame’s Ladder”: Brigadier General Thomas W. Egan’s Unending War

Major General Winfield Scott Hancock gave glowing praise of the Third Division’s 1st Brigade and its commander, 29-year-old Colonel Thomas W. Egan, in his report following the Battle of North Anna on May 23, 1864. “Egan’s brigade, led gallantly by its commander, charged over an open field, several hundred yards in breadth, which ascended sharply towards the enemy’s position, carrying the intrenchments, and driving the enemy pell-mell across the stream, with considerable loss to them,” Hancock wrote. The Gettysburg hero had witnessed numerous acts of gallantry during the war, but the seizure of the Confederate entrenchments and strategically important Chesterfield Bridge was unlike anything he had seen before. “I have seldom witnessed such gallantry and spirit as the brigade of Egan displayed in the assault upon the enemy’s works which covered the wooden bridge over the North Anna.”[1]

This was not the first instance during the war that Egan had been commended for his resourcefulness and bravery in battle. Colonel “Fighting Tom” Egan had been impressing his superiors dating back to the summer of 1862. During General McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign, he led the 40th New York Infantry Regiment at Glendale, Malvern Hill, and Fair Oaks, where he was wounded in the left side of his head. He attracted the notice of his division commander, Major General Philip Kearny, who declared he was “one of his best fighting colonels.”

In December 1862, Major General John Pope petitioned the authorities in Washington for Egan’s promotion to general. “Colonel Egan was regarded by General Kearny as one of his most distinguished and capable officers, and he deserves and should receive promotion,” Pope reasoned. “It will be well for the interests of the Government, as well as proper tribute of gratitude from the Government, that Colonel Egan should be appointed brigadier-general.” Other Union generals, including John H. Hobart Ward, David B. Birney, Fitz John Porter, Hiram G. Berry, John Sedgwick, Samuel P. Heintzelman, Joseph Hooker, Daniel E. Sickles, and John C. Robinson, had equally good things to say about the fighting colonel of the 40th.[2]

Following solid performances at Second Bull Run, Chantilly, and Chancellorsville, Egan led his regiment to Gettysburg as part of Major General Daniel E. Sickles’s Third Corps in July 1863. During the fighting near Devil’s Den, he had two horses killed from under him and was shot in the middle of the right thigh. Captain James E. Smith of the Fourth New York Battery was enamored by the New Yorker’s heroics on that hot July afternoon. “If the American people had seen this fearless soldier in the battle at ‘Devil’s Den,’ July 2, 1863,” Smith praised of Egan, “his name would be a household word at every fireside…”[3]

During the Second Battle of Petersburg on June 16, 1864, two days before his thirtieth birthday, Egan toppled from his horse with wound number three. A shell fragment penetrated his back one inch to the left of his spine. The wound threatened to leave him paralyzed from the waist down. For two months he could hardly move.[4]

General Hancock, who was nearby when Egan was severely wounded, pressed for his promotion in early September. Inspector-General James A. Hardie, inquiring into the matter, telegraphed Grant on September 2, 1864: “[T]here is an application before the department of the appointment of Colonel T.W. Egan, 40th New-York Cols to be a Brigadier General. The testimonies are numerous. The President’s [sic] thinks it a strong case. Shall the appointment be made?” Lt. Colonel Theodore S. Bowers, assistant adjutant-general to Grant, telegraphed Hancock and asked to know if he desired Egan’s promotion in advance of others deserving II Corps officers. “Col Egan is entitled to promotion,” Hancock replied the same day. “He was the first on my list made sometime since of those officers who commanded troops.”[5]

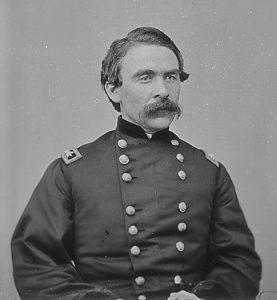

Egan received his promotion to brigadier general on September 3, 1864. Before war’s end, he suffered a fourth wound when a musket ball pierced his right forearm and fractured his ulna. Fighting Tom ended the war as a brevet major general.

Egan returned to New York a physical wreck. For two years after suffering these wounds, he was under the constant care of nurses and physicians. He suffered from lingering paralysis to his lower limbs and his right arm was virtually useless. He experienced regular stiffness and shooting pain to his right leg, indicating severe nerve damage. During wet or damp weather, Egan was unable to move at all. Bone fragments continued to be exfoliated from his right arm. He struggled to lift his right forearm and hand. He could hardly grasp a pencil to write. By 1873, a doctor who examined him reported, “Disability total; permanent.”[6]

If his disability was not distressing enough, Tom Egan had marital problems. He divorced his wife, a beautiful blonde New York stage actress named Marie Gordon. Mr. and Mrs. Egan had been on the rocks for some time, but the divorce was not finalized until 1866. It is quite possible that Tom’s poor health strained their relationship, but infidelity was the root cause of the breakup. He discovered Marie in bed with a friend. Luckily, Marie managed to dissuade Tom from beating her lover to death. She remarried after the divorce and left for London in 1867, taking with her Tom’s only son.[7]

The war hero began to frequent saloons to find relief from his broken health and financial and marital problems. Drinking may have also helped him to cope with the psychological trauma he experienced as a result of his wartime service. In September 1882, a man released from an insane asylum, William H. Westbrook, was arrested for striking Egan in the face during a quarrel in a saloon over forty cents. In July 1883, Egan pawned a gold-headed cane to a pawnbroker named Lewis Myers for ten cents. When Egan attempted to pay back the ten cents and redeem the cane, Myers told him that he owed twenty cents more. When Marshal George A. McDermott intervened, he sided with pawnbroker. Egan could not produce the receipt, but Myers was able to present the paperwork showing that Egan had in fact been loaned thirty cents. Egan protested to Mayor Franklin Edson that he had been unfairly treated by McDermott, but his grievance fell on deaf ears.[8]

A year after this incident, Egan was arrested for public intoxication. In early July 1884, he was brought before Justice Solon B. Smith to stand trial. The two had been on a first-name basis at one time in their lives – they referred to each other as Tom and Sol during the trial. But Sol recognized that the shabby-looking man standing before him was no longer the Tom he had once known, but simply a “miserable drunken tramp.” Even worse, Egan acted strangely during the trial, at one point making the outlandish assertion that he was worth $40,000,000. His odd behavior did not help his case.

“Drinking has somewhat unbalanced your mind and I’ll change the complaint against you into insanity,” Smith declared. The judge ordered Egan sent to an insane asylum. The court officer, a veteran who had served under Egan during the war, could not bear to bring himself to escort the general from the courtroom and had to ask the judge to be excused from the task.[9]

Those that knew Egan during the war – a man praised by Hancock, Kearny, and even Lincoln – could not wrap their minds around how a soldier of such merit ended up in such a shameful condition. Newspapers, once exalting him for his bravery during the war, now claimed he was “hopelessly insane.” One newspaper correspondent recalled having bumped into Egan on the street and was shocked by what he found. “[H]e was walking along Printing House Square, old and bent, though he is really no more than 48 or 50, and so seedy that I took him for a tramp,” the man reported. The general broke down into tears when this old acquaintance passed by without even recognizing him. “I think, that if I had been told, when I used to see Eagan [Egan] galloping around camp surrounded by his staff, that he would one day be sent to the workhouse as a tramp,” the man professed, “I would have laughed at the person who told me as one of the imagination of a poet.”[10]

Not long after being banished to Ward’s Island insane asylum, the general was seeking a way to escape. Reports even surfaced that he had died while incarcerated in the gloomy penitentiary. On May 22, 1886, Dr. Stephen Smith, Commissioner of Lunacy of the State of New York, gave his assessment of Egan’s condition when asked if the general was fit to be released:

I have known Gen. Egan for some time, and have often examined as to his condition in asylum, and the propriety of his discharge. Those who have him in charge regard his disease as softening of the brain, of slow progress, but of such character as to incapacitate him to take care of himself. He talks well, though extravagantly, appears very well, and is allowed much liberty. I have recently had a conversation with Dr. C.S. Hoyt [Charles S. Hoyt], an Army Surgeon, who takes great interest in the General, in regard to the propriety of giving him a trial out of the asylum, but he discourages such action, being of the opinion that though he appears so well in asylum he would be made much worse if subjected to the excitement of life outside. It is the opinion of his medical attendants that the slow progress of his disease his due to the quiet of asylum life. I should be very glad to do anything to aid the General to obtain a discharge if that were the best course to take, but under the circumstances I can but regard his residence in the asylum as the most favorable to his health and happiness.

Despite Smith’s disapproval, on June 5, 1886, at a special term of the Supreme Court of the State of New York, Judge Charles D. Donohue ordered Egan discharged from Ward’s Island after receiving a petition from his few remaining friends advocating his release.[11]

To aid the impoverished veteran, a Republican New York senator and former brigadier general during the war, Charles H. Van Wyck, introduced a bill to the Committee on Pensions to increase Egan’s pension from $30 to $100 per month. Dr. J. E. Dexter, the former medical inspector for the III Corps during the war, wrote on behalf of Egan’s case. “I can state that his condition is unqualifiedly deplorable, requiring the attendance of another person, or a physician,” Dexter noted, “all the result of wounds received and exposure incident to his military life.” The committee determined that Egan was unfit to provide for himself and the bill was approved.[12]

In what very well may be his last letter, Egan wrote to his niece, Mary A. Egan, living with his mother in La Crosse, Wisconsin, on December 27, 1886. His handwriting is noticeably distressed in this letter. He began by hoping that Mary had a pleasant Christmas and expressing his desire to visit her before New Year’s Day. At that time, he was down with a cold and waiting for his doctor’s approval to leave New York. It is unlikely that Egan ever made the trip.[13]

On February 24, 1887, at 10:00 p.m., Egan suffered an epileptic seizure and collapsed outside the entrance of the International Hotel. A doctor attempted to administer some brandy to help him regain consciousness but was unsuccessful. Egan was moved to the House of Relief or Chambers Street Hospital, an institution that offered free medical aid to the poor, and passed away that afternoon at the age of 53 years old.[14]

None of Egan’s family members came forward to provide for the cost of his funeral or interment. Members of the Grand Army of the Republic stepped in to cover the expense of both rather than to see the general buried unceremoniously in a potter’s field. The veterans of the 40th New York purchased a fine granite monument and placed it over his grave at the Cypress Hills Cemetery.[15]

It is necessary to consider how lingering wounds and psychological trauma adversely affected the lives of countless Civil War veterans. In looking at sadness and suicide among Civil War soldiers, Dr. R. Gregory Lande fittingly noted “The bullets and bombs stopped in 1865, but the social shockwaves were just beginning.” As General Egan demonstrated, many disabled veterans endured decades of poverty, chronic pain, and emotional distress long after the guns fell silent.[16]

Endnotes

[1] Reports of Committees of the Senate of the United States for the First Session of the Forty-Ninth Congress, 1885-86 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1886), 4-5.

[2] Jack D. Welsh, Medical Histories of Union Generals (Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 2005), 107-108; Frederick C. Floyd, History of the Fortieth (Mozart) Regiment, New York Volunteers: Which was Composed of Four Companies from New York, Four Companies from Massachusetts, and Two Companies from Pennsylvania (Boston: F. H. Gilson Company, 1909), 33; Reports of Committees of the Senate, 5-8.

[3] Reports of Committees of the Senate, 10.

[4] Welsh, Medical Histories, 108; Floyd, History of the Fortieth, 33; Reports of Committees of the Senate, 2.

[5] John Y. Simon, ed., The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant: August 16-November 15, 1864, September 2, 1864, vol. 12 (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1984), 436.

[6] Welsh, Medical Histories, 108; Reports of Committees of the Senate, 1-3.

[7] Norma Basch, Framing American Divorce: From the Revolutionary Generation to the Victorians (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), 129-130; Harrison G. Fiske, ed., The New York Mirror Annual and Directory of the Theatrical Profession for 1888 (New York: New York Mirror, 1888), 123; Michael B. Frank and Harriet Elinor Smith, eds., Mark Twain’s Letters, 1874-1875, vol. 6 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002), 355.

[8] “General Egan’s Complaint,” New York Daily Tribune, July 24, 1883; The Rock Island Argus, July 27, 1883.

[9] Shelbina Democrat, June 16, 1884; “Down Fame’s Ladder,” The Christian Union, July 24, 1884; “Sad Downfall of A Man Who Fought in the Battle of Gettysburg,” The Official Organ, July 1884; Sacramento Daily Record-Union, July 7, 1884; “General Tom Egan, A Once Brilliant Soldier, Sentenced as a New York Tramp—A Sad Story,” The Wheeling Daily Intelligencer, July 18, 1884.

[10] “General Tom Egan, A Once Brilliant Soldier, Sentenced as a New York Tramp—A Sad Story”; Sacramento Daily Record-Union, July 7, 1884; Daily Los Angeles Herald, July 11, 1884.

[11] The Herald, April 17, 1885; The City Record, May 14, 1885; The Military History of Gen’l Thomas W. Egan, John Page Nicholson Papers and Civil War Collection, 1861-1921, The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens, San Marino, California.

[12]The McCook Tribune, June 24, 1886; Reports of Committees of the Senate, 1.

[13] Thomas W. Egan to Mary A. Egan, December 27, 1886, John Page Nicholson Papers and Civil War Collection, 1861-1921, Box 17, The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens, San Marino, California.

[14] The New York Times, February, 25, 1887; “Dangerous Illness of General Egan,” New-York Daily Tribune, February 24, 1887; Alexandria Gazette and Virginia Advertiser, February 25, 1887; “Death of Gen. Egan,” Helena Weekly Herald, March 3, 1887; The National Tribune, March 10, 1887.

[15] Welsh, Medical Histories, 108; Floyd, History of the Fortieth, 33; “Death of Gen. Egan,” Helena Weekly Herald, March 3, 1887.

[16] R. Gregory Lande, Psychological Consequences of the American Civil War (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2017), 24; Sarah Handley-Cousins, “‘Wrestling at the Gates of Death’: Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain and Nonvisible Disability in the Post-Civil War North,” The Journal of the Civil War Era, 6, no. 2 (June 2016): 220-242; Judith Andersen, “‘Haunted Minds’: The Impact of Combat Exposure on the Mental and Physical Health of Civil War Veterans,” in Years of Suffering and Change: Modern Perspectives on Civil War Medicine, eds. James M. Schmidt and Guy R. Hasegawa (Roseville, MN: Edinborough Press, 2009): 143-158.

Tragic story!

This is one of the best biographical pieces on lesser known US generals that I have read in a long time. Kudos to the author!! Excellent research and use of primary sources! I am impressed!

Egan is one of my favorite subordinate commanders in the Army of the Potomac who was promoted up to division command based solely on merit. He was one of Hancock’s best combat commanders. Arguably, Egan’s best day during the war was October 27, 1864 at the Battle of Boydton Plank Road when Egan’s division was surrounded on all sides and he literally had to fight his way out — and did! Hampton Newsome’s excellent book Richmond Must Fall covers this action.

Egan should have remained in the Regular Army after the war, where he would have excelled and maybe stayed out of trouble. Egan’s postwar life was always a mystery to me until now. Thank you for this.

You should use your research skills to uncover the postwar life of General Francis J. Herron–a brigadier general at age 25–who died forgotten and penniless in a NYC tenement house in 1902.

Thank you for the kind words, Todd! I was happy to share Egan’s experiences.

It’s funny that you mentioned Herron. He has been on my radar. I have a list of a dozen or so generals who either perished as a result of their wounds after the war, suffered from long-term disability, or died in obscurity. I would like to write some more posts about these generals. I will have to see what I can uncover about Herron. Thank you for the recommendation.

Glad that you enjoyed the post.

Thanks for your reply Frank. You have an impressive body of work. I have read a number of your articles over the years, but didn’t realize that you were the author of the pieces. Recently, I very much enjoyed your article on the Gibbon/Owen relationship.

I think Herron is such a tragic figure — he peaks early as one of the youngest generals during the war, later holds some prominent positions in the Deep South during Reconstruction, and then disappears from public record, dying alone and poor in NYC.

I would add General Byron R. Pierce–wounded four times–who died in obscurity at age 95 in 1924, but not a tragic figure like Egan or Herron.

Lastly, I put my vote in for General Eli Long, one of the most accomplished cavalry officers to come out of the war. His war record makes Custer look like a slacker. A southerner born in Kentucky in 1837, fought for the Union, became a general at age 27, commanded a division in Wilson’s Raid, and was wounded at least five times, including a nasty head wound at Selma in April 1865. He retired as a brigadier general in 1867 and lived the remainder of his life in quiet obscurity in suburban New Jersey until his death in 1903. What did he do for 36 years?

Thank you! I’m glad you enjoyed the Gibbon/Owen article. I was shocked to discover Owen was relieved on the eve of Gettysburg and missed leading his brigade during this monumental battle. I had to share the tale behind why.

I’ll definitely add Pierce and Long to my list. I’ll have to see if I can get access to their pension files. Maybe this will make a good blog series? If you have any more recommendations feel free to shoot them my way.

Would there be a biography of Egan? Article is brilliant and like a great article leaves me wanting to learn more!

Hi Kevin, and thank you! Not that I am aware of. It took quite a bit of detective work to piece together Egan’s life after the war. Unfortunately, this is the case for many other Civil War generals.

Ah ok. Thank you. It was a fascinating article. Well done!

Great article frank. Lots of good information. Really enjoyed it.

If you ever do a book on these General’s I will be in line to get one. Thanks so much for your hard research and inspiring writing!

I am pretty sure there’s more to the story of Tom Egan and Marie Gordon (depends who you believe); Egan got her pregnant, then afterwards was forced to marry her (only after being beaten by a male friend of Gordon). A boy was born in 1865, but I doubt Egan ever saw the child. I read Egan’s court transcripts in the NYC Hall of Records; his son ended up in Sing Sing prison; for what crime, I can’t remember. Marie Gordon is buried not far from where I live.

It seems probable in my family’s case that the deterioration of my great grandfather not only impacted his life but continued generations afterward right down to me.