Willie Preston: “Who Thinks of Victory Now?”

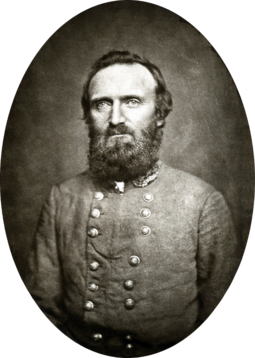

He was nineteen. Full of life. Full of ideas of soldiering. He left Lexington, Virginia, joining up with the Fourth Virginia Infantry and soldiering with other friends from his home town. Before long though, he was anxious to secure a place on “Stonewall” Jackson’s staff and eagerly accepted the general’s offer to stay at headquarters during three summer weeks of 1862.

Willie Preston. His arrival at headquarters pleased Jackson. After-all, he had watched the boy grow up since they shared the same hometown in the decade prior to the war. Jackson may have thought of young Willie as a nephew; they technically were related by marriage. Jackson had married Elinor Junkin. Elinor’s sister – Jackson’s sister-in-law – had married Colonel John T. L. Preston and become stepmother to Willie and his young siblings. With a close friendship with his sister-in-law and Colonel Preston, Jackson knew Willie prior to the war and taught him in a Sunday school class. When the young man with officer aspirations arrived at headquarters, staff officers noted a familiarity between the two and how the general “did his best to make him feel at home and at his ease.”[i]

During the battle of Cedar Mountain, Willie – who originally served in the Fourth Virginia Infantry, Stonewall Brigade – had been separated from the unit, but found and rallied other Confederates, eventually emptying his own cartridge box in a fire fight and capturing at least one Union soldier.[ii] His first battle had been a success, and General Jackson knew of his actions in the fight. At one point during the combat, Jackson found Preston frustrated that he could not find anyone else to go with him to scout the front of that area. Willie – suddenly relieved to see an older, reliable figure – ran over to Jackson and “slapped him on the leg” then “slapped his horse so hard that he came near jumping from during the rider.” (To his father, Willie excused his behavior, saying, “some allowance must be made for me, as it was the first time I had ever been under fire.”)[iii]

Explaining the situation, Willie got Jackson to help find scouting volunteers. With the general moving toward the unit’s position, Willie ran ahead to announce their leader’s arrival “and I thought the heavens would have been rent with the cheers.”[iv] Later, Jackson recalled that the whole regiment then wanted to volunteer.

Former friendships or even kinship had little to do with Jackson’s selection of staff officers. Consistently through his months at war, Jackson chose men that he thought were capable for positions on his staff. Although he struggled to find a chief of staff/adjutant, he rarely misappointed his other staff officers. Crutchfield worked miracles as chief of artillery. McGuire pushed medical boundaries with his hospital, evacuation, and military medicine precedents. Harman fought and argued with “Stonewall,” but ultimately wrangled the supply wagons to their destinations with remarkable efficiency. Pendleton kept watch on the entire command and its paperwork, basically doing the work of chief of staff, but not receiving that title under Jackson. Hotchkiss made maps with accuracy and the needful artistic ability. And there were others who served, and still more who would join Jackson’s staff. It seems by summer 1862, Jackson was looking for a couple of young men to serve as his aides-de-camp; if Willie “fit in” with the staff and was trustworthy, his place and a promotion might be secured.

The new arrival made friends quickly with Jackson’s staff who welcomed his good manners and “became much attached to the boy.”[v] The general later revealed that he intended to appoint Willie Preston as an aide-de-camp, but nothing had been formalized by the end of August 1862.

On August 28, Jackson’s command engaged at Brawner’s Farm in the opening day of the Second Battle of Manassas. Sometime during the fighting that day, Willie Preston fell mortally wounded. Carried off the battlefield, Willie was brought to a field hospital, and Dr. Hunter McGuire examined his injuries. Lacking details, the best medical conclusion from the currently available primary sources suggest that Willie did not endure an operation and that McGuire determined on a type of palliative care for the young man’s final hours.

At some point – probably in the evening – Captain Hugh A. White of the Fourth Virginia Regiment came to see Willie in the field hospital. Both young men hailed from Lexington and had grown up together, though Hugh was older. Willie gave verbal messages to Hugh, who promised to write them down and send them to Willie’s family as soon as possible. It is probably that Hugh also offered prayer or some other spiritual comfort to Willie since they had both attended the same church and were both known for their religious faith.

Dr. McGuire had the responsibility of reporting casualties to Jackson after a day of battle. Leaving Willie, he went to headquarters and started the painful duty. He started by gently informing the general that Willie Preston lay mortally wounded: “The General’s face was a study. The muscles were twitching convulsively and his eyes were all aglow. He gripped me by the shoulder till it hurt me and in a savage, threatening manner asked why I had left the boy. In a few seconds he recovered himself and turned and walked off into the woods alone. He soon came back, however and I continued my report of the wounded and the dead.”[vi]

Sometime in the night, the teenager took his final breaths, and his death plunged his family into grief. It was hard for them to find closure. The messages Willie had imparted to Hugh White were never written down or never found. Captain White died in the battle the following day, leaving Willie’s final words of love to his step-mother, father, and siblings unknown.

Colonel Preston – Willie’s father – journeyed to the battlefield area, searching for his son’s body. Unable to find more than a monogramed shirt to identify his boy, Colonel Preston had two identical grave stones made. One he placed in a field where his son might have been buried. The other he brought to Lexington and erected in the family’s cemetery plot.

Willie’s death had shocked and saddened his uncle by marriage, Thomas J. Jackson. One of the rare times Jackson showed emotion during the war was when he heard the nears about Willie’s sufferings and impending death. Later, Jackson wrote to Margaret Preston, his sister-in-law: “I deeply sympathize with you all in the death of dear Willie. He was in my first Sabbath school class where I became attached to him when he was a little boy. I had expected to have him as one of my aid de camps but God in his providence has ordered otherwise. Remember me very kindly to Col. Preston & all the family. Affectionately your brother, T. J. Jackson”[vii]

Margaret – Willie’s stepmother – wrote in her journal: “I did not know how I loved the dear boy. My heart is wrung with grief….My eyes ache with weeping.” A few days later, she wrote again: “Who thinks of or cares for victory now!”[viii] She tried to express her grief and feelings in poetry, perhaps trying to imagine and make sense of Willie’s final hours.

Break, my heart, and ease this pain –

Cease to throb, thou tortured brain;

Let me die, – since he is slain,

Slain in battle!

Not a pillow for his head –

Not a hand to smooth his bed –

Not one tender parting said,

Slain in battle!

Straightway from that bloody sod,

Where the trampling horsemen trod –

Lifted to the arms of God;

Slain in battle.[ix]

The Preston Family was not the only family to lose a son “slain in battle” on that hot August day. But in the history of Lexington, Virginia, and its families and in the biographical understanding of “Stonewall” Jackson, Willie’s death has added significance.

For his immediate family, Willie’s fall marked the second casualty loss his family endured in less than six months. His older brother, Frank, had been severely wounded, lost an arm, but would ultimately recover. The Prestons – a prominent family in Lexington – shared their losses with their community in the town and church, trying to make sense of the maimed and dead, trying to determine if these sacrifices were worth the price for their Southern cause.

Looking at primary sources about Jackson and Willie’s relationship in the weeks just prior to Second Manassas suggests a familial closeness. They were related by marriage, and Jackson had known Willie for at least ten years, watching him grow up. Was Willie like a son Jackson never had? Although it can be difficult to judge the exact degree of their relationship, it is clear that “Stonewall” cared deeply for young Willie. Grief at the sudden news startled Jackson into anger and probably a weeping sadness that he hid from his staff. Jackson was no stranger to grief; he had lost his parents, his first wife, and several infant children. He had had other friends or acquaintance die already during the war, but Willie’s death emotional punched Jackson, reminding him of the cost of victories. It did not alter “Stonewall” as a fighter. It did not change him on the battlefield. But it is probably safe to suggest that while the general regained his rigid composure externally, the internal memory of his young kinsman and the grief of his sister-in-law and her husband stayed with him.

Willie Preston. His life was short. His battlefield courage at Cedar Mountain was noticeable. His temperament quickly earned him friends. His sudden death at Second Manassas plunged his family into deep grief and mourning, though they all expressed their emotions in different ways. Willie Preston was one of 22,000 casualties from that battlefield, but his life serves as a reminder of the futures cut short through the curse of war.

Note: Sources vary on Willie Preston’s age. I have decided to use the age from his gravestone (nineteen) since that was engraved at the instruction of his father and seems likely to be accurate.

[i] Krick, Robert. Stonewall Jackson at Cedar Mountain. Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 1990. Page 271.

[ii] Ibid., Page 271.

[iii] Ibid., Page 300.

[iv] Ibid., Page 301.

[v] Ibid., Page 301.

[vi] Shaw, Maurice F. Stonewall Jackson’s Surgeon: Hunter Holmes McGuire. Lynchburg, H.E. Howard, 1993, Page 23.

[vii]Stonewall Jackson to Margaret Preston, August 1862. Virginia Military Institute Archives, online. Accessed August 2019. http://digitalcollections.vmi.edu/cdm/ref/collection/p15821coll4/id/595/

[viii] Klein, Stacy J. Margaret Junkin Preston: Poet of the Confederacy. Columbia, University of South Carolina Press, 2007. Page 48.

[ix] Ibid., Pages 48-49.