A First Maine Artilleryman

Emerging Civil War welcomes Doug Ullman, Jr.

James S. Emerson could not have been pleased with how his army career had ended in 1862. Standing at five feet, six inches, he had been one of the early volunteers, enlisting in the Third Maine Infantry less than two weeks after the firing on Fort Sumter. His regiment fought at the First Battle of Bull Run, but had hardly displayed any heroics. The following summer, just as Robert E. Lee’s army attacked the Federals outside of Richmond, Emerson came down with sunstroke that prevented him from participating in the Seven Days’ battles. He was sent to a general hospital in Washington, DC, in August, then to New York City, still suffering from diarrhea, vertigo, and even epilepsy. Following his discharge in December of 1862, one surgeon speculated that it would take one to two years for Emerson to fully recover.

Arriving home sick, Emerson received anything but a hero’s welcome. In fact, according to someone close to him, Emerson’s wife, Lydia, refused to see him and swore to never live with him again. What impact this had on James is unrecorded. However, on January 5, 1864, Emerson enlisted in the First Maine Heavy Artillery.

Like many heavy artillery regiments, the First Maine occupied the defenses of Washington since the earliest days of its service in 1862. In spite of their artillery designation, these men were also trained to operate as infantry, and the war effort eventually needed them in just that capacity. After more than five months of this relative inactivity, Gen. Ulysses S. Grant called for 10,000 of these troops to join the Army of the Potomac, which had been severely bloodied in its weeks of constant combat with Gen. Robert E. Lee’s army. Though they lacked combat experience, the massive size of the heavy artillery regiments—some mustered as many as 1,800 men—would offset their other deficiencies. If Emerson regretted his less than active military career, he would soon have the chance to remedy that situation.

Emerson got his reintroduction to combat on May 19, 1864, when the First Maine and several other heavy artillery regiments met Gen. Richard Ewell’s Confederate corps on the Harris Farm, near Spotsylvania. Lt. Horace Shaw remembered the “vigorous attack…and the stubborn tenacity with which the ‘raw troops,’ as we were called, held on to their ground against Ewell’s whole corps gave the Confederates sudden check and forced them back.” Though often overlooked by historians, the Battle of Harris Farm made a big impression on the Mainers, who lost 579 in the action.

Nearly a month passed before Emerson and his comrades saw serious action again. In the interim, the heavy artillery regiments were distributed amongst the other brigades of the Army of the Potomac. A few took park in the bloody repulse at Cold Harbor on June 3. (By sheer chance, Emerson’s brigade was kept out of that assault.) Following the defeat, Grant still determined to make his way south, this time by assaulting Petersburg, just below Richmond. With Petersburg and its vital railroads in Federal hands, Richmond would fall. However, delays on the Union side had afforded the Confederates ample time to strengthen their defenses and more than enough opportunity to shift troops to meet the threat.

James Emerson probably knew little of this on June 18, 1864, when the 850 men of the First Maine Heavy Artillery formed a line of battle in Prince George Courthouse Road. The Confederate line, bristling with abatis, loomed some five hundred yards ahead. Their regiment—easily the largest in the brigade—was “designated as the center of the storming column.” Its three battalions formed in three lines. The first line’s objective was to clear the obstructions in front of the Confederate works and reach the ditch at the foot of the parapet. The second line would follow, providing covering fire for the men of the first line, then rush in once the obstacles were clear. The third line, Emerson’s likely post, would add its weight to the final push to seize the Rebel line. Their entire division was to advance simultaneously in support. The undertaking seemed impossible to Lieutenant Shaw and many others, “but the First Maine officers and men were soldiers. The first duty of a soldier is obedience to orders.”

At the signal, Emerson and his comrades stepped off with vigor. The other regiments of the brigade—veterans of Fredericksburg, Gettysburg, and the month of battles leading up to that day—advanced too, but intense enemy fire sent them back to the shelter of the road. With their supports running for cover, the Mainers—still advancing amidst the tempest of lead—became the focus of Rebel musketry and artillery. “The earth was literally torn up with iron and lead,” wrote Shaw. “The field became a burning seething, crashing, hissing hell…So in ten minutes those who were not slaughtered had returned to the road or were lying prostrate upon that awful field of carnage.”

Among the prostrate was James Emerson, who had fallen with wounds to the left arm, right thigh, chest, penis, testicles, and buttocks. He was fortunate enough to be brought off the field alive; his arm was amputated at a field hospital the following day. He was subsequently sent to Campbell Hospital in Washington City where his other wounds were treated and additional amputations made. None of these measures were successful, however, and James S. Emerson died on June 30, 1864, at the age of 30.

James Emerson is buried in Section 13 of Arlington National Cemetery. His grave marker lists his date of death as June 18, 1864, the day he received his fatal wounds at Petersburg.

Doug Ullman, Jr. has written numerous pieces for America Battlefield Trust and frequently contributed to their Civil War in4 and War Department series. He is a graduate of New York University’s Steinhardt School.

Sources:

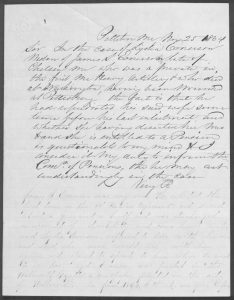

James S. Emerson Pension File, WC #37846, National Archives Building, Washington, DC; Shaw, Horace, The First Maine Heavy Artillery

I wonder if that satisfied his lovely and understanding spouse.