“But his soul goes marching on.” Brown, Douglass, and the Radicals

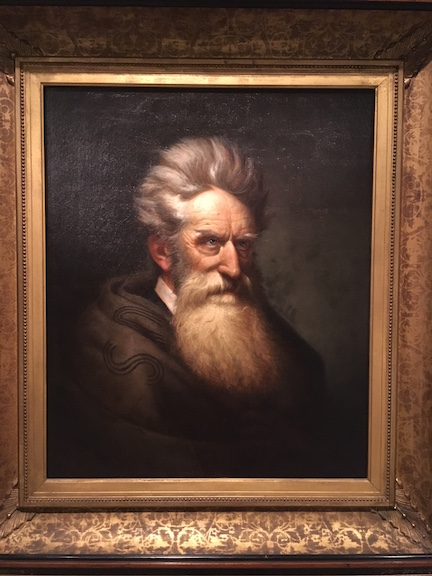

Today abolitionism is praised with few reservations, but it was a fringe movement in the 1830s. Its followers took a lonely moral stand. William Lloyd Garrison in 1831 declared “I am in earnest. I will not equivocate – I will not excuse – I will not retreat a single inch – AND I WILL BE HEARD!” John Brown in 1839 said “Here, before God, in the presence of these witnesses, from this time, I consecrate my life to the destruction of slavery!” These were not men for compromise, and increasingly nor was the emerging ideology in the South that saw slavery not as a necessary evil but instead a “positive good” in the words of John C. Calhoun.

Today abolitionism is praised with few reservations, but it was a fringe movement in the 1830s. Its followers took a lonely moral stand. William Lloyd Garrison in 1831 declared “I am in earnest. I will not equivocate – I will not excuse – I will not retreat a single inch – AND I WILL BE HEARD!” John Brown in 1839 said “Here, before God, in the presence of these witnesses, from this time, I consecrate my life to the destruction of slavery!” These were not men for compromise, and increasingly nor was the emerging ideology in the South that saw slavery not as a necessary evil but instead a “positive good” in the words of John C. Calhoun.

Over time, these fringe beliefs became more widespread. They had both considerable financial backing and eloquent proponents. At the same time, both sections became suspicious of each other. Even if one did not care about freeing slaves, Northerners had a general dislike for the aristocrats of the antebellum South and their disproportionate control of national politics, while any Southern could see the North was growing in political and economic power. Added to the mix was America itself, forged in rebellion over a defense of an Englishman’s rights that was then wrapped in an emerging egalitarian rhetoric. The strain of abolitionism that would eventually destroy slavery was also born of the radical energy created in the Second Great Awakening, a religious revival that embraced social reform and experimentation. In this age experiments in free love, animal rights, vegetarianism, and prohibition were undertaken alongside reforms to prisons, mental wards, and schools. The glue connecting them all was general opposition to slavery. To make the situation more volatile, James Madison had conceived of a government where change was possible but slow. It was a system designed to subvert majority will. To remove any of these ingredients might have avoided the American Civil War, and yet the combination needed a spark to unleash violence.

There is a romance of revolution, where people rise up all at once, almost naturally. You can see it the film and graphic novel V for Vendetta or in movies such as Joker and Equilibrium. It is however false. Rebellions are successful only with an organized group that has agitated for years and can exploit systemic failure. Only weak regimes fall to revolution. None of those works of fiction show that, and indeed the rebellions are sparked by a lone figure who has silent support before the rebellion. Yet, without an overt support network, such acts of violence are at best symbolism and at worst deemed as pure murder. It is why we recall John Brown but have forgotten about Francisco Martin Duran.

John Brown, while a romantic of sorts, had such support, but eventually concluded that most abolitionists were “…all talk. What we need is action—action!” Never one for half-measures (he believed in harsh punishment in the home and the world) Brown murdered men in Kansas, fled the state, and decided to lead a slave insurrection. Missouri placed a bounty on his head of $3,000 and James Buchanan added a $250 bounty. Brown placed a bounty of $2.50 on Buchanan. In the meantime, Brown studied fortifications and military theory and thought a guerilla war would destroy the slave system. Harper’s Ferry, Virginia was chosen as the target not just because of the armory but also the mountains nearby where Brown and his army could hide.

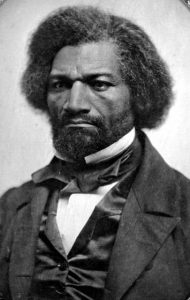

When John Brown planned his insurrection he looked for aid from Frederick Douglass, the escaped slave who became one the era’s most eloquent speakers and fighters of slavery. The two men admired each other, with Douglass musing that Brown felt “…as though his own soul had been pierced with the iron of slavery.” Brown considered his first meeting with Douglass in 1847 to be a high point of his life. Yet, Douglass opposed the plan, thinking it would end with slaves finding it harder to escape and bringing condemnation down upon the abolitionist movement. Douglass also thought Brown would die, but that was seemingly part of the plan. Brown decided that his martyrdom would cause a firestorm and “it seemed to him that something startling was just what the nation needed.” Douglass did not agree, but his friend Shields Green, a runaway slave, joined Brown after the meeting.

In one regard Douglass did support Brown. He told no one who could stop Brown about the attack. Despite his reservations he would not prevent it, for in his heart of hearts he wanted it to work. However, Brown had no more enthusiastic supporter than the Unitarian minister Thomas Wentworth Higginson. He was a radical abolitionist and had taken a saber cut trying to save Anthony Burns before he could be returned to South Carolina. He believed that slavery must be opposed even if it meant ripping the country in two. He was as much for disunion as Alabama Fire-eater William Yancey. If Garrison and Calhoun were the fathers of two opposing camps, their direct children were Higginson and Yancey respectively.

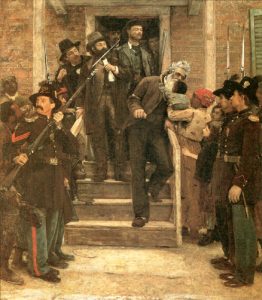

As it stands, Brown’s insurrection was a bungled mess, so ineptly carried out that Garrison called it “a desperate self-sacrifice for the purpose of giving an earthquake shock to the slave system, and thus hastening the day for a universal catastrophe.” Salmon Brown thought his father did it to bring on the war. As Brown himself wrote in 1851 “The trial for life of one bold and to some extent successful man, for defending his rights in good earnest, would arouse more sympathy throughout the nation than the accumulated wrongs and suffering of more than three millions of our submissive colored population.” It is telling that Brown spent a lot of his time in Harper’s Ferry trying to convince his hostages that his cause was just. Once in jail he spoke often, loudly, and directly. He also dissuaded others from rescuing him from jail. He chose death and martyrdom.

Despite Douglass’ fears, the attack did not cause a mass demonization of the abolitionist movement. While it is true many condemned Brown, it was often done with a qualification Abraham Lincoln called him insane, and noted that precious few slaves joined his revolt (possibly because the first man to die in the rebellion was the free man of color Heyward Sheppard). Yet, Lincoln ultimately considered Brown wrong not in his motives but in his means. Such caveats are how radicals now and then exploit moderates. Yancey and the Fire-eaters did similar work in the South, where some did not think secession was not the correct response to Lincoln’s election, but thought it was a God-given right. So, if the state left they would defend it, and Yancey used this when he agitated for secession. Robert E. Lee, who echoed Lincoln by calling Brown “a fanatic or madman,” would be dragged into war by men such as Yancey.

Mixed amidst condemnation of Brown, there were celebrations in the free states. In Albany, New York, a 100-gun salute was fired. Ralph Waldo Emerson compared Brown to Christ and said the former would “make the gallows as glorious as the cross.” Songs and other art were commissioned in his honor. Most tellingly, while his secret backers fled, Higginson held his ground and made no apology. He was not tried and nor were his compatriots. The English political philosopher Robert Filmer once observed that men are not ruled by laws, for ultimately men must decide which laws to enforce and which to ignore. Higginson’s fate certainly bears that out. Brown was tried for treason against Virginia and not the nation. Both were sure signs the country was fracturing rapidly.

After John Brown’s rebellion, the South saw a wave of lynchings, mostly of white men who were known to denounce slavery. Laws were passed making it criminal to even discuss abolition. Incidents of arson in Virginia skyrocketed, leading to renewed fears of another John Brown. Militia units sprouted up and states scrambled to buy weapons. Given the bloodshed of Nat Turner’s rebellion and the Haitian Revolution, the South feared slave rebellions, particularly ones led by white men. Jefferson Davis on the Senate floor said “The great consideration is the invasion of a State to disturb its domestic peace, the preservation of which is a purpose which stands prominent among the great objects for which our Union was formed.” In the South, paranoia, already common given both the system of slavery and the region’s honor culture, reached a fever pitch a year before a presidential election. Lincoln may have lost, but Yancey manipulated events to cause a fatal split in the Democratic Party.

Before he died, Brown said “I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land can never be purged away but with blood.” The war Brown, Higginson, and Yancey wanted came. The peace sought by Lincoln, Lee, and Garrison, failed. Lincoln would plead in his first inaugural address “We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained, it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory will swell when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.” Weeks later P.G.T. Beauregard, who in 1860 declared that secession and civil war were unlikely, fired the first shots at Fort Sumter. The mystic chords had been severed and they have never fully healed since that time.

Brown has remained a figure of controversy, but also of inspiration to radicals of varied stripes, from Antifa to the anti-abortion activists. Yet, his religious zealotry makes him hard to understand for an increasingly unreligious people. He led a failed rebellion and before that hacked men to death with broadswords, neither of which has made him a true popular hero. Yet, he did this against system few would defend today. We feel ambivalence, but at the heart of it is the understanding that in the right circumstances some can condone the murder of our countrymen. Violence is good if it is for righteous ends.

Higginson by contrast draws no such controversy. So much of what Higginson believed in, save prohibition, is fashionable now. The neo-reactionary thinker Curtis Yarvin (writing as Mencius Moldbug) once said of Higginson “you can go to Google and read T. W.’s writing, and observe that for the most part it’s fresh as a daisy and could be read on NPR tomorrow, without shocking or even surprising anyone.” What was once radical is commonplace. In addition, Higginson became an officer in the Union army, commanding black troops and writing about it in a memoir. He also discovered and mentored Emily Dickinson. All of these accomplishiments have received wide praise. While hardly a well-known figure, the only denunciation I have encountered of him is in Yarvin’s essay “Technology, communism and the brown scare.”

Years later, Douglass wrote “John Brown began the war that ended American slavery and made this a free Republic. His zeal in the cause of freedom was infinitely superior to mine. Mine was as the taper light; his was as the burning sun. I could live for the slave; John Brown could die for him.” Brown appeared as a failure in 1859, yet he achieved his goal. A similar man was Osama bin Laden. He could be deemed a failure in 2001, but he stated “The focus must be on actions that contribute to the intent of bleeding the American enemy.” Bin Laden hoped to draw America into costly wars that would drain the country while also creating a breeding ground for radicalism. At this point, who would say Bin Laden did not win? Brown and bin Laden were not madmen, but religious fanatics who believed they could improve the world through violence and force moderates out of their supposed stupor. It is fitting that Union soldiers from abolitionist hotbeds went on campaign in the Civil War singing “John Brown’s body lies a-mouldering in the grave, But his soul goes marching on.”And so it goes on, as fanatics drag moderates along in an endless tale of bloodshed in the service of utopia.

Thoughtful, well written piece. Captures the essence of the dilemma: is John Brown a true Hero, or a fanatic who exemplified, “The Ends justify the Means?”

Thank you Mike, but for me the real dilemma is the truth that moderates are sometimes led by the nose by fanatics, and they go along with it. In math terms, John Brown > Lincoln.

When someone criticizes John Brown as a terrorists for attacking slavery, I ask “what does that make Robert E. Lee for defending slavery?”

Robert E. Lee was killing people in a war, which was legitimized killing. Virginia and the other Confederates states democratically seceded from the Union and therefore rebelled under color of law. It wasn’t just some random acts of violence against people Lee disagreed with.

John Brown killed innocents because they disagreed with him or were conveniently in his way, like the folks in the World Trade towers.

Bob,

I think all Lee and Brown prove is that with the “right” cause or reason we are perfectly willing to murder friends and neighbors to achieve our ends. If we deem the cause moral then they are a hero. If not they are a villain worthy of being hanged.

Robert E. Lee didn’t murder anyone. He killed and mutilated his neighbors in a war.

bin Laden didn’t win for sure. Not a single despotic Arab Muslim country has become an Islamist led theocracy and therefore no worldwide caliphate has been established, which was bin Laden’s lodestar. Tunisia has held, Egypt has held, Iraq has held, Syria has held, and most importantly bin Laden’s most hated enemy the Saudi royal family has held.

We should be very careful in celebrating John Brown, because it justifies killing and violence against innocents, if the believer believes their cause is just enough. Who the hell was he to drag Lincoln and Lee into that?

Fuck John Brown.

In terms of bin Laden, one the front of draining and dividing America, he beat us better than any other opponents save maybe Giap and Ho Chi Minh.

I disagree. bin Laden actually united Americans. Killing him and then standing up to the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria has been a bipartisan affair. We have lost fewer people and defeated extremist Sunni Islamism so far. What were we going to do after 9/11, just turn the other cheek to al Qaeda and violent Islamism? Did we go about it competently? Should we have invaded Iraq to get rid of Saddam Hussein? No, I don’t think we did, but as of to today bin Laden is dead and violent Sunni Islamists aren’t running any country. Bully for us so far.

America’s political divisions are of our own doing, not bin Laden’s.

Bush and Obama both got re-elected throughout the incompetent ordeal. So we were politically stable throughout. I can’t even think of a successful anti-war protest against Bush or Obama. Maybe Trump is what a successful anti-war protest looks like in America. Sui generis like no other.

That’s how to elevate the dialogue here. And we just had a series of posts/comments on this site about attracting younger people to an interest in the Civil War.

Appealing to the “young” is a tricky thing. They are not monolithic. The dirty secret about George Wallace in 1968 was that he did best with people aged 21-29. Meanwhile, millennials drink less than their parents but the wine industry is booming among the young.

As to contemporary matters, I won’t go into them insofar as Brown is a figured admired by people of diverse backgrounds tied by the thread of radicalism and a support for violence. This is not a “right vs. left” thing but a human thing.

I’m just being provocative. People perk up at expletives.

Not always in a positive way. It can actually divert from the point being made.

John Brown only sought to kill people who were pro-slavery; they were not innocent. Where is your pearl clutching when it comes to the brutal treatment of slaves?

Higginson was an interesting character; in some ways the George Soros of his time.

He certainly had diverse interests. His Civil War memoir is among my favorites.

“the cultural hegemony of capital….which the author of course ignores entirely.”

I am not sure if this reply is meant in jest or seriousness so I invoke Poe’s Law.

If by that you mean I should look up “the cultural hegemony of capital” no need to as I am acquainted with the concept (as any reader of Jacobin would be). If something else is intended let me know. If serious, I am curious why you brought up “the cultural hegemony of capital.”

I will take it that your first comment is meant seriously. If this was a “facebook rant” it is odd in that has so many quotations, details, and the unwillingness take a hard political stance. That or maybe the rants I see on facebook are much more vague and low-brow than what you see.

The piece is mostly about how Brown was effective and acting in a tradition of using radical violence to force moderates to act. Brown is admired by people of diverse ideologies. His image is used by antifa, anti-abortion activists of the violent variety cite him as an inspiration, and like bin Laden he was a religious fanatic who hoped his act of violence would bring on a war.

We live in a partisan age, but I assure you this is not a partisan piece.

John Brown hoped his acts would end slavery. The slavers ensured the only way to do so was through war. Brown understood this.

“And so it goes on, as fanatics drag moderates along in an endless tale of bloodshed in the service of utopia.”

That, of course, seems like an apt description of the likes of Edmund Ruffin, et al., in addition to John Brown, doesn’t it. I respect thoughtful analysis – as long as it’s objective and even-handed. ;.

Which is why I brought Yancey repeatedly in the article. It is odd we speak and write so little about him, when he was as important if not more so than Brown in bringing on disunion and war.

If ECW wants to do something on the fire-eaters I have a lot to write about.

True dat. i wasn’t necessarily directing my point at the article but at the general concept. I’d look forward to something on that group.

Thanks John, and sorry if I sounded touchy. Some people misread the post as a partisan piece. maybe that is my writing or just these dreary times.

That alt-right article by Moldbug you referenced actually helps makes the case that Brown and Higginson were right. If people who favor genocidal eugenics programs of “racial inferiors” hate you then clearly you’ve done some good.

But the comparison of “radicals” with bin Laden against “moderates” especially doesn’t fly when you consider we’ve governed by the neoliberal “center” that entire time (and no, Trump is no exception for all his words).